Emotion-Evoking Media

Artificial intelligence can now generate images, narratives, and performances with remarkable aesthetic fluency, but it still lacks the most fundamental ingredient of emotional storytelling: human experience. Unlike human creators, machines have no bodies, memories, sensations, relationships, personal histories, or inner consciousness to draw from. They can analyze and reproduce patterns of emotional expression, but the feeling itself never originates within them.

This gap becomes more apparent in emerging art forms of human-machine collaboration, where a machine’s output may appear expressive on the surface but remains rooted in simulation rather than in the art-making experience. When an AI system produces a “sad” image or a “nostalgic” echo in a poem, the emotional effect stems from aesthetic pattern-matching, rather than a lived moment of loss, joy, longing, or fear. This raises an essential question for the future of creative work: If emotion in art comes from lived experience, what are the limits of machine-made emotion?

For most of human history, art has served as a vessel for a lived experience. From Paleolithic cave paintings to Renaissance altarpieces to contemporary performance art, emotional expression has been inseparable from the human body and psyche. Art has always emerged from a specific context, a memory, a trauma, a joy, a cultural ritual, a political event, a deeply personal relationship with the world. Even the most abstract artistic movements, such as Expressionism or Abstract Expressionism, were built on the premise that internal human states could be externalized through a gesture, color, form, and texture.

This long artistic lineage underscores a simple but profound truth: emotion in art has always been tied to embodied subjectivity. A painting or poem does not feel on our behalf; instead, we feel because we recognize something of ourselves in it. This recognition is grounded in shared human experiences, the same nervous system, the same social instincts, and the same emotional development shaped by memory and culture.

AI disrupts this lineage not because it creates “new” art, but because it creates art without experience. It produces outputs that resemble emotional expression, but without the internal states that historically generated emotional meaning. That tension is at the heart of contemporary debates about authenticity, authorship, and emotional depth in machine-made media.

The central ideological divide in AI-generated art concerns the difference between emotional simulation and emotional experience. A machine can process millions of images tagged with “sadness,” learn their statistical patterns, dark palettes, drooping forms, slowed tempo, and generate something aesthetically similar. However, the machine does not comprehend sadness as a genuine feeling. It only understands sadness as a pattern.

This pattern-learning is precisely what the Stanford ArtEmis project demonstrates. As described in the MuseumNext article How AI Has Learned Human Emotions from Art, researchers trained AI on over 440,000 human descriptions of emotional responses to artworks. The algorithm became remarkably capable of predicting the emotions a viewer might feel when looking at a specific painting, even generating explanations that sound convincingly human.

Yet this emotional intelligence is synthetic. The machine does not arrive at these explanations through introspection, memory, or empathy, but through a probabilistic reconstruction of human emotional language. As the article notes, the result is powerful yet uncanny: AI can articulate emotional meaning without ever having experienced it.

This distinction between feeling and imitating the language of feeling reveals the ideological core of our challenge. If machines lack embodied experience and emotional consciousness, they cannot originate emotional content. They can only reproduce its surface-level signatures.

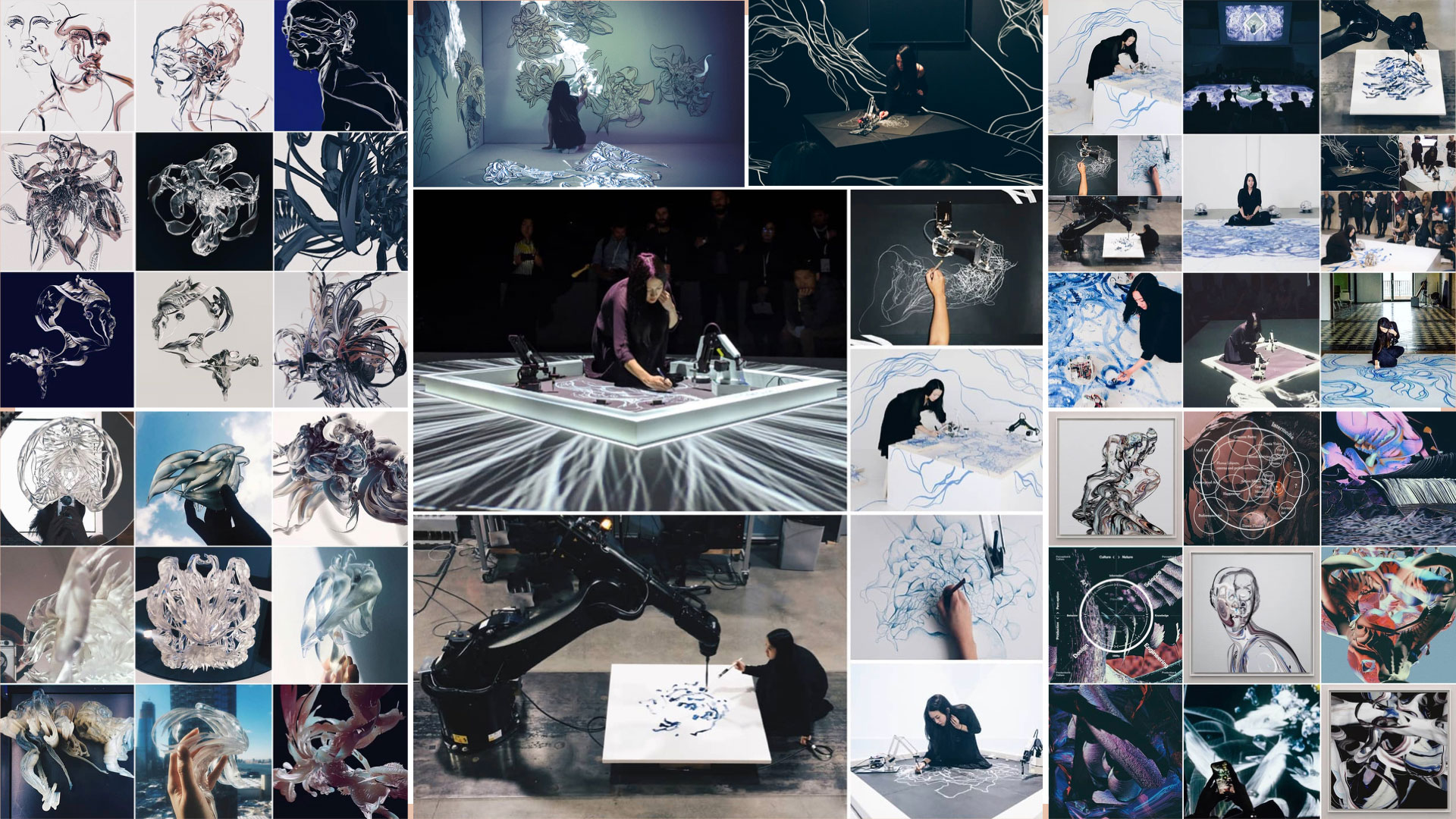

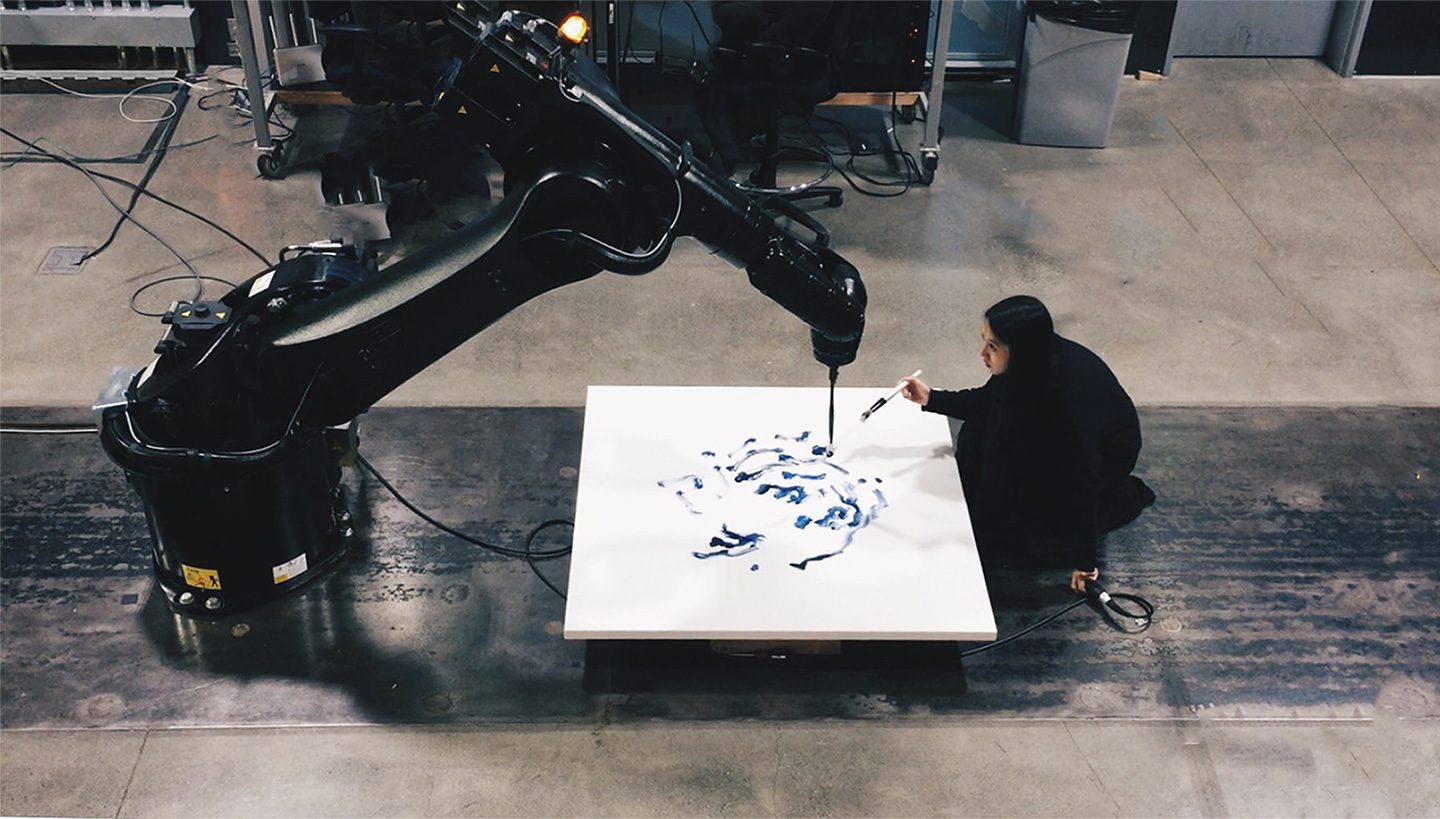

Artist Sougwen Chung’s work makes this distinction visible. Chung collaborates with robotic arms trained on her own drawing gestures, creating hybrid performances where human motion meets machine precision. The emotional resonance of her work emerges not from the machine’s “intent,” but from the dynamic, relational space between artist and algorithm.

The robot does not feel the line, but Chung does. The emotional depth in her pieces stems from her breath, movement, memories of drawing, and the physical tension of performing alongside a system that mirrors her. Chung’s practice demonstrates that machines can extend human expression, but they cannot originate its emotional core.

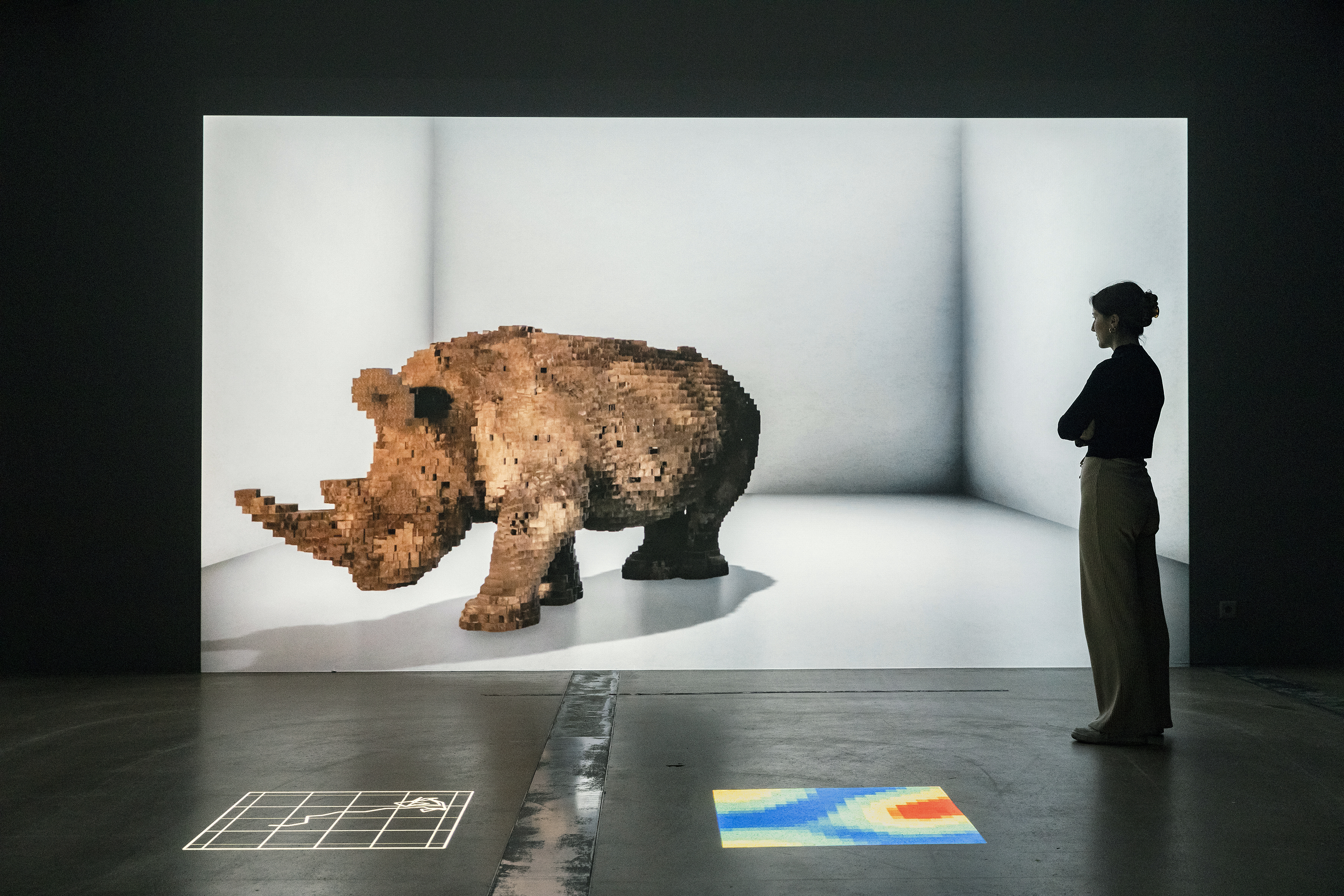

Daisy Ginsberg’s installations take a different approach, using AI to explore themes of ecology, extinction, and environmental grief. Works like Machine Auguries and Pollinator Pathmaker use generative systems to model futures shaped by human environmental impact.

But the emotion in her work, nostalgia for vanished ecosystems, anxiety about the future, mourning for lost species, is entirely human. The AI models do not feel loss. They simply simulate ecological outcomes. Ginsberg’s art relies on human emotional projection, inviting viewers to confront their own fears and hopes. The machine becomes a tool for staging emotional questions, not a source of emotional content.

Refik Anadol’s large-scale immersive works push machine-generated aesthetics to their sensory limits. Installations like Machine Hallucinations or Unsupervised overwhelm viewers with continuously transforming patterns derived from massive datasets. The result is moving, even awe-inducing.

But here again, the emotion resides in the viewer, not the system. The machine produces spectacle swirling patterns, vibrant colors, and algorithmic motion, but not emotional intention. What we feel in front of Anadol’s work is our own psychological response to scale, sound, rhythm, and novelty. The machine amplifies sensation, but not subjective sentiment.

Together, these examples support a clear claim: AI can generate emotional effects, but not emotional sources. Its creative output may provoke awe, melancholy, or wonder, but these emotional responses arise from human interpretation, human memory, and human embodied experience.

AI art is influential not because machines feel, but because humans continue to bring feeling to the encounter.

As AI becomes more integrated into creative practice, the question is not whether machines will replace human emotional expression; they cannot, but how humans will navigate a world where simulated emotion increasingly resembles the real thing. The future of artistic storytelling may depend less on what machines can generate and more on how we choose to interpret, collaborate with, and critically question the emotional simulations they produce.

Authors & Sources

- Authors: Chelsea Cowsert, Rachel Karls, Tucker Christensen, and Callum Robinson

- Tools Used: ChatGPT

- AI Contribution: Text drafted collaboratively with AI and edited by the authors.

- Prompt Log: https://chatgpt.com/share/691bdfcf-2510-8012-aaba-afc72ab37ee5

- Sources & References:

- Sougwen Chung, D.O.U.G._1 (2015)

- Sougwen Chung, D.O.U.G._2 (2017)

- Kate Crawford, Echoes of the Earth (2020)

- Refik Anadol, Machine Hallucination (2020)

- Erin Gee, Swarming Emotional Pianos (2014)

- Daisy Ginsberg, The Substitute (2019)