Prompts: Do Words Matter?

This project investigated how prompt crafting affects AI-generated art through seven structured experiments across multiple image models including ChatGPT, Midjourney, Sora, and others. Each team member tested the same seven research categories—artistic judgment criteria, model performance comparison, misspelling effects, descriptive versus minimal prompts, human versus AI-written prompts, and generating realistic impossibilities—using three different models with 2-3 prompt iterations per category. This controlled methodology allowed us to compare how specific linguistic choices influence visual outputs while revealing each AI system's interpretive tendencies. By analyzing our collective results, we sought to answer a fundamental question: do the words we choose when prompting AI actually matter, and if so, how?

When Marnie asked two AI models to visualize "a cpw jimpung iver the miin," their responses exposed something fundamental about creative collaboration with machines. ChatGPT's generator corrected the garbled text and produced a whimsical illustration of a cow leaping over a smiling crescent moon, complete with stars. But OpenAI Art surrendered to confusion, printing the misspelled prompt directly onto an image of a bewildered sheep character as if to say: I don't understand, so here are your words back. Same incomprehensible input. Opposite interpretations. One model forgave the linguistic mess; the other made its confusion visible. This wasn't a glitch—it was evidence that prompts don't command machines. They negotiate with them.

When Language Breaks Down

Marnie's misspelling experiments revealed the most about how different AIs handle uncertainty. When she tested "Draw a picture of a cow jumping over the moon" versus "draw a picture of a cpw jimpung iver the miin," the results diverged dramatically. ChatGPT auto-corrected the nonsense into a storybook-style illustration with a Holstein cow mid-leap above a personified moon. It demonstrated pattern recognition that transcends literal text—the system inferred meaning from context, like a human reading a typo-filled message and understanding it anyway. But when OpenAI Art encountered the same garbled prompt, it treated the nonsense as literal content, printing "cpw jimpung iver the miin" onto the image as visible text overlaying a cute sheep character. It exposed the brittleness underneath apparent intelligence.

Neither response is wrong. They reveal different training philosophies: one AI learned to be forgiving, interpreting intent through surrounding patterns; the other learned to be literal, treating unclear input as something to display rather than decode. This difference matters because it shows AI doesn't just execute commands—each model has its own relationship to ambiguity, its own interpretive personality.

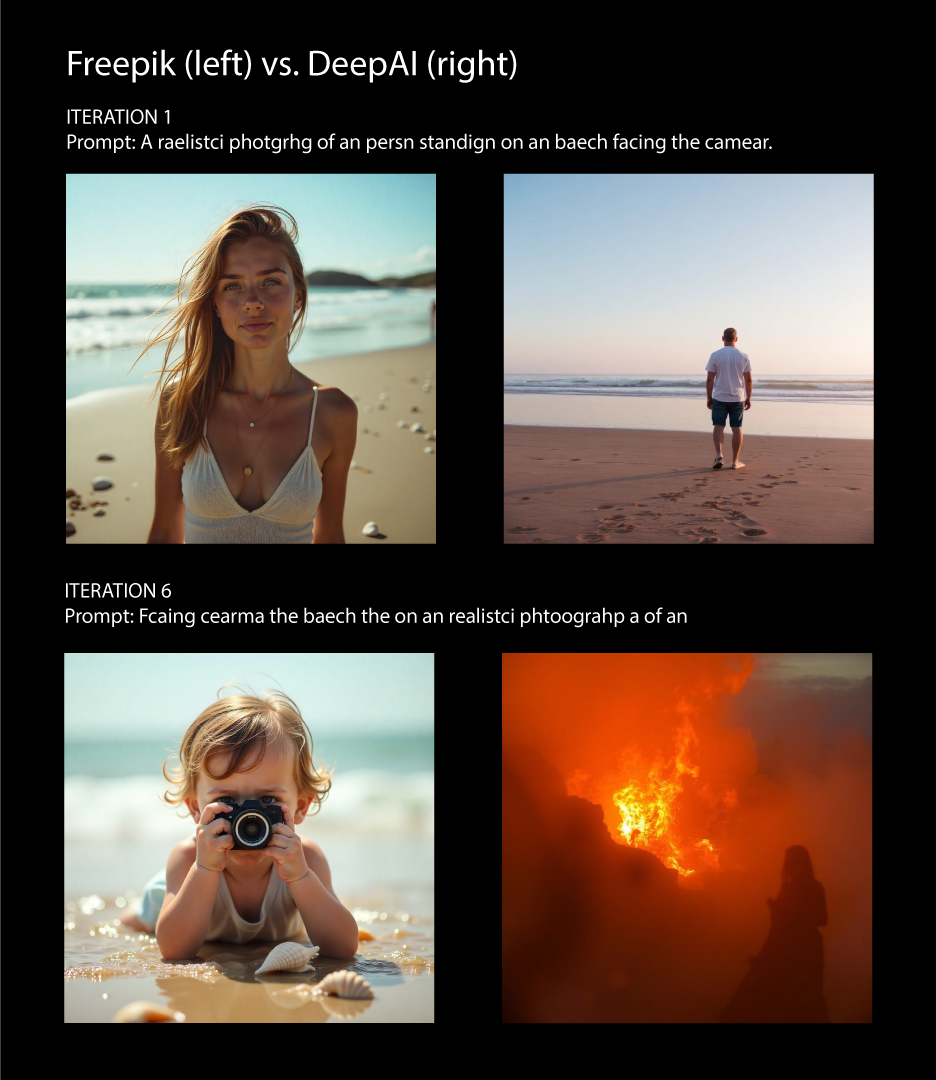

Muni's work on progressive prompt degradation reinforced this pattern. Testing Freepik versus DeepAI with grammar that deteriorated across seven iterations, Muni found that Freepik maintained semantic consistency—continuing to generate realistic beach portraits even as spelling collapsed—while DeepAI drifted into surreal territory, eventually producing a figure in a volcanic landscape. Freepik prioritized what the user meant over what they said. DeepAI responded to the linguistic surface itself, following the text's degradation into stranger visual territory.

What's striking is that both approaches produce meaningful results. Marnie's auto-correcting cow proves machines can parse messy human language. The confused sheep with visible text overlay proves machines will honestly signal when they don't understand. Between these extremes lies the entire challenge of prompt-based art: we're not just learning to write better instructions; we're learning which creative partner we're working with and how that partner handles uncertainty.

Designing the Framework: From Concept to Visual Metaphor

Diego's contribution established the conceptual architecture for our entire investigation. By creating seven distinct "exhibition sites"—each representing one research category—Diego translated abstract questions into concrete visual prompts that all team members could test systematically. The "surreal gallery interior where paintings float in mid-air, each surrounded by glowing rating-orbs" became our framework for investigating artistic judgment. The "futuristic laboratory where multiple AI image models appear as abstract crystalline machines" defined how we'd compare model performances. The "split-screen scene showing two AI interpretation chambers" visualized the misspelling experiments that Marnie and Muni would later execute.

These weren't just test prompts—they were Diego's way of making the research questions themselves into art. The metaphors mattered: portraying different AI models as crystalline machines displaying holographic screens suggests each system has its own material form and unique way of projecting reality. Showing misspellings through split chambers with contrasting visual outputs (clean versus chaotic) perfectly captured what we'd discover: that linguistic errors don't just degrade quality—they reveal which models prioritize correction versus literalism.

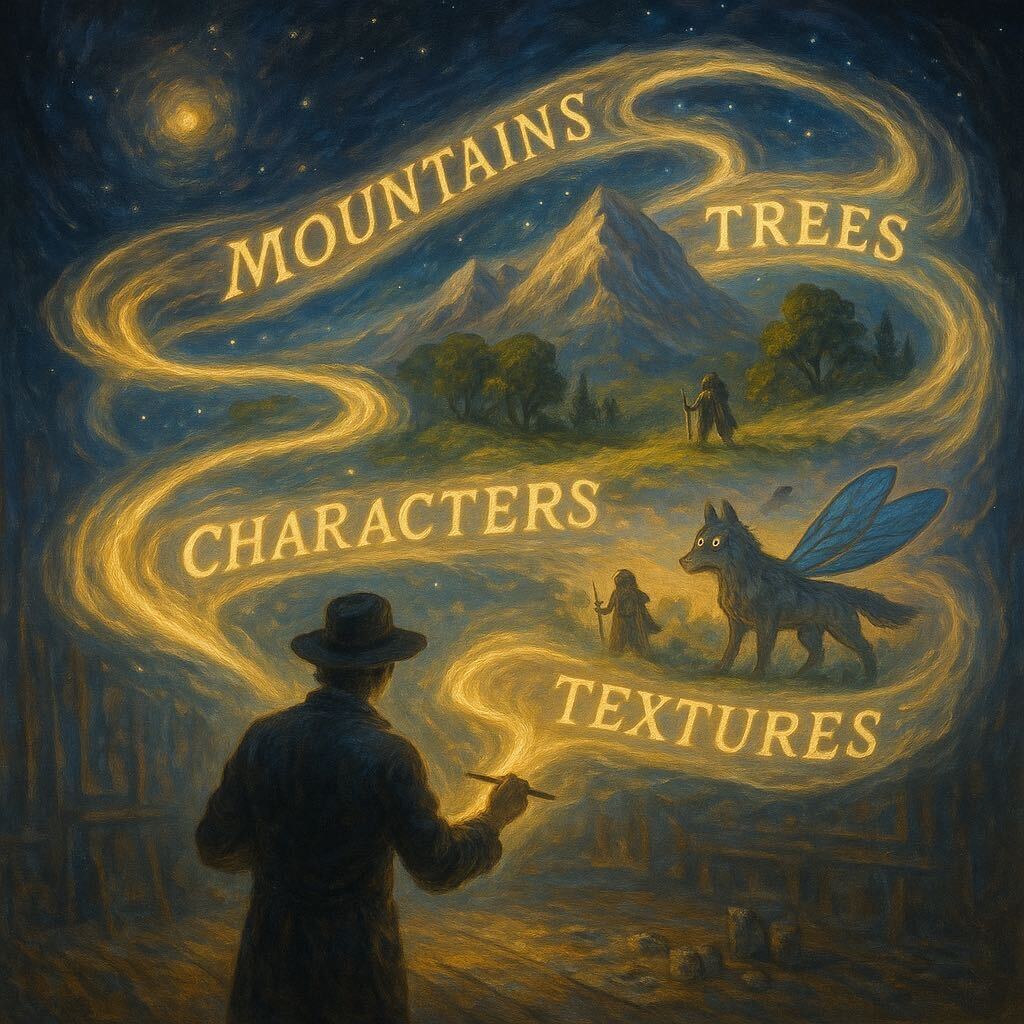

Diego's "cosmic studio" where an artist paints with glowing words that transform into visual elements established the central thesis of our research before we'd even generated our data. Words are the medium. They flow like paint, transform mid-air, build worlds. This visualization predicted what our experiments would prove: that prompt crafting isn't instruction-giving—it's a form of linguistic painting where word choice directly shapes aesthetic outcomes.

Human Intuition vs. Machine Precision

Abbas's comparison of human versus AI-generated prompts exposed another layer of this negotiation. The human-written prompt—"A person standing in a quiet room, holding an old photograph, with sunlight illuminating the dust in the air"—used 19 words to capture a mood. The machine-generated meta-prompt expanded this to 47 words: "A person standing alone in a quiet, empty room, holding an old worn photograph. Sunlight beams through a window, illuminating floating dust in the air. Soft shadows, warm atmospheric lighting, cinematic realism, shallow depth of field, high-detail textures, emotional and nostalgic mood."

Both produced compelling images, but with different emotional registers. The AI's version treated image generation as manufacturing—specifying technical parameters like "shallow depth of field" and "cinematic realism" as if programming a camera. The result was more polished, more obviously professional. The human prompt treated generation as meaning-making, trusting the model to interpret "quiet room" and "sunlight illuminating dust" as atmosphere rather than checklist items. The result felt more intuitive, less engineered.

This validated what Diego's two-portal metaphor suggested: on one side, a dense paragraph of text swirling into a highly detailed complex world; on the other, a short poetic phrase forming a minimalist elegant scene. The contrast between "complex versus subtle" energy proved real in our actual results. AI-written prompts succeed by being exhaustive and technical, while human prompts succeed through suggestion and emotional resonance. Neither is superior—they represent different creative philosophies.

The Interpretive Personalities of AI Models

Dakotta's comparison of ChatGPT versus Gemini using the same poetic prompt—"The Bond That Broke the Stars"—demonstrated that model choice fundamentally shapes aesthetic outcomes. ChatGPT rendered the concept as abstract visual poetry: two silhouetted figures reaching toward each other across a split canvas of ice-blue and molten-orange cosmic forces. Gemini interpreted the same phrase literally, staging a cinematic confrontation between Darth Vader-like figures with glowing energy effects and dramatic lighting. Same words. Radically different visual languages.

This pattern held across all our experiments. Even with identical prompts, models produced distinct results based on their training data, architectural biases, and design priorities. When Diego's prompts were tested across different systems, the "futuristic laboratory with crystalline machines" looked sleek and minimalist in one model, became populated with detailed technicians and equipment in another. The "split-screen AI interpretation chambers" rendered as neon-lit sci-fi in some systems, warm and atmospheric in others. These aren't bugs—they're the models' aesthetic identities.

The implications run deeper than style preferences. These differences show that AI models aren't neutral tools—they're creative agents with their own ways of seeing. When Marnie's correctly spelled "cow jumping over the moon" produced both whimsical storybook art and photorealistic imagery depending on the model, it proved that even clear prompts get interpreted through each system's particular understanding of visual language, tone, and genre.

What This Means for Human Creativity

Throughout our research, one pattern emerged clearly: more detailed prompts don't automatically produce better images. Sometimes minimal prompts yielded surprising creative results because they gave the AI interpretive freedom. Diego's longer, elaborate exhibition prompts produced rich, detailed scenes—but sometimes a simple phrase worked just as powerfully. The skill isn't in writing longer or shorter prompts—it's in calibrating how much control to assert versus how much agency to grant the machine.

This reframes what creativity means when working with AI. We're not being replaced. We're learning a new artistic language where success means effective negotiation with an entity that has its own interpretive logic. When Marnie's misspellings sometimes worked and sometimes produced visible confusion, when Diego's metaphors translated into literal visual elements, when Abbas's minimal prompt carried emotional weight that exceeded its word count—we witnessed distributed authorship. Neither human nor machine is the sole creator. The art emerges from the relationship between human imagination and machine interpretation.

Consider what happened across all seven of our research categories: AIs judged artwork through visual patterns we didn't specify (Diego's glowing rating-orbs became real evaluation criteria), performed differently based on their training philosophies (Dakotta's model comparison), handled linguistic errors in revealing ways (Marnie's misspelling test), transformed poetic language into symbolic imagery (Abbas's human prompts), generated their own prompts with technical precision (Abbas's meta-prompts), and made impossible creatures look utterly believable. In each case, the machine wasn't just following orders—it was interpreting, inferring, choosing based on what it had learned from millions of images.

Conclusion: Words as Creative Negotiation

So do words matter? Yes—but not as precise instructions. They matter as negotiation points in a creative dialogue with entities that have their own interpretive agency, biases, and unexpected solutions. Our experiments show that prompts don't function as blueprints. They function as invitations: we propose a concept, the machine responds with its interpretation, and we iterate based on what emerges. This feedback loop reshapes both parties—humans learn machine-friendly language patterns while machines are trained on human aesthetic preferences.

When ChatGPT corrected Marnie's broken language to generate a cow jumping over the moon, it chose understanding over literalism. When OpenAI Art printed her garbled text onto a confused sheep, it chose honesty over assumption. When Diego's metaphors became literal visual elements—words flowing like ribbons of light, crystalline machines displaying art, portals with contrasting energies—the AIs proved they could translate abstract concepts into concrete imagery. When Abbas's quiet human prompt produced intimate atmosphere and Dakotta's poetic phrase split into dual interpretations, the machines demonstrated they understand suggestion as well as specification.

Both types of results are valid. Both teach us something about the creative relationship we're building with these systems. The cow jumped because one machine chose to understand. The sheep stood bewildered because another chose visibility over correction. The exhibition sites materialized because Diego framed research questions as visual metaphors. The human-written scenes carried emotional weight because Abbas trusted inference over instruction. All these images are artifacts of human-machine entanglement, and all answer our research question: words matter immensely—not because they control AI, but because they initiate collaboration with algorithmic partners whose interpretation will always contain elements of surprise.

In the posthuman age, prompting is the art form, and the negotiation is the point.

Authors & Sources

- Group Members: Abbas Azarm, Dakotta Bhatti, Marnie Cooper, Muniroth Ly, Diego Silan

- Tools Used: ChatGPT Image Generator, Sora, Midjourney, OpenAI Art, Gemini, Freepik, DeepAI

- AI Contribution: Text drafted collaboratively with Claude AI and edited by the authors. All research, experimental design, image generation, and analysis conducted by group members.

- Research Categories:

- 1. How do you judge artwork?

- 2. How do different models perform versus each other?

- 3. How do misspellings and poor grammar affect output?

- 4. "Painting with words" - descriptive prompt crafting

- 5. Prompt length vs. poetic/concise prompts

- 6. Human-crafted vs. machine-crafted prompts (meta-prompts)

- 7. Can AI generate realistic images of things that don't exist?

- Chat Logs:

- https://claude.ai/share/e7e31e1f-16b7-415f-9d99-eb51ad274064

- https://chatgpt.com/share/691beeab-ca34-800a-90e2-bfd512efaa00

- https://chatgpt.com/share/69184a4c-a4b4-8011-88a4-ea79c4e49294

- Methodology: Each team member tested all 7 research categories across 3 different AI models with 2-3 prompt iterations per category, generating 42-63 images per person. Final images were selected through group curation.