Hey everyone, here is my final project. Any feedback is greatly appreciated as I’ve gotten to my ideal point for a final draft, audio tweaking will be my goal for the next week.

Thanks for watching! I’m getting my money’s worth for this Dobby mask.

DTC 208 Introduction to Digital Cinema

Washington State University Vancouver

Hey everyone, here is my final project. Any feedback is greatly appreciated as I’ve gotten to my ideal point for a final draft, audio tweaking will be my goal for the next week.

Thanks for watching! I’m getting my money’s worth for this Dobby mask.

Hey everyone, here’s my version of our one minute short.

Hey everyone,

For my final project, I plan on creating a short film that deals with time traveling. I’d love to incorporate a looping aspect to this short that change as the story continues. The story follows the main character who discovers how to travel through time after a day’s strange events. It turns out that what happened during the day was caused by the main character after they traveled into the past to help themselves that day. It’s a big undertaking story wise, but would be very easy and accessible to shoot for a 2-5 minute short film. I feel that this topic would be a great balance of challenge and achievability. I would include no more than three people in this project if there’s a need for more than the main character, which I have not yet determined. The plot would go as follows:

Character goes through their day and experiences weird events that help them out.

Character stumbles onto a time travel device with their name on a note next to it.

Character goes back and forth in time, then to the future where they met future them. Evil or wise, not sure yet.

Future self tells them to save their past self to continue the cycle.

Goes back and sees that they were the one helping their past self at the beginning.

Cycle continues.

I need to flesh out the story quite a bit more and ensure it makes sense story wise and for how the scenes would be put together. Overall, I’m excited how this project will turn out!

-Caleb

Hey everyone, here is my re-uploaded interview.

Hey everyone,

The challenge for this week is to try and find moments of visual storytelling from the film Devil’s Playground. Keeping in mind the theme of Amish vs. English, I found that most of the visual storytelling came from the physical expressions of the people involved in the story. And this makes sense, as the story pertains to the people and their transition from the Amish style of living to modern English living. This proves to be an effective form of storytelling as the audience can follow the teenagers’ thoughts and feelings about this immensely important decision that affects the rest of their lives.

The first screenshot I found was the same one we used for the module thumbnail in this course and is also the poster for this movie on IMDB. I’d argue and assume this was the reasoning for it being the thumbnail, that this shot perfectly depicts the theme Amish vs. English. An Amish-dressed individual smoking a cigarette, two worlds colliding at one distinct moment. It also uses the person to tell the story and how they interact with their environment.

Velda Bontrager talks about and shows her Amish wedding dress. As we’ve discussed in class, the storytelling isn’t the dress itself or when Velda puts on the dress. The storytelling comes from Velda’s facial expressions, the way she looks at the dress as if in admiration of its beauty, but she later admits that she would never get married or go back to being Amish because of what the dress represents. The audience gathers the story from her expressions in this shot.

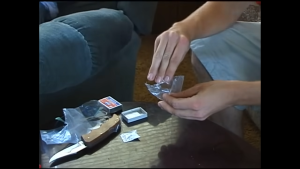

Next, we have a scene that isn’t facial expression but also one that I’m unsure if it’s real or not as I’ve seen documentary style films before that include incriminating evidence of narcotic use and distribution. This is a heavy contradiction to the earlier scenes of typical Amish living, with shots of farmsteads and families driving their horse carts. The storytelling here does show itself through the environment and the inclusion of Faron’s hands in the scene adds to the impact of what’s happening in the story. We’ve seen Faron tempted by the English way of living for a while and can see a trend of more and more dangerous substance abuse from drinking to smoking. Seeing his hands packaging “crank” tells the audience that his story has taken a dark dip on his journey in English living. Not quite as effective as seeing facial expressions, since we can’t see Faron’s face as he’s doing this, but we know as the audience he’s participating regardless.

Here we return to human expression as visual storytelling. After Faron gets off the phone leaving his dad a message in Dutch over the car accident he got in, the camera stays on Faron. We see his immediate reaction to the message. Looking down, fidgeting with his clothes, sitting still, all signs that Faron is experiencing emotion. The audience isn’t told exactly what Faron’s thinking, but can infer that he’s thinking about his life, his family, his accident, and ultimately leading the audience back to the theme of Amish vs. English.

Thanks for reading!

Hello class,

Frantic, electric, and cluttered are some of the words this opening scene of Shamelessexpresses in my mind. Continuity carries this scene from shot to shot. A range of frames are used to convey the emotions of the characters and establish the setting for this show. Faces, shoulder-up, moving hands, following-shots, full-body, and jump cuts help to convey the scene’s energetic flow. Visually we can see the cluttered state of the house as the characters move, the camera following the woman for most of the beginning. The camera stays focused on the characters’ movements in this packed setting which adds the feeling of franticness for the audience.

The quick pace of the camera and characters also aids in the sense of energy. We see when the woman calls out for the bill, the camera pans to each kid as they reply with “electric”, which the word play also adds to the feelings previously mentioned. We as the audience follow these shots along with the dialogue to understand how this family works. On top of this, the quick cuts and transitions act like mini jumps in time. There are no pauses really, giving the sense to the audience that this scene is happening all at one time, one thing after another, when the cuts by the camera quicken the time between shots. Had this all been one single shot, we see no cuts to characters, the audience wouldn’t have felt the same.

The quick movements are held in place by the characters themselves and certain actions they do. The woman filling the jug of water, a break from chaos. The woman placing the shirt inside out and backwards on the boy, the boy tossing the phone to the woman, and the woman placing the chair in the washer/dryer to help it work. These scenes outside of the characters still include the frantic movements but take a moment out of dialogue and physical expressions to let the audience catch up with the action.

Thanks,

Caleb

Hello class,

Visual evidence. It’s the key to conveying the documentarians’ themes and ideas to the audience. The essays emphasized the importance of visual evidence. How can someone tell a story without any sound, just visuals? Silent films are prime examples, as the essays point out. Their only option WAS visual evidence. They shot scenes with intention. A documentary highly focuses on the visual with the inclusion of sound to reflect one another. While being in the modern world, how can we tell the story of local nurses during COVID without going inside the hospital? I’d want to tell the story of the physical, emotional, and mental impact the pandemic has over the nurses on the front lines.

“A critical part of the preparation for any documentary project should be to ask yourself what you can show your audience that will help them to understand the subject” (pg. 99).

To tell my story, I’d want to show an interview with a nurse from a local hospital. The audience gets to see behavioral evidence from this interview, the responses to questions about their work, family, and personal life resulting from COVID. However, the essay points out that interviews usually aren’t evidence. How can someone believe what a person is saying if all they see/hear is that person? What does that struggle look like? The essays highlighted the importance of location when conducting an interview.

“If you’re filming an expert on juvenile delinquency who is proposing alternatives to putting adolescents in adult prisons, film her at the prison rather than her office” (pg. 98).

The hospital is off the table. But COVID isn’t solely located at the hospital. The world “pandemic” means affecting the entire nation. Filming this interview in locations that would usually be full of people, perhaps a mall or a school, showing a scene of the interviewee taking off or leaving on their medical mask. These locations point out the impact of COVID on our environment that would allow for the interview to touch on, reflecting points from the dialogue with visual evidence. I would also ask the interviewee if they could supply and photographs of themselves on the job, of their family, or simply include publicly available images of nurses, patients, and other medical staff dealing with COVID.

“You have to plan for filming in situations and at locations likely to provide useful visual evidence, and you must also be prepared to recognize visual evidence when it occurs, even when it doesn’t show up in the way you might have expected” (pg. 99).

A distinction is made about B-roll and visual evidence in the essays. “B-roll mentality” is a worry of the writer that filmmakers fall into. They disregard looking for the scenes that tell the story and instead look for scenes relating to the story.

“Any time a shot in a documentary could be taken out of the film and replaced with something completely different, it’s B-roll. If it has to be there, it’s visual evidence” (pg.107).

A scene where the interviewee is washing their scrubs early in the morning before work tells us just how often this person is working during the pandemic. Another scene of them arriving home late at night after a busy shift. A car ride with the nurse showing their route to work at the start of their shift. These scenes could be replaced with shots inside the hospital if allowed, but the replacement isn’t necessary. These shots tell the story, the struggles of nurses in all aspects of life from the COVID pandemic while at home.

I’ve garnered a new appreciation for the documentarian and the work that goes behind creating a truly authentic story.

Thanks for reading,

Caleb

Hello class,

I chose to look at starwarswars.com and the How Not to be Seen videos.

Starwarswars.com was a project I’d heard about before but had never looked into. This project combines the first two trilogies of Star Wars films and plays them simultaneously, one on top of the other. This was done, as Marcus explains in the about section on the website, through an effect that only displays the brightest pixels in each video layer. He says that’s why Hoth from Episode V takes up a large section of the project as the white pixels of the snow are the brightest.

How Not to be Seen was a trip. I was thoroughly confused at first, but as the video continued, I think I got a grasp at the message behind becoming invisible. Pixel manipulation allows for any object, person, place or thing to be changed or altered on screen. Green screen, resolution, image layering, all are methods used to alter what the audience sees.

Tying these examples to the main question for this blog, how is the realism of traditional cinema challenged by techniques such as this? As the audience, we are keen on determining whether something is real or not. Is this scene CGI or is its traditional footage? Pixels determine what’s visible, and what’s not. As creators, we can choose what we want or don’t want to be seen. We can choose what’s real or what’s not real.

Thanks for reading!

Caleb

Hi everyone,

I chose to look at this clip from Duel.

This was one of the first scenes where the audience truly gauged just how insane the truck driver was. The tension begins with a continuous shot of both the truck and car for about 20 seconds. It’s a long shot for all those seconds until the camera cuts to a close up of David, which gives the viewer the sense he’s going to do something, and indeed he does by pulling off to the gas station.

We see an example of a reverse shot between David and the attendant where the camera goes from a close up of David looking right, to a close up of the attendant looking left, then returning to David. This shows the audience a grand sense of space, being the whole gas station and particularly the conversation between the two characters, while the truck looms ominously in the foreground. A technique not mentioned is the depth of field transitions between David and the truck when David turns to look at it. The camera matches this action in a single shot to show the audience a focus on things going on within the frame.

As David enters the phone booth, the camera cuts multiple times to the truck and back to David as each shot shows the truck moving closer to David. A match-on-action appears when the truck transitions into David’s series of shots as it collides into the phone booth. A cut happens to show David’s realization the truck is heading right for him.

Sound plays a major part in this film, especially for the truck. The horn, the diesel engine and rattling metal add to the suspense brought upon each scene. It’s cleverly used to build suspense, slowing increasing the volume of the engine as the truck approaches the phone booth, and alleviates suspense too when the truck stops moving. Undoubtedly a unique use of cinematography and sound to create a tension-filled experience for the audience.

Thanks for reading!

-Caleb