Author: Victoria

Final Rough Cut – ‘make friends’

1 Minute Movie – ‘the clown’ Rough Cut

Interview (rough)

B-Roll is incomplete.

Post 11/8

My final video idea is a combination of documentary / ‘making of’ film and a fictional concept.

Beginning: At the start, the video would resemble a crafting / ‘making of’ style documentary of a creator crafting a doll. It would follow the steps of creation (not closely, but document the process), until the conception of the doll.

Middle: The video takes a fictional documentary turn, as it follows the creator and the doll living life together. This would most likely be a montage portion showing the depth of friendship between the two.

In the final montage scene, the creator drops the doll in mud, ruining it (?). The scene is held in dramatic fashion for a moment.

End: The video returns to the creator, pacing anxiously around their home in. They begin crafting another doll. This is a repeat of sorts of the first time, sped up and slightly varied to show the change in emotion. This doll is complete, different than the first. The creator hands Doll 2 a bucket and towel, and Doll 2 cleans Doll 1 for them, and all is well.

Montage – ‘What’s that Post Malone song called again?’

Circles

Post 5: Compositing, Effects & AI Cinema

In ‘Posthuman Cinema’ by Will Luers, Mark Amerika, and Chad Mossholder, the viewer is shown worlds both based in reality and completely generated by computers. The result is jarring and evolving, with a variety of styles produced. The clips vary from resembling old, degraded film to complete CGI animation, moving between a multitude of styles. The environment depicted in ‘Infinity Forest’ is mostly natural with humans as the focus. These environments, in combination with the AI generated visuals, create a fantastical and alien feeling.

While some of the generated animations have ‘incorrect’ and sometimes scary effects, these can add to the narrative or mood of the experience as ‘posthuman’. For example, in ‘Infinity Forest’, there is an ECU of a human(oid) eye. While it may just be an ‘incorrect’ depiction of an older human, the errors evoke feelings of an ape-like creature and can hint to themes of evolution.

Additionally, the use of AI generation and natural imagery, such as mushrooms, further pushes the feeling of evolution and somewhat alien aesthetics. Mushrooms, with their decomposing ability, can be unnerving to many humans. This is aided with the AI generated images, which can also be unnerving in its ‘uncanny valley’ effect.

These techniques, in my opinion, mostly challenge the idea of realism in traditional cinema. Due to the constantly evolving movement of the generated people, trees, and general images, it is hard to complete grasp onto realism in the videos. However, as I suggested earlier, rather than allowing this distance from reality to detract from the work, the creators used it to push the narrative further and create a clear exploration of cinema without clear traditional realism.

Post 4: Window / Okno

Sources (freesound.org):

Door opening with handle. By 1234Thekrebwgus

clean footsteps in shoes on soft surface by busabx

Radio receiver on/off by LukaCafuka

Radio noise and static by LukaCafuka

Gasping by 9voltfan

Running Carpet by LewisEmmott5

cutting keys.wav by modcam

Door Slam – No Reverb.wav by adriann

In Class Montage

Jeremy Sauter and Victoria Clark

Continuity – ‘can’t find lil buddy’

Post 3: Continuity – Shameless

One of the most commendable traits of ‘Shameless’ is its ability to create unbelievable situations that unfold in somehow believable ways. While, realistically, the audience knows that these events cannot unfold so quickly in real life, the quick and clean editing allows for a strong, yet chaotic, continuity.

Throughout the scene, we follow a variety of objects as characters pass through the house, focusing on key objects that the characters interact with in turn (i.e. the bathroom door, the calendar, the cereal box). While items of interest are passed from character to character, the audience is introduced to each of them and part of their role in the family. The quick movement of certain objects (throwing the phone across the room) allows for the camera to change to be fast but maintain a cohesive scene.

Another interesting editing trick used is keeping more than one character in frame for most of the screen time. This allows the viewer to absorb more visual chaos as they see multiple characters completing actions at the same time, with some of these actions passing from one character to another as well. This is controlled by one of the actions being more ‘dominant’ than the other, such as one character filling out a form while others do the simpler action of pouring cereal.

In-Class Continuity Assignment

by Victoria Clark and Jeremy Sauter

Framing – ‘dog destruction’

Post 2: Continuity – Duel Ending Scene

In Steven Spielberg’s early film ‘Duel’, he masterly utilizes many continuity tricks in quick order to create drama and emotion. During the ending scene, the success of these edits builds the scene to a dramatic climax and conclusion.

The final 4 minutes begin with a ‘Motivated POV’ shot of the protagonist, David, as he sits in his car, staring out. He watches the empty road, waiting for the Peterbilt truck that’s been chasing him to emerge. This second shot, waiting for the truck, is an ‘Empty Frame’. This builds the viewers tension as they wait for the inevitable.

The ‘Motivated POV’ repeats as the truck starts barreling down the road towards him. This is also a ‘Shot Reverse Shot’, as David sees and then reacts to the truck.

There is then a ‘Match on Action’ edit of the truck, zooming in dramatically with a shaking camera. The viewer sees David again from the front, before switching to a shot of him from behind, following the ‘180-degree rule’. These dramatic changes of framing maintain the intense and quick pace of the plot.

Spielberg then uses ‘Parallel action / Crosscut’ edits of David’s car and the truck speeding towards one another from the front, which could be considered a ‘Graphic Match’(?) of the trucks front and the cars.

The shots shown of David’s car as it collides with the truck follow the ’30-degree rule’, changing from the front right to the far back left of the car as it is struck. This allows the viewer to see the collision more clearly, while maintaining a sense of positioning relative to the car.

By using these editing skills throughout the ending, Spielberg builds and maintains the intense and frightening pace and tone that has been built throughout the film. This is necessary for creating a climax and conclusion that can satisfy a viewer who has been made tense alongside David for the entirety of their viewing experience.

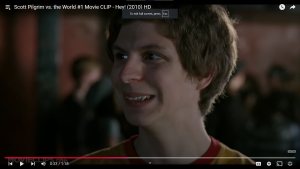

Post 1: Framing – Scott Pilgrim vs. the World

In ‘Scott Pilgrim vs. the World’, unique camera and framing tricks are used to highlight drama in the story, allowing for emotions the characters are feeling to be expressed without words in a very quick and effective manner. In this scene, many of the shots are medium close-up (MCU) of a certain character, but often include other characters in dynamic ways.

https://youtu.be/R-aJ-2y5ICo?si=yxFdUZORi_018pxq

In this scene, we see Scott at a his band’s show, which he has invited Ramona Flowers (his crush) to. As she arrives, she meets his band and friends, including his current girlfriend, Knives. As Scott deals with his mistake, the viewer sees the tense game of emotions being tossed from person to person.

In the first shot, we see Ramona at close-up (CU) between Scott and Knives, who have just kissed and are at extreme close-up (ECU). This begins the loop of tension moving throughout the characters.

The screen then shifts to CU of Scott, who looks from left to right in one shot. Even though the viewer can’t see what he’s looking at, the preceding and following shots, as well as the emotion, help tell the audience who he looks to and from (Ramona to Knives).

As Scott looks at Knives, the shot changes to a CU of her. Included is a MCU of Wallace (Scott’s roommate), which helps establish where everyone is within the shot.

The shot then zooms out, becoming a MCU of Knives and a CU of Ramona, showing Knives’ tension towards her.

It then switches to a CU of Scott’s sister, showing an CU/ECU of Knives in front of her, looking the same direction.

When the shot zooms out, we see that they are both looking at Scott, who is now CU. This exemplifies their anger at him.

Then the shot changes to a CU of Wallace-

–who is looking towards Scott’s sister’s boyfriend, setting up tension on the side as well, as Wallace is attracted to him. The boyfriend looks away uncomfortably.

It then switches to the final CU of Scott, the instigator of the entire problem.

The audience then sees a medium shot (M) of everyone looking at Scott, showing the bulk of people who are upset with him after focusing on each of them one by one. This passes the tension from character to character, shot to shot, quite smoothly.

Finally, the camera then shows the final CU of Scott again, before he runs away from his problems, as is common for the character. The camera stays in place as he escapes, showing the ECU back angles of Ramona and Knives as Scott goes from CU to long shot (LS).

Overall, this playful and dynamic use of framing and zooming out allows the viewer to digest a large amount of information rather quickly and easily. It keeps the viewer more engaged than if each character explained who they were upset with and why. Additionally, the repetitive nature of the shots zooming out adds to the tension of the narrative, as the viewer isn’t sure who is going to be seen next or how deep each character’s emotions actually run.