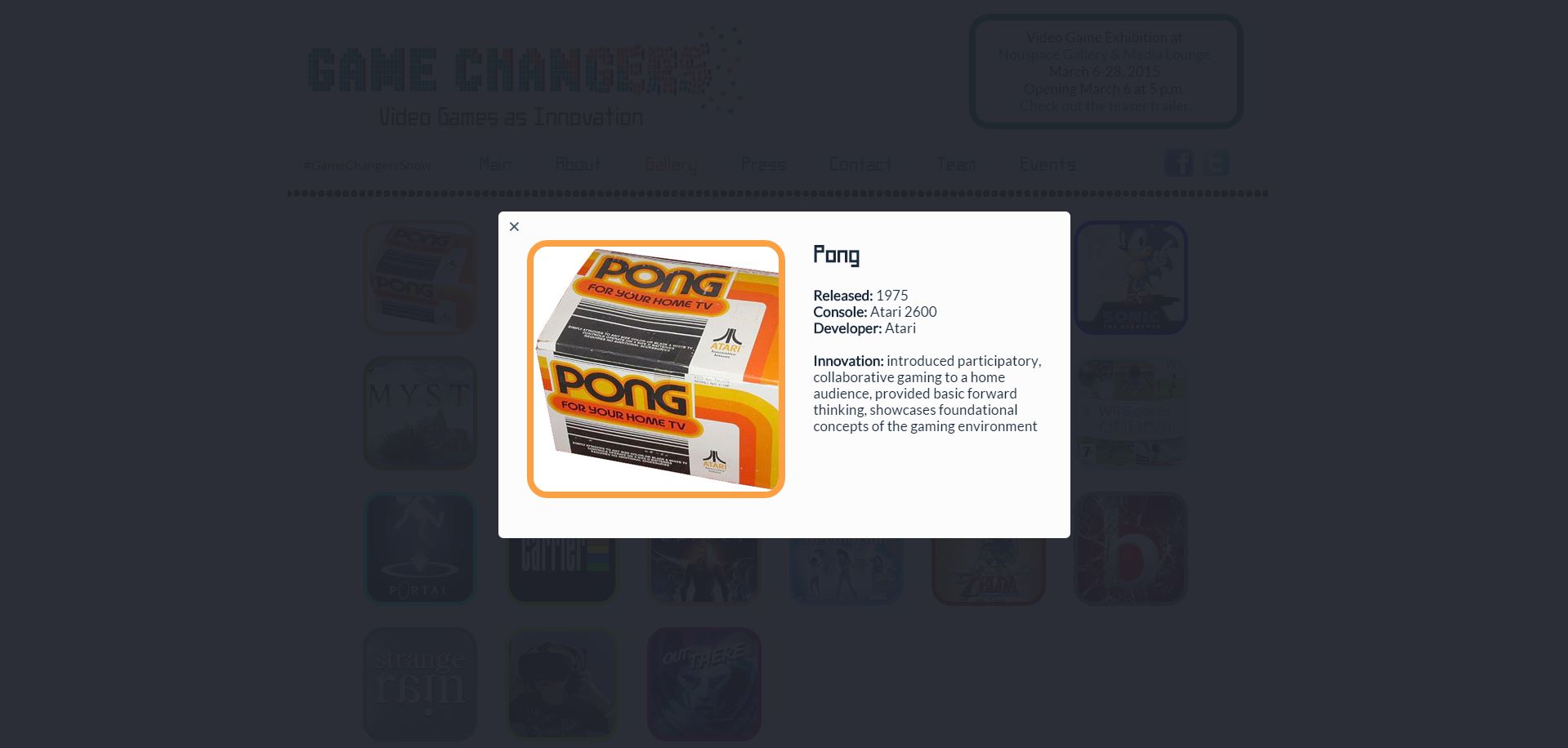

This semester in university provided me with many valuable experiences, but none as deeply enriching as my DTC 338: Exhibit and Archives course. The class was more than just a primer for curatorial and archival methods — it was a laboratory for practice-based research and collaboration. This experience shaped me immensely, especially when I volunteered to coordinate and curate Game Changers: Reinventing Storytelling Through Video Games. This exhibit ultimately became an opportunity for practicing the ideas we examined in class within the two books: Ten Fundamental Questions of Curating and Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Curating* But Were Afraid to Ask. This was a fundamental learning experience that constructed my thoughts and perceptions concerning what it means to be a curator and what is involved with curating an exhibit.

Of the chief principles that I was exposed to, the definition, role, and purpose of a curator was articulated among our texts:

“a vast, all-encompassing category embracing many workers in the field of visual arts, including education and the many disciplines that are (finally) incorporated into the panoply of an exhibition-making arsenal” (Morgan, 21).

Ulrich-Hans Obrist furthers this notion by stating that:

“the role of the curator is to create free space, not occupy existing space … connecting different people and practices, and causing the conditions for triggering sparks between them” (166-167).

Without a doubt, these statements, and others, encouraged me and situated my skills into the role of “curator.”

The first job in this position was to determine the collection of video games to exhibit — an array of diverse titles that touch upon various narrative styles, game mechanics, and genres. With the help of my colleagues, a selection of video games that best represented reinventions in storytelling was decided upon. This process was terribly difficult, and made me aware of the struggles involving choosing one work over another and the importance of creating a strong curatorial vision.

Part of what Obrist believes is intrinsic and inseparable from this vision, is the production of conversation among temporary communities. I had never thought about exhibit interactions in this way before (which is probably due to my quiet nature). In past exhibitions, I only ever talked to those within my immediate viewing group. However, at Game Changers, I saw the benefit of inspiring conversation among different individuals — especially since each video game playthrough is unique in it of itself. Throughout these interactions we created a space to scrutinize, postulate, and collaborate — a “place for us to take the risk of reading an artwork against the grain of its already accepted historical meanings” (Filipovic, 80).

In conjunction with the new ideas I learned through reading and practice, I acquired leadership experience. Be it from my interaction with the class or from my correspondence with independent game developers, I learned about what is known as “curatorial responsibility” (Eleey, 113). In Game Changers’ case, this meant putting the artist first — allowing developers the independence to speak about and display their work as most pleases them. This responsibility also translated into treating the various teams within the class with respect and making sure that everyone was accounted for.

As displayed above, this semester in our class was a crucial learning experience for me, not just for taking on the role of a curator, but also for future positions in which leadership and responsibility are key. Game Changers 2016 allowed me to demonstrate my skills and talents, as well as my passion for video games. I will look back on this year with warmth and appreciation knowing that, for that one month, we managed to introduce hundreds of people to the power of video game storytelling, creating what Obrist calls an “ephemeral constellation.”