Have you ever stopped to think about what gives words their weight? They’re the tools we use to convey thoughts, feelings, and ideas. But they’re not just fleeting sounds or scribbles on a page. Let’s take a closer look at why words are more substantial than we might realize.

At first glance, it’s easy to see words as mere blips in conversation, here one moment and gone the next. But if we dig a little deeper, we’ll find that words have a tangible quality to them. When we speak or write, we’re not just making noise or marks on paper. We’re shaping something real, whether it’s the vibrations in the air or the ink on a page that represents our thoughts and meanings.

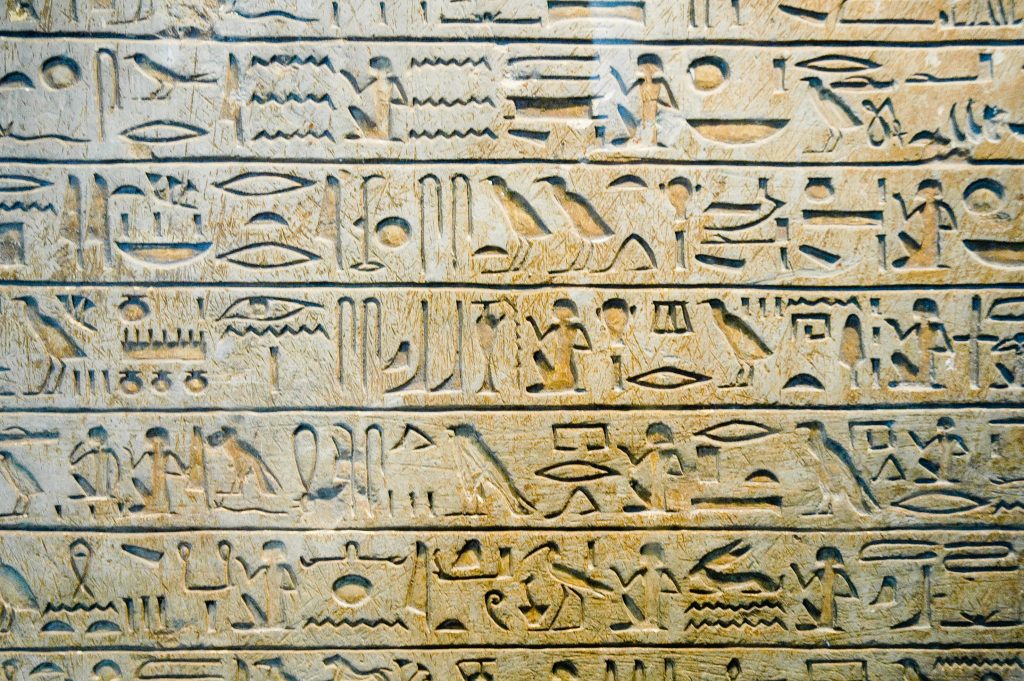

Think about it. When someone says “tree,” it’s not just a sound that disappears into the air. It conjures up an image in your mind, one that can stick with you long after the word has been spoken. And it’s not just spoken words that have this lasting impact. Ancient texts carved into stone or written on scrolls have survived for centuries, reminding us of the enduring power of language.

Words also have the power to shape the world around us. From political speeches to religious texts to beloved novels, words have the ability to move us, inspire us, and change the course of history. They’re not just fleeting events but powerful forces that can spark revolutions and unite people in a common cause.

But perhaps the most remarkable thing about words is their ability to transform. A single word can carry a world of meaning, evoking a range of emotions from joy to sadness to anger. Just think about how “I love you” can strengthen a relationship or how hurtful words can leave lasting scars.

In essence, words are more than just sounds or symbols. They’re tangible entities that have a real impact on the world around us. So the next time you speak or write, take a moment to appreciate the weight of your words. Remember that behind every fleeting moment lies something solid and enduring. Something that has the power to shape our lives in ways we may not even realize.