Here is a sort list I have of static image generation. I have run all of these through Adobe’s AI service in Photoshop just to get an idea for style and what the shot might look like. Some of these have varied styles, but I am going for more of the yellow photograph style, and moving away from the illustrated style. Here are my shot descriptions and some of the photos I generated. As I begin the process of working with the video service, I will alter the prompts to add movement in the shots.

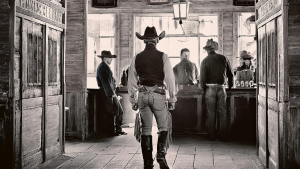

Shot 1

give me a photo of a cowboy entering a saloon with swinging doors. This cowboy will have his face hidden under a cowboy hat, and the saloon will have many guests all turned towards the cowboy. This photo will be in the old west style, very yellow and in the style of an old photograph

Shot 2

give me a photo of people from 1882 playing cards at a table in a saloon from 1882. The players should be playing poker with a classic deck of playing cards, and on the table there should be money, pokerchips, and alcoholic drinks. This photo will be in the old west style, very yellow and in the style of an old photograph

Shot 3

Give me a photo of a bartender from 1882 making drinks in a bar with lots of guests. The guests are on the other side of the bar, and the bartender is giving them drinks. Focus on the bar tender. This photo will be in the old west style, very yellow and in the style of an old photograph

Shot 4

Give me a photo of people sitting at a table in a bar from 1882 looking up from their drinks. Have them looking at the camera. This photo will be in the old west style, very yellow and in the style of an old photograph

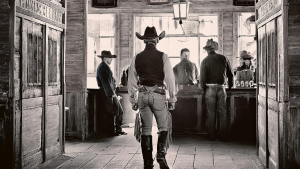

Shot 5

Give me a photo of a cowboy entering a bar in 1882 with swinging doors. This cowboy will have his face hidden under a cowboy hat, and the bar will have all the guests all turned towards the cowboy. Have the camera focus on his hand as it reaches for his pocket. will be reaching for something in his pocket This photo will be in the old west style, very yellow and in the style of an old photograph

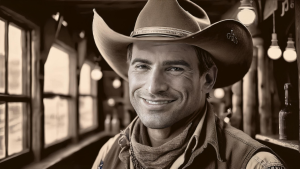

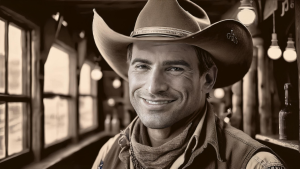

Shot 6

Give me a close up on a cowboy’s face as he smiles. This photo will be in the old west style, very yellow and in the style of an old photograph

Shot 7

Give me a cow standing in a bar from 1882. This cow should have a gun and be wearing a cowboy hat. This photo will be in the old west style, very yellow and in the style of an old photograph. Have him be half human with human limbs. Show full body

Shot 8

Give me a cow standing in a bar from 1882. This cow should have a gun and be wearing a cowboy hat. This photo will be in the old west style, very yellow and in the style of an old photograph

Shot 9

Give me a photo of a bartender from 1882 making drinks in a bar. The guests are on the other side of the bar, and the bartender is giving them drinks. Focus on the bartender. The bartender is pouring a glass of milk. This photo will be in the old west style, very yellow and in the style of an old photograph