Dyslexia

What is Dyslexia?

Dyslexia is a language-based learning difference that usually impacts reading the most, though it can affect oral pronunciation of words as well. People with dyslexia typically have lower reading levels, despite being at a normal intelligence level. Dyslexia was initially coined as “word blindness,” and later changed to be called dyslexia, which is of Greek origin. It means “dys”, difficulty with, and “lex” (from legein, to speak), having to do with words.

According to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) which was amended in 2004 and 2015, the definition of dyslexia is, “a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or in using language, spoken or written, that may manifest itself in the imperfect ability to listen, think, speak, read, write, spell, or to do mathematical calculations, including conditions such as perceptual disabilities, brain injury, minimal brain dysfunction, dyslexia, and developmental aphasia.”

Here’s a great video by Kelli Sandman-Hurley, a well established dyslexia expert, explaining what exactly dyslexia is:

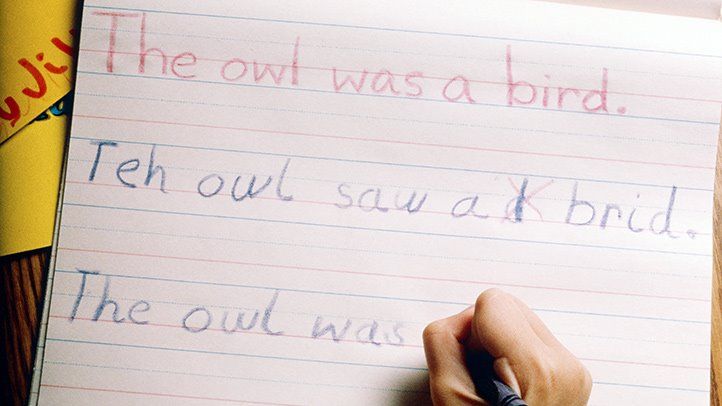

What Does Dyslexia Look Like?

Here is some simulated text to showcase what dyslexia may look like to someone who has it:

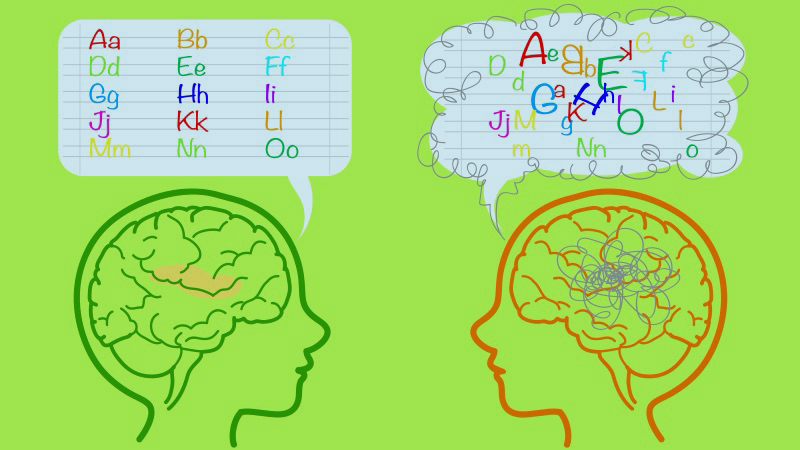

What Causes Dyslexia?

The cause of dyslexia is linked to genetics, which is why the condition often runs within families. The conditions in which dyslexia stems from are the different processes in language and writing within the brain. According to Webmd, “Imaging scans in people with dyslexia show that areas of the brain that should be active when a person reads don’t work properly.”

How is Dyslexia Diagnosed?

Students at a young age can help determine their reading level. Those who are affected by dyslexia find that their reading levels aren’t progressing along with their peers. When dyslexia goes undiagnosed it creates difficulty in executive function.

When diagnosing dyslexia, there are multiple methods that come into play:

- Developmental history

- Medical history

- Questionnaires

- Physiological and Neurological tests

- Psychological Evaluation

- Academic testing

What Are The Statistics?

- 20% of school-aged children in the US are dyslexic

- 70-80% of students with specific learning disabilities receiving special education services have deficits in reading.

- Dyslexia affects males and females nearly equally as well as, people from different ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds nearly equally

- It is estimated that 1 in 10 people have dyslexia

- Over 40 million American Adults are dyslexic - and only 2 million know it

What are Some Ways to Combat Dyslexia?

The single most important way to combat dyslexia is for students to receive the right type of reading instruction. Decades of research show that Orton-Gillingham based methodologies, also known as structured literacy, are the most effective way to teach students who have a diagnosis of dyslexia, or risk factors for dyslexia. Samuel Orton found through his research that many students who were at the time thought to be “slow learners” actually could be taught to read using these different strategies. Anna Gillingham and Bessie Stillman developed and outlined the teaching strategies that are still being used by dyslexia intervention practitioners today. The obstacle to receiving this flavor of reading instruction is that there are not enough trained professionals to deliver it. One very important step in combating dyslexia is to increase reading expertise among teachers at the teacher preparation level. Until states and districts (and corresponding university teacher prep programs) require K-3 teacher candidates to take coursework in the science of reading** like the state of Colorado has done, we will continue to see a shortage of trained professionals, with young readers being the largest casualties. If about 80% of students are typically developing readers and up to 20% of students have some degree of dyslexia, then the lack of trained teachers in dyslexia remediation becomes an equity issue. Do we consider leaving 20% of young readers behind an acceptable loss? Several states have laws to screen for K-2 students who may be at risk for dyslexia, but once found to be at risk, if there are not teachers trained in how to effectively provide intervention, the students still lag in reading progress, as evidenced by the 2019 pre-COVID NAEP scores. Only 35% of 4th grade students were at or above proficient in reading in the state of Washington.

The key idea behind Orton-Gillingham based methods is that teaching should be direct, systematic, cumulative and multisensory. Direct instruction means that students are directly taught each concept to mastery in both reading and spelling. Teachers do not assume that students will realize that the suffix -ed has three different sounds– /d/, /t/ and /id/. They explicitly teach this concept, along with when it makes each of the three sounds. Systematic means that a teacher should be moving through a scope and sequence from least difficult concepts to more difficult concepts. A more difficult concept should not be introduced until the student reaches at least 80% accuracy in both reading and spelling on every concept taught prior. For example, “Silent e” should not be introduced if the student is only at 60% accuracy with beginning blends. If they are still struggling with blends, it’s not prudent to add a new, even more difficult layer. Many advocate not introducing something more difficult/complex until the student is at 85-90% accuracy in both reading and spelling. Cumulative means that while new concepts may be introduced during one lesson, there will still be a portion of the lesson devoted to reviewing concepts previously taught so that they don’t fade out of the students’ memory. Finally, multisensory instruction helps the concepts be mastered more quickly and in a stronger way because multisensory teaching causes more parts of the brain to be activated. The goal is to have hand, eye, ear and mouth all working together during each part of the lesson, several senses simultaneously (SSS), on the theory that the brain that fires together, wires together. As evidenced by the latest imaging research using fMRI technology, Orton-Gillingham based interventions literally increase the neuronal connections related to reading in the brain over time, and help students learn to read.

**If you scroll down to the heading called “In-service,” it talks about how all K-3 teachers must receive a certain number of hours in evidence-based reading instruction.

ImprovingLiteracy.org/State-Of-Dyslexia/Colorado

For adults, it’s never too late to get the help necessary to carry out life goals. There are resources to get institutional help along with services required by employers per the Americans with Disabilities Act. Dyslexia is a challenge that doesn’t affect intelligence and because dyslexia is a common learning differences there are resources out there.

Here is a video created by Get Ready for University that discusses Hannah’s, a university student, ways with dealing with dyslexia while being a student:

Here is a video by Ana Mascara on study tips for dyslexic students: