"Digital Dynamics Across Cultures re-imagines the work of anthropology in the age of digital reproduction, and, by extension, explores the cross-cultural implications of several seeming truisms of the electronic era. While the libertarian impulses and voices fueling the gold rush mentality of Silicon Valley's dot.com period often insisted that 'information wants to be free,' Kim Christen here reveals the peculiarly Western bias of such claims. Drawing on materials collected in more than a decade of field work, Christen and her collaborators have created a complex, multimedia artifact that moves far beyond Discovery Channel-type explorations of cultural difference. Instead, the project models the unique systems of belief and of shared ownership that underpin Warumungu knowledge production and reproduction, including a system of 'protocols' that limit access to information or to images in accordance with Aboriginal systems of accountability.

The site is experiential, but it does not presume cultural experience to be something we should take for granted as a birth right of the digital age. Digital Dynamics Across Cultures does not invite the (Western) viewer to 'become Aboriginal' or to assume another's identity, that avatar-based standard of so many products of digital culture. Rather, the experiences it constructs are partial, embedded, and provisional, barring access to specific images or performances, in a manner consistent with the logics or protocols of the Warumungu people. As such, the site stages a series of complex negotiations that trouble easy binary assumptions about the nature of intellectual property, the boundaries between the public and private, and the relationship of self to both place and history.

Digital Dynamics Across Cultures denies the tourist's gaze, refusing to fix the Warumungu as objects for our consumption, either embalmed in a distant past or locked in an electronic present. The algorithmically-driven database structure of the project means that only a small slice of its vast contents is available during any one visit. The materials available for exploration shift and mutate with each click of the refresh button, highlighting the ephemeral nature of digital forms and of any sense that we might systematically be able to know 'the Other.' The project also demands an ongoing process of collaboration and dialogue between Christen and the Warumungu, as the protocols it models require that the database be consistently updated to reflect changes in the community. Such a process underscores that the mutability of digital forms reaches far beyond the database to the lived worlds we all inhabit." – Vectors Journal Editorial Staff, Vectors, Volume 2, Issue 1, Fall 2006

Author's Statement

"This project grows out of my collaborations with Warumungu people in Tennant Creek, N.T. Australia over the last ten years. During this time, I worked with rotating groups of Warumungu men and women on a range of projects — all of which involved taking photographs and digital video recordings. Although the projects culminated in various 'products,' in every case, we were guided by a set of cultural protocols concerning the circulation, creation and reproduction of Warumungu knowledge and traditions. This meant, for instance, that some ritual songs we recorded could only be heard by women, or that some photographs could only be viewed by particular family groups, or that particular video footage of ancestral sites could not be viewed by the uninitiated.

At the most basic level this system operated within the logic of an 'open'/'closed' binary. Some information is open, anyone has access. Other material is closed, only those with the proper knowledge have access. Yet the binary does not hold. Instead, there is a continuum between open and closed. Within this continuum various factors determine levels of access, gradations of control and multiple levels of engagement. These factors include (but are not limited to): gender, age, kin relations, country affiliations, and ritual knowledge. This is a dynamic system, then, that allows for the continual remaking and repackaging of Warumungu knowledge and tradition within various networks. And because Warumungu social networks include land ('country'), other-than-human relatives ('ancestors'), local kin groups ('mobs') as well as outsiders, the maintenance and creation of 'proper'—but not static—traditional knowledge and cultural products involves constant negotiation. (For my article that develops this further see: Gone Digital)

Warumungu cultural protocols concerning authorship, ownership, viewing practices and knowledge creation are an intellectual property rights (IPR) system — a set of standards and limits for the use, redistribution, and reproduction of knowledge in its intangible (and tangible) forms. But the links between these Warumungu digital dynamics and the national and international legal systems in which they circulate are not stable. Legal regimes that demand a rigid public/private split and an author-centered notion of production deny Warumungu notions of property, access and circulation that are based neither on individual nor communal ownership. Instead, Warumungu groups base their distributional imaginary within dynamic relationships between small groups of people, related countries and ancestral relations.

This Vectors' site is designed to make Warumungu cultural protocols for the distribution, reproduction and creation of knowledge the primary logic. This is not a learning site — in the sense that users will come away knowing about 'the Warumungu' in any complete sense. In the design concept we wanted to stay away from what I clumsily labeled a 'video-game' feel. That is, we did not want to give users the 'experience' of being (via an avatar-like persona) an Aboriginal person for a day. Nor did we want people to feel as if they could learn about Warumungu culture 'whole cloth' through this site. This was not because of some lurking Luddite sensibilities or a knee-jerk Humanities reaction to 'dumbing-down' the complexity of cross-cultural exchange. Instead, the site is deigned to alter the way in which 'learning' about other cultures is perceived and presented.

By presenting 'content' through a set of Warumungu cultural protocols that both limit and enhance (depending on who you are) the exchange, distribution and creation of knowledge, the site's internal logic challenges conventional Western notions of the 'freedom' of information and knowledge 'sharing' as well as legal demands for single-authored, 'innovative,' original works as the benchmark for intellectual property definitions. As users navigate through the site, they will encounter the protocols that limit, define and account for a dynamic and multiply-produced understanding of knowledge distribution and reproduction." -- Kim Christen, Vectors, Volume 2, Issue 1, Fall 2006

Designer's Statement

"When I first spoke to Professor Kim Christen and Chris Cooney about the design for Digital Dynamics Across Cultures, I was immediately struck by the challenge (and the apparent paradox) of building an interactive piece that centered around information that could not be freely shared. Kim had amassed this vast library of images, videos, and recordings of Warumungu society, precisely the kind of content that one would normally want to display, but that, in the context of this project and Warumungu culture, could not be openly viewed. If we were going to make our point, it couldn't be through what we showed. It would have to be through what we didn't show or what we chose to conceal.

THE BACKEND

The first step was to store and organize all of Kim's content in a database. A database would give us flexible control. Craig Dietrich and I set up a system whereby Kim and Chris can easily update, modify, add or remove content, and, most importantly given the cultural protocols they are dealing with, control whether or not a particular image, video, or other element appears online.

Because of the sheer quantity of content, Craig and I then set about creating an algorithm that sifts through the database and pulls a representational assortment of content which I then use to populate the Digital Dynamics Across Cultures site (the frontend) -- enough content for Kim to make her point but not too much so as to overwhelm the user. This algorithm also ensures that each visit to the site is unique: each visit uses a different assortment of content to make the same argument.

THE FRONTEND

I should begin by saying that the site itself, what you see when you access the project, is completely dynamic in all aspects: from the number of places that appear on the map, to the images and text displayed on the page, they are all determined by and will vary based on what Kim and Chris upload to the database.

So how should the user experience all of this content? Since place is a defining element in Warumungu society, I chose an abstract painting of a map of the Warumungu community as my initial source of inspiration for the primary navigation system. Kim, Chris and I all agreed, however, that we shouldn't get overly literal in our implementation of a map, so the interface was never intended to function as a 'real' map. The relative position of each place remains constant to give the interface a sort of geographical grounding, but the map the interface represents is not to scale and the geographical relationship between each place is only roughly approximated. Moreover, much like the content that populates the site, the absolute position of each place varies with each visit. In effect, the places aren't really physical places at all -- more like digital repositories of cultural information (some of which is inaccessible) hovering around a digital focal point . . . much like the site itself, floating somewhere out there in cyberspace.

The secondary interface, that kind of single-celled organism that splits and divides when interacted with, was also inspired by Warumungu paintings, but, for me, also captures the spirit of exploration that the site demands from the user. Dig around a little, and see what pops up. Learn about the protocols through direct experience, as you travel through this virtual landscape and interact with its inhabitants, and not only by reading about them in a book.

The protocol elements that appear throughout the site (the pop-up windows, the tape mask) and that are ultimately the central focus of the project are meant to be jarring and slightly disruptive. We want the user to come across a few road blocks as he or she explores the site, and to have that experience be educational, a kind of negative reinforcement, if you will." — Alessandro Ceglia, Vectors, Volume 2, Issue 1, Fall 2006

Producer's Statement

"The concept for Digital Dynamics Across Cultures is a virtual space for non-Aboriginal people to engage with Aboriginal cultural protocols. The vision is a dynamic and evolutionary site grounded in the necessary viewing restrictions required by Aboriginal systems of accountability. The interface to the content is experiential, utilizing the non-linear and generative aspects of database-driven multimedia.

The majority of the video and photographic content on the site is from Dr. Kimberly Christen's 10-year collaboration with members of the Warumungu Aboriginal community in Tennant Creek, Australia. The goal of Kim's photographic and video gathering was to document and preserve stories and historical information for later translation and transcription, not to visualize a complex protocol system for public viewing. This posed the challenge of how to repurpose this existing content while preserving the integrity of the information.

The primary content and production challenges of the project were:

- Distill hundreds of hours of video footage and nearly 1000 photographs into focused 'content groups' which address specific cultural protocols

- Establish a comprehensive and extensible information structure that allows for content management and presentation consistent with Aboriginal cultural protocols

- Create a compelling and usable interface that is familiar to both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal audiences

TOO MUCH CONTENT

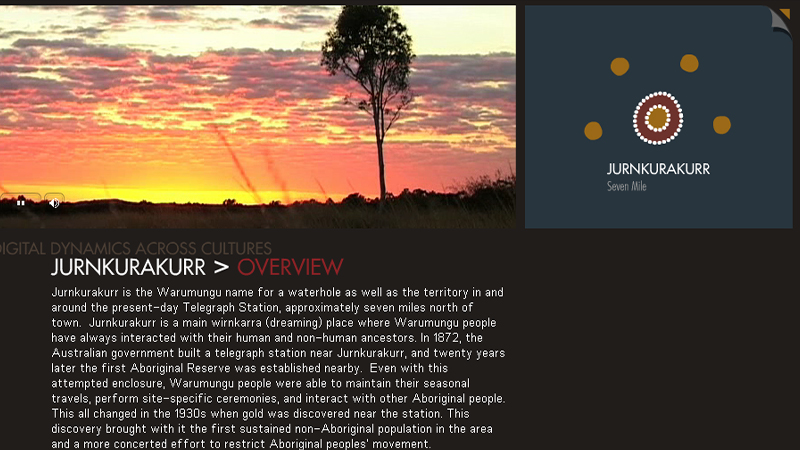

Our first level of selection and grouping of content was by location, as 'country' or place is central to Warumungu culture. Presenting the content in this way highlights the differences and similarities of each of the sites.

Our initial concept for the second level of content grouping was using historical contexts familiar to both the Aboriginal community and researchers working in Tennant Creek. The initial categories (mining, settlers, missions, Aboriginal, other Aboriginal) made it easy to select appropriate content. These were mapped to the interface as 'tracks' connecting each place and shown as a group of 'nodes'. However, as we started to work with these content groups within the interface, it became clear that this approach was muddying the intended purpose of the site: to make Aboriginal cultural protocols evident.

The primary purpose of the site is to demonstrate how Aboriginal cultural protocols function in relation to knowledge production, reproduction and reuse, not necessarily to educate people about other aspects of Aboriginal culture or the history of the region. We decided that each group of content should call attention to a specific cultural protocol and direct learning toward that goal. This resulted in much less explanatory text and more concise content groups, relying on visual and audio to set tone for the specific protocol, rather than explain another level of information.

INFORMATION STRUCTURE

I will leave the detailed discussion of the workings of the backend to our collaborator Alessandro Ceglia. However, I would like to comment on the intention of its design and an unfortunate test it faced during production.

Early in the design phase we decided the site would not attempt to fully emulate the 'rules' of Aboriginal cultural protocols through role playing where a user could take on various 'roles,' then experience each based on complex algorithms modeling protocols. However, elements of this modeling were required for the backend system to allow Aboriginal content owners to manage display of information. Aboriginal protocols dealing with the death of a community member require that when a person passes away their image is not displayed publicly for a specified period of time. It was critical that the system allowed for this functionality.

Shortly before public launch of the site, an elder member of the community passed away. We consulted with the family of the deceased, who requested that the images of that person be taken down from the site for a period of three months. The content management system allowed that change to occur instantly site-wide, while maintaining the original content for when the family chooses to allow it to be shown again publicly.

INTERFACE

'Place' was chosen as the key paradigm for the interface design and gave a common ground to orient both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal users.

Historical tracks, which over the course of the design process had been relegated to a sorting criteria on the backend system, resurfaced on the interface as a way to show progress through the site. These tracks are shown alongside traditional Aboriginal tracks, placing emphases on the new tracks created in this virtual space.

We now had a solidly maintainable information system and grounded interface of place and tracks. What was missing was the most crucial aspect of the interface, the need to disrupt expectations for both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal audiences. The intended effect is to momentarily jar the user, calling attention to the fact this is neither a cultural learning site nor a space for open sharing of content. Alessandro's use of unconventional navigation elements, analog masking techniques, and design of the protocol interfaces accomplishes this goal.

The 'rough', un-staged nature of much of the content further acts to disrupt expectations. The linear visual narrative is disrupted not just by navigation and protocol dialogs, but also the contrasting images and style. Footage of traditionally painted, bare-breasted women doing a ceremonial dance is juxtaposed with an elderly woman wearing a 'Deuce Bigalow' shirt, then an image partially obscured by a piece of masking tape, followed by audio explaining a protocol in unfamiliar Aboriginal English.

The interface allows for these cinema-like edit points to occur within an entirely dynamic system ' ' one that is grounded in the protocols it aims to reveal to users in new and hopefully enlightening ways." -- Chris Cooney, Vectors, Volume 2, Issue 1, Fall 2006

Project Credits

"Artists:

Judy Nakkamarra Nixon

Peggy Napangardi Jones

Lindy Brodie

Rose Namikili Graham

Thanks to these artists for their contributions to the graphics on the main page and the protocol animations throughout the site as well as in some of the content [groups]. . . .

Narration:

Junior Juppurla Frank

Rose Namikili Graham

Dianne Nampin Stokes

Edith Nakkamarra Graham

Thanks to the Warumungu community members who lent their voices to narrate the protocol animations throughout this site.

Community Consultation:

Michael Jampin Jones

K. Nappanangka Fitz

E. Nappanangka Nelson

Dianne Nampin Stokes

Patricia Narrurlu Frank

Edith Nakkamarra Graham

Rose Namikili Graham

Junior Juppurla Frank

We appreciate the guidance of these community members as we undertook the task of translating Warumungu cultural protocols into the languages of new media.

Design Concept:

Michael Jampin Jones

Edith Nakkamarra Graham

Alessandro Ceglia

Christopher Cooney

Kimberly Christen

We could not have undertaken such a project without the help and generous support from Jampin and Nakkamarra.

Photos and Video:

All photos and video taken by:

Kim Christen

Chris Cooney

Paul Cockram

Gary Warner

*except: Banka Station footage: copyright Australian Broadcasting Commission

Permissions:

All images of Warumungu people and places have been generously shared with the permission of the neccessary individuals. No content may be reproduced from this site without permission. Those seeking permission should first contact Kim Christen at kachristen@wsu.edu.

— Kim Christen, May 19th, 2008

Kim Christen

Author

Kim Christen is an Assistant Professor of Comparative Ethnic Studies at Washington State University. Her research focuses on contemporary indigenous alliance-making. Her most recent project examines the intersection of local and international intellectual property rights systems, the information commons and the uses of new technologies by indigenous peoples to both preserve and produce cultural products and knowledge. Her work is based on ten years of fieldwork and collaboration with Warumungu people in Central Australia.

Chris Cooney

Producer

Chris Cooney is a digital media producer specializing in video and new media. Chris has over 13 years experience in communications media including: strategy, design, production and project management. Chris has worked for clients ranging from Fortune 100 corporations, federal government organizations and Australian Aboriginal communities.

Alessandro Ceglia

Designer Programmer

Alessandro was born in Milan, Italy and was educated in the U.S. He received his B.A. from Dartmouth College in Art History and Asian Studies, and then spent five years abroad in various parts of Asia and Europe. He returned to the U.S. in 2001 to work as an interactive designer and developer. He is now based in Los Angeles, and continues to work on interactive projects while pursuing an M.F.A. in animation and digital art at USC's School of Cinematic Arts.

Craig Dietrich

PHP/XML

Craig teams with scholars and designers on Vectors projects solving creative and information challenges, and creates tools for online art & humanities production. His recent collaborations include the Mukurtu Archive and Plateau People's Web Portal content manager based on Aboriginal cultural protocols, ThoughtMesh, a semantic online publishing system, the Dynamic Backend Generator, a MySQL-based relational data writing canvas, and an upcoming metadata server for artworks and artists. He is presently in production of Magic, a project documenting innovation in humanities-centered interactive media, and USA Today, a multimedia project focusing on trans-nationalism's consequences. Craig is an Assistant Professor of Cinema Practice at USC's Institute for Multimedia Literacy, part of the School of Cinematic Arts, where he teaches project design and creative hypertext. He is also further immersed in network art and culture as a researcher at the University of Maine's Still Water lab". -- from Vectors, Volume 2, Issue 1, Fall 2006

1 COPY IN THE NEXT

Published in Fall, 2006 by Vectors in Volume 2, Issue 1.

This copy was given to the Electronic Literature Lab by Erik Loyer in November of 2021.

PUBLICATION TYPE

Online Journal

COPY MEDIA FORMAT

Web