Editor's Introduction

"Caught in the midst of an ongoing research project, I have logged many hours in the archives at the Library of Congress. To enter this archive is to enter a rarified space, a quiet zone accessed only with a special ID card and a trip through a metal detector. No pens are allowed and no paper. The histories collected here are special and guarded. They unfold for the scholar and the expert, for those with credentials. But what if we thought about the archive differently, as a place of open access and limited gatekeeping? Digital technologies can help animate the archive in meaningful ways, pointing toward new modes of memory and history that engage the spirit of open access and democratic exchange while also undertaking very crucial work in cultural preservation. The Hurricane Digital Memory Bank (HDMB) provides a vibrant model of just such an endeavor, functioning as a re-imagined archive, one conceived for the present and the future.

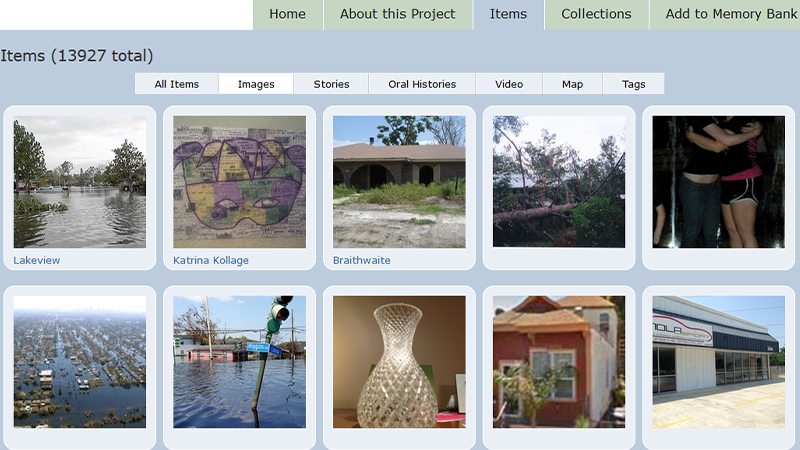

Over 500 images, numerous stories, and diverse other files – including podcasts, PDFs, and more – [that] chronicle the powerful storms that ravaged the Gulf Coast region in fall 2005 and document the experiences of those affected by the worst hurricane season in recorded history. As the user traverses the words and pictures gathered here, the human and material costs of the hurricanes come into more powerful relief, adding a new level of granularity, intimacy, and poignancy to mainstream media accounts. We know that Hurricane Katrina unleashed the largest displacement in U.S. history; HDMB layers that knowledge with detailed meanings and diverse voices. In my introduction to the second issue of Vectors, I commented on the limits of putting too much faith in technology when faced with a disaster like Katrina. HDMB suggests that technology can also help us connect, remember, and perhaps heal.

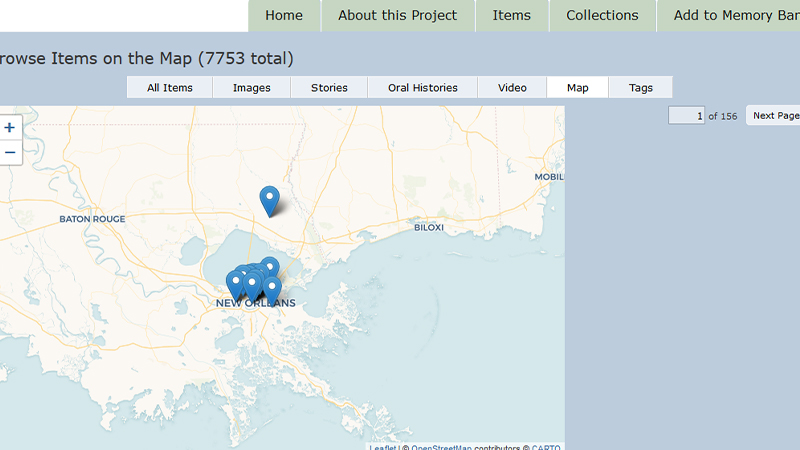

The website reconfigures the goals of traditional oral history projects via a meaningful collision with electronic media, creating a space not only for the preservation of memory and experience (a lofty aim in and of itself) but also for emergent modes of interpretation and knowledge management. For instance, the site's 'map browser' allows users to pinpoint the geographic location of a story or an image, while also inviting a comparative analysis of how different neighborhoods or regions were impacted. The site's search function allows this archive to respond to its viewers own interests and desires, while the 'contribute' field encourages additions and reflections, opening the collection up to expansion and growth. To date, many of the pieces published in Vectors in some way work as analogues to more traditional scholarly artifacts, re-making and re-imagining the article in rich multimedia dimensions or supplementing the constraints of the monograph via an expanded archive. Projects like this one push in another direction that the journal is eager to explore, toward a more connected and networked scholarly vernacular.

HDMB simultaneously displays and extends the pioneering work undertaken by the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University. Since the early 1990s, the Center has actively modeled vibrant new modes of public history while exploring the power of the internet to expand our conceptions of what counts in and as an archive. Their work troubles a number of binaries long reified by history scholars (and humanities scholars more generally), including one/many, closed/open, expert/amateur, scholarship/journalism, and research/pedagogy. We are pleased to feature their work here." -- Vectors Journal Editorial Staff, Vectors, Volume 2, Issue 1, Fall 2006

Producers' Statement

"In early January 2006 the New York Times released its list of the ten most read stories of 2005; six of them concerned Hurricane Katrina. Katrina stands as the worst natural disaster in U.S. history, by far the most expensive and one of the deadliest. Only the hurricanes in Galveston (1900) and Okeechobee (1928) killed more people. The storm displaced more than a million people and created an unprecedented humanitarian crisis that will not quickly subside. Hurricane Katrina was only one (albeit the most destructive) of fourteen hurricanes and twelve tropical storms that hit the United States (and the Caribbean) in 2005, the worst hurricane season ever recorded. Less than three weeks after Katrina, Hurricane Rita, an even more powerful storm and, indeed, the strongest hurricane ever in the Gulf of Mexico, struck Louisiana and Texas. Although Rita did not destroy refineries and ports in the Texas Gulf as originally feared, the storm still caused close to $10 billion in damages. Nearly one month later, Wilma became the third Category 5 hurricane of this disastrous season. Like prior catastrophes such as the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 and the great 1927 Mississippi Flood, the impact of these natural disasters continues to reverberate across the country.

How will the story of those storms be recorded and later told? How can we insure that the historical record is diverse and inclusive? The Hurricane Digital Memory Bank (HDMB) is one response to the effort to collect and preserve the social and human memory of these devastating storms. Organized by George Mason University's Center for History and New Media (CHNM) and the University of New Orleans (UNO) and funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Hurricane Digital Memory Bank (www.hurricanearchive.org) hopes to foster some positive legacies by allowing the people affected by these storms to tell their stories in their own words, which as part of the historical record will remain accessible to a wide audience for generations to come.

HDMB asks contributors to write first-hand accounts or anecdotes; to upload on-scene images, podcasts, or other born-digital files; or to copy blog postings or emails and and submit them to the archive. In addition, we ask contributors to provide the geographic coordinates of either their location before the hurricanes hit or the location that best represents the content of their submission by entering a zip code or street address. By dynamically combining this information and their contribution with Google Maps, we provide a visual way of browsing the archive that enables new kinds of research and connections to be made. Visitors can easily browse the contributions in a specific location (down to a specific street corner), or create a customized map that is populated solely by contributions that contain a certain keyword or type of object.

The project builds on prior work by the Center for History and New Media (with the support of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation) to collect and preserve history online through what we have begun to call 'digital memory banks,' including the Blackout History Project, the Echo project, and the September 11 Digital Archive. The latter project gathered more than 150,000 digital objects from tens of thousands of individual contributors and to date has been the single most successful effort to collect and preserve digital materials related to a historical event. As our own efforts expanded, others have launched projects in the online collecting of history. For example, the British Broadcasting Corporation's two-year online project to gather the stories of Britain's 15 World War II veterans and survivors of the London Blitz, entitled WW2 People's War, has collected more than 1,200 narratives. In the United States, the National Park Foundation, the National Park Service, and the Ford Motor Company are using the Internet to collect first-hand narratives of life during wartime for a planned Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond, California. Growing numbers of online collecting efforts have also emerged outside of formal institutional contexts. The photo sharing website, Flickr, for example, has become a place to document shared events as well as one's own life. HDMB stands as another example of how the Internet can promote democratic means for saving the digital record of significant events.

Our largest goals, then, are to both collect a rich and diverse record about the storms and their aftermath and to promote popular participation in presenting and preserving the past." -- Center for History and New Media, Vectors, Volume 2, Issue 1, Fall 2006

Project Credits

"Executive Producer: Roy Rosenzweig, Center for History and New Media (CHNM) at George Mason University (GMU)

Co-Director: Daniel Cohen, CHNM

Co-Director: Tom Scheinfeldt, CHNM

Project Manager: Sheila Brennan, CHNM

Director of Gulf Coast Outreach: Michael Mizell-Nelson, University of New Orleans

Technical Lead: Jim Safley, CHNM

Creative Lead: Nate Agrin, CHNM

Project Assistant: Olivia Ryan, CHNM

Project Assistant: Allison Meyer O'Connor, CHNM

Design Consultant: Stephanie Hurter, CHNM

Sponsoring Institutions: George Mason University and University of New Orleans

Funding provided by Alfred P. Sloan Foundation

Partners: Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History; NewsHour with Jim Lehrer; Louisiana State Museum; The New Orleans Oral History Project;

Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities; University of Southern Mississippi; Mississippi Humanities Council; University of Southern Mississippi's Center for Oral History and Cultural Heritage; Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College; Museum of the Gulf Coast — Center for History and New Media, May 19th, 2008

Center for History and New Media

Producer

Since 1994, the Center for History and New Media at George Mason University has used digital media and computer technology to democratize history — to incorporate multiple voices, reach diverse audiences, and encourage popular participation in presenting and preserving the past. CHNM combines cutting edge digital media with the latest and best historical scholarship to promote an inclusive and democratic understanding of the past as well as a broad historical literacy. We sponsor more than a dozen digital history projects and offer free tools and resources for historians. CHNM's work has been recognized with major awards and grants from the American Historical Association, the National Humanities Center, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Department of Education, the Library of Congress, and the Sloan, Hewlett, Rockefeller, Gould, Delmas, and Kellogg foundations." -- Vectors, Volume 2, Issue 1, Fall 2006

1 COPY IN THE NEXT

Published in Fall, 2006 by Vectors in Volume 2, Issue 1.

This copy was given to the Electronic Literature Lab by Erik Loyer in November of 2021.

PUBLICATION TYPE

Online Journal

COPY MEDIA FORMAT

Web