Overview

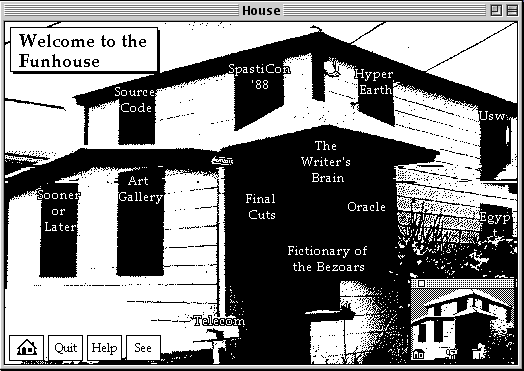

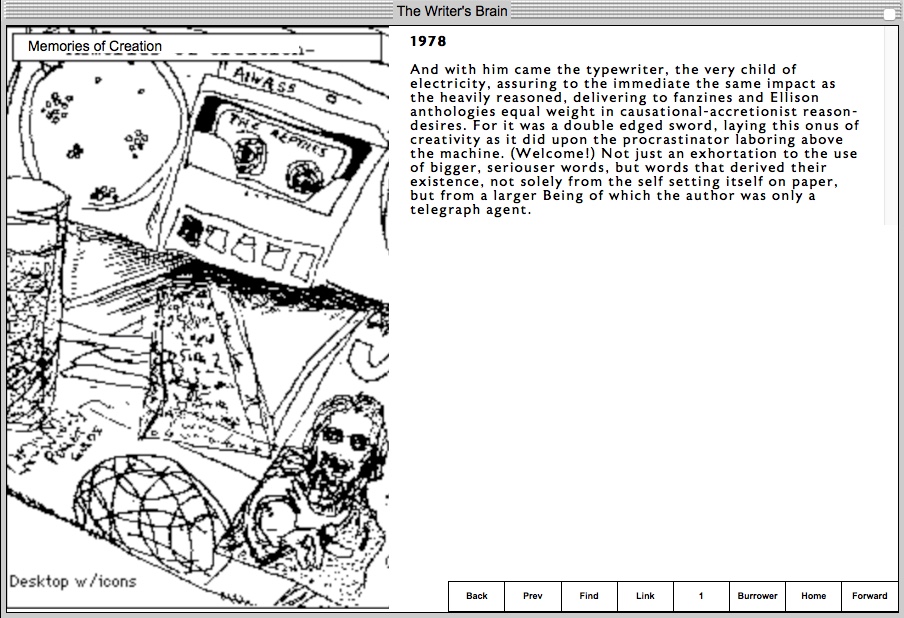

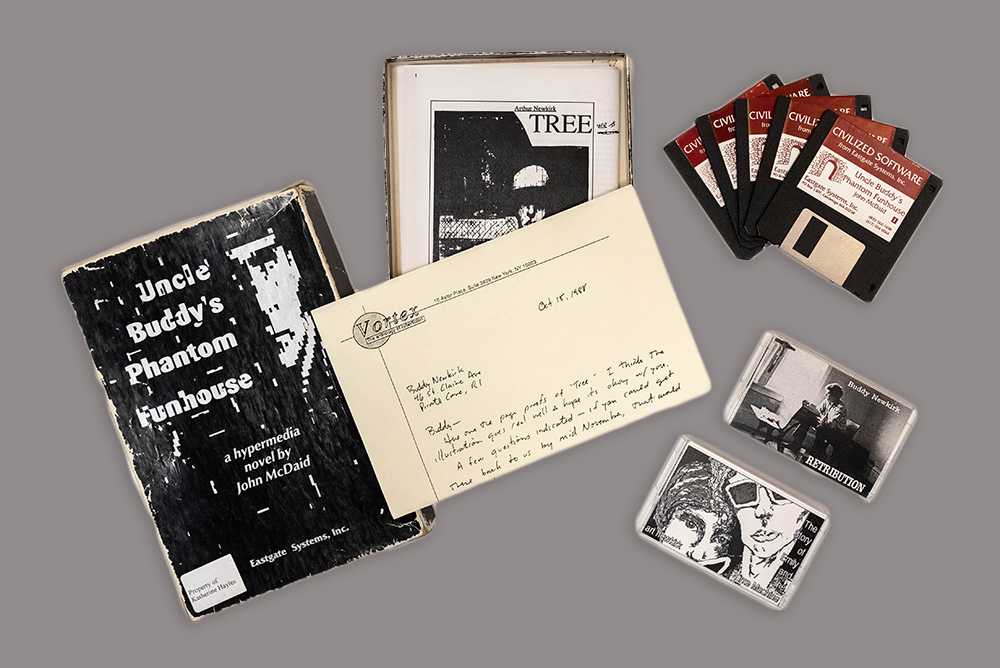

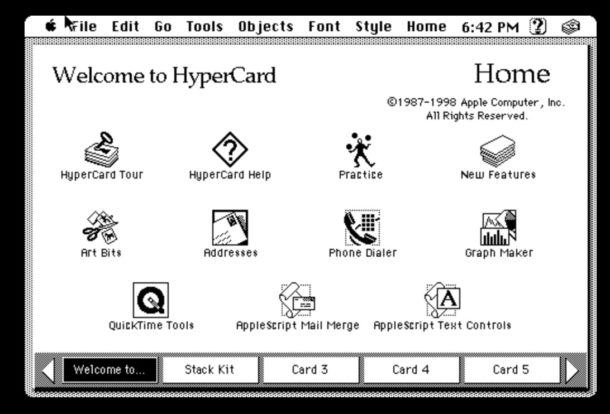

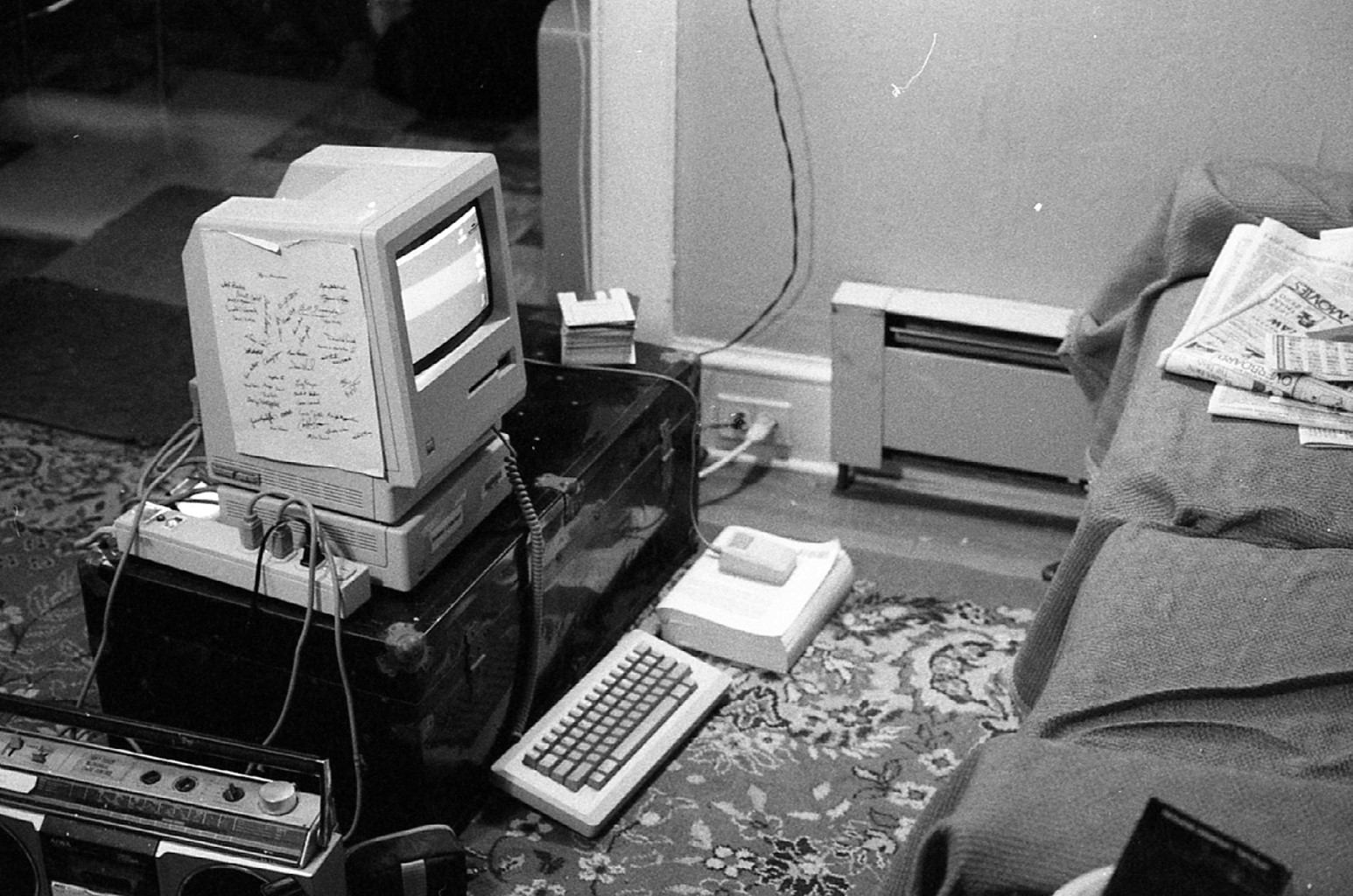

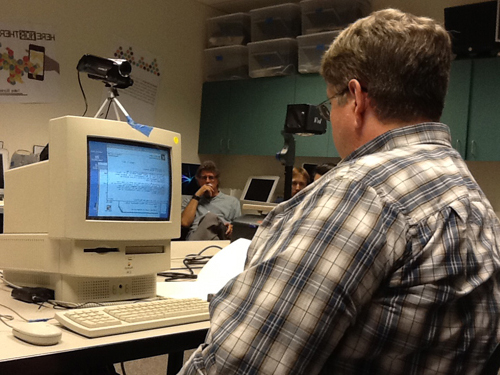

Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse, created by science fiction writer John McDaid, is a hypermedia novel and game built on the HyperCard 2.0 platform and published by Eastgate Systems, Inc. in 1992/93. Unlike works of other hypertext literature the company released, Funhouse was distributed in a box containing five 3.5-inch floppy disks, two musical cassette tapes, page proofs of a short story written by Arthur Newkirk entitled “Tree,” and a letter from an editor of Vortex magazine to Buddy Newkirk about the page proofs. At the heart of the story is a mystery: All of these artifacts comprise what is left of the literary estate of Arthur “Buddy” Newkirk. You, the reader, are left to solve the mystery of who “Uncle Buddy” is and what happened to him––and you must sleuth through the digital funhouse on your computer screen and physical artifacts you hold in your hands to answer these questions.

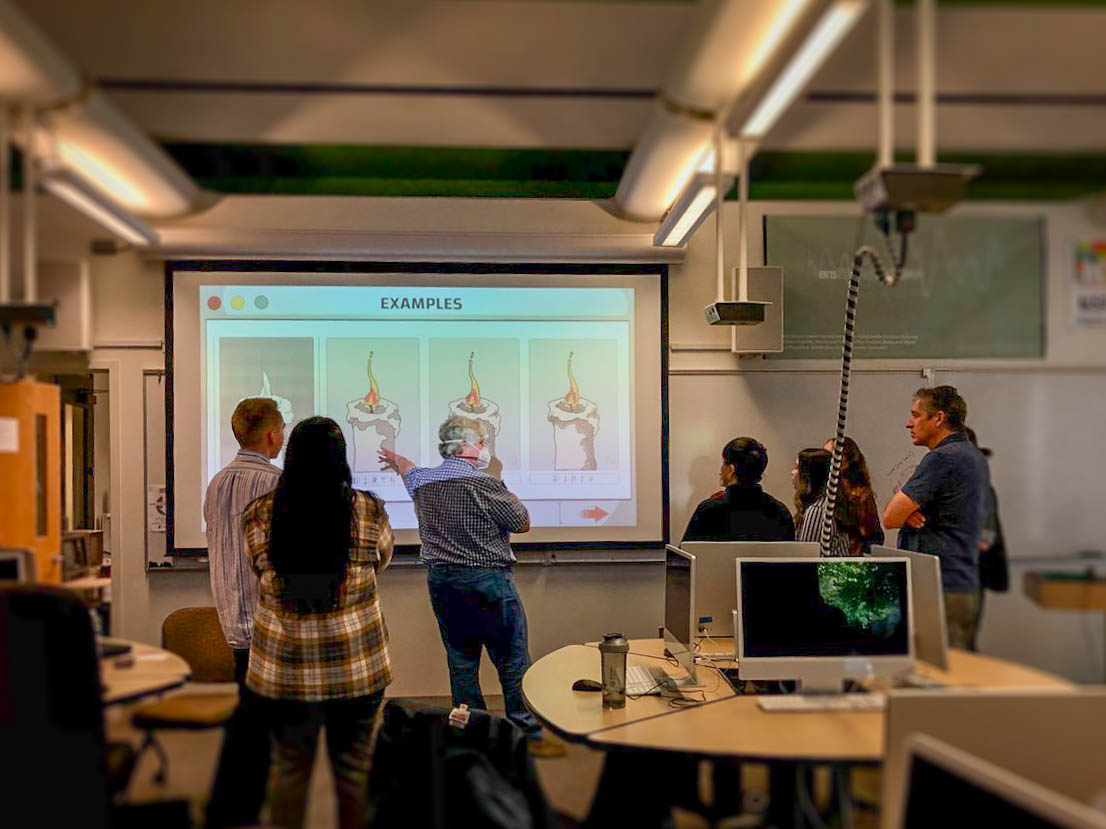

An instant cult classic, Funhouse was reviewed in The Village Voice by Gavin Edwards, regular contributor to Rolling Stone and Spin. It was also mentioned by Robert Coover in his controversial “End of Books” front-page essay in the New York Times Book Review in 1993 and later was the subject of the critic’s longer account of the work in the Times. It was a favorite of noted media theorists including N. Katherine Hayles, Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Jill Walker Rettberg, Astrid Ensslin, Loss Pequeno Glazier, Alvaro Seica, and Roberto Simanowski and was one of the four works discussed in Stuart Moulthrop and Dene Grigar’s Pathfinders project and their book, Traversals: The Use of Preservation for Early Electronic Writing for The MIT Press (2017).