everywhere a sign

Semiotics

Our first reading is chapter 2, “Signs” from Daniel Chandler’s Semiotics for Beginners. Here, Chandler introduces readers to the two men regarded as the founders of semiotics and their different accounts of how signs work.

So you’re walking home one day when you see a sign in the yard across the street with a drawing of what you recognize as a cantaloupe, and below that, a drawing of what looks to be a one dollar bill. It just so happens that you’re hungry, you’ve  been craving cantaloupe all day and you have some money in your pocket. You cross the street to buy a big, ripe cantaloupe to take home. You walk a couple of more blocks thinking about the cantaloupe you are going to eat when you get home, making yourself even hungrier. You turn a corner, and in the yard beside you is a sign bearing the markings “Cheeseburgers $3.00”. By now you are starving and you still have a long walk ahead of you, so you buy the burger and eat it there on the spot.

been craving cantaloupe all day and you have some money in your pocket. You cross the street to buy a big, ripe cantaloupe to take home. You walk a couple of more blocks thinking about the cantaloupe you are going to eat when you get home, making yourself even hungrier. You turn a corner, and in the yard beside you is a sign bearing the markings “Cheeseburgers $3.00”. By now you are starving and you still have a long walk ahead of you, so you buy the burger and eat it there on the spot.

The question is, how did you know that you would be able to buy cantaloupe and cheeseburgers on the front lawns of random strangers? You did not see either of these foods when you looked at the signs. You did, however, see representations of these foods. That is what signs are; they representations of other things or ideas. The image in the first sign represented cantaloupe by resembling what you understand to be a cantaloupe. You recognized the markings on the second sign as symbols that you have learned represent a cheeseburger, as well as certain sounds that also represent a cheeseburger.  Another way to think of signs is as directional road signs. Signs point your mind towards a certain thought.

Another way to think of signs is as directional road signs. Signs point your mind towards a certain thought.

Around the turn of the 19th/20th centuries, language scholars started describing language as a system of signs, forming an area of study that we now call semiotics. The Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure envisioned the sign as having two inseparable components, the signifier and the signified. He defined the signifier as a “sound pattern” You can think of a sound pattern as a word that you think in your mind. You do not actually hear the word because it has no sound. However, its “pattern” is identical to what you would hear if someone spoke the word to you. The signified is the thought or concept that is associated with that sound pattern. For example, if you think the word banana, you will, at the exact same time, think about something else. Probably a banana. Saussure compares the relation between the signifier and signified to that between the two sides of a piece of paper. It is possible to talk about the qualities of each separately, but the two are inseparable. You can never have a signifier without a signified and vice versa. You cannot think the word “banana” without whatever thoughts you associate with that word, just like you can not think about a banana without also thinking whatever word that you associate with bananas.

If this all seems a little confusing, that probably means that you’re paying attention. Saussure’s model of the sign is so confining and unintuitive, that even he often failed to write about signs in terms that did not contradict his model. In the story given above, it would seem natural to identify the signified with the drawing of a cantaloupe and the signified as the cantaloupe itself. However, both elements of Saussure’s sign only exist in the mind. It seems that Sasssure’s signs are isolated from the external world. However, Saussure often writes about objects in the external world in as if they are signifiers. It is almost impossible not to. If we are not looking at how signs relate to a shared, external world, than what is the point? The benefit of a science like semiotics is the insight it gives us into how we understand and interact with the world.

However, Saussure did have strong reasons for restricting signs to internal thought. We can see why signifieds are associated with thought instead of things in the outside world by considering the fact that, if I perceive something that signifies, for me, a koala bear, a koala does not instantly appear in front of me; nor am I instantly transported or even directed to the nearest one. The signifier leads to a thought of a koala bear, not the koala bear itself. A case can also be made for identifying the signifier with thoughts as well. When you see the symbols “pineapple”, there is nothing about the construction of the symbols themselves that directs you to a thought about the fruit. If there was, than they would do so for everyone, even people who do not understand English and/or cannot read. You may reply that the symbols would not signify a pineapple for these people simply because they do not understand the symbols. This suggests, however, that there is something in between (call it understanding, interpretation or, if you are Saussure, a sound pattern) the sensory perception and the thought that is signified. This “something in between” is Saussure’s signifier. (By the way, while thinking about sound patterns as words in your head is a useful way to start imagining Saussure’s conception of the signifier, it begs the question of what constitutes a “sound pattern” for people born  without hearing. Studies have shown that people who have grown up with ASL and have never heard words think in ASL gestures. It is probably more accurate to think of the signifier as the understanding or interpretation between the sensory perception and the signified that takes place when your think the word.)

without hearing. Studies have shown that people who have grown up with ASL and have never heard words think in ASL gestures. It is probably more accurate to think of the signifier as the understanding or interpretation between the sensory perception and the signified that takes place when your think the word.)

Saussure alludes to this last point when he contends that the sign itself is arbitrary. By this he means that there is never a necessary connection between the signifier and the thing signified. (This is a good example of where he seems to contradict his own model of the sign.) For example, there is no natural relationship between the sound I make when I say the word “banana” and an actual banana. There is nothing banana-ish about the sound of the word banana. Likewise, there is no natural relationship between the string of symbols “banana” and an actual banana, or even a natural relationship between those symbols and the sound of the word.

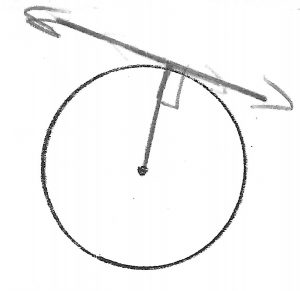

Around the time that Saussure was developing his science of the sign in Europe, C.S. Pierce was pioneering his version of semiotics in the United States. One important difference between Saussure’s and Pierce’s portrayals of the sign is that Saussure saw the sign as a structure, while Pierce was more interested in signification as a process. This process has three parts, the representamen, the interpretant, and the object. The representamen is that which represents. In the earlier example, this would be the drawing of the cantaloupe. The representamen is often referred to, even by Pierce, as the sign. Chandler states that the representamen is similar in meaning to Saussure’s signifier while the interpretant is similar to the signified. However, it may make more sense to say that the interpretant shares similarities with both the signifier and signified. It is similar to the former in the sense that it involves the act of understanding or interpreting the representamen, and to the latter in also being the corresponding thought. The object is that which is represented by the representamen. By allowing (but not requiring) both the representamen (I can understand why Pierce and Chandler usually just refer to the representamen simply as the sign, it’s a ridiculous word to have to write (and read) over and over) and the object to be material objects, Pierce connected the process of signification (semiosis) with the material world. It is important to note that neither the sign (representamen) nor the object have to be material. Think about how one thought can lead to another. For example in the cheeseburger story, your thought about a cheeseburger might lead you to wonder about the food safety laws in that part of town. In this case, the thought of the cheeseburger is both an interpretent in relation the symbols you saw in the front lawn, and also a sign in relation to another interpretant (thoughts about the food safety laws). The object can be immaterial (freedom) or even non-existant (Pegasus).

Pierce also addressed the idea of the arbitrariness of the sign. However, he recognized that some signs are less arbitrary than others. There is some natural relationship between the image of a cantaloupe and an actual cantaloupe. Assuming the drawing is accurate enough, it would be a sign for a cantaloupe to anyone who had ever seen a cantaloupe, regardless of their language and culture. Pierce suggested that there are three modes of representation. Each mode defines how a sign represents an object, and indicates how arbitrary that representation is. A sign is in the iconic mode (an icon) when it represents by its resemblance to what is signified. The drawing of the cantaloupe is an iconic sign for a cantaloupe. Signs representing in the symbolic mode (symbols) do so by convention. The signify something because we agree, or have been taught, that they do. Writing and spoken words (except perhaps for onomatopoeia) are great examples of symbols. Symbols generally have the most arbitrary relationship to the things they represent. Finally, signs in the indexical mode (indexes) represent when they are perceived as direct evidence of what is represented. Smoke is an index for fire and footprints are indexes of feet. Indexes are generally less arbitrary than either of the other two modes.

Chandler ends the chapter discussing the nature of meaning and its relationship to mediums. In both Saussure’s and Pierce’s models, meaning is a function of our understanding, not of the the images we see or symbols we read. At the same time, the medium through which we perceive those images or symbols may influence the meaning we find. We will explore both of these ideas throughout the semester.

Reading for August 31

“Signs”, Chapter 2 of Semiotics for Beginners / Daniel Chandler

Discussion Questions

- What does Chandler mean when he states that Saussure’s sign is structural and relational rather than referential?

- What does it mean to say that the signified has primacy over the signifier and vice versa?

- Do you agree with Saussure that the sign is arbitrary?

- What does Chandler mean when he writes that there are no natural concepts or categories reflected in language?

- What is the difference between the idea of a sign being ontologically arbitrary and socially arbitrary?

- How does Peirce’s model of the sign differ from Saussure’s?

- Where do you believe meaning resides, within the sign or within its interpretation?

- Give an example of a sign in the symbolic, iconic, and indexical modes?

- Why are there no “pure” icons?

- How have linguistics signs (possible) evolved from indexicals to icons to symbols?

Suggested Readings/Videos

Other chapters in Semiotics for Beginners.

“Nature of the Linguistic Sign” / Emile Benveniste

“Arbitrary Nature of the Linguistic Sign” / Manfu Duan

6 Responses to everywhere a sign

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Archives

Categories

Course Calendar

test comment

Your site visitors, especially me appreciate the time and effort you have spent to put this information together. Here is my website YW9 for something more enlightening posts about Thai-Massage.

Thank you for sharing your precious knowledge. Just the right information I needed. By the way, check out my website at FQ6 about Cosmetics.

For anyone who hopes to find valuable information on that topic, right here is the perfect blog I would highly recommend. Feel free to visit my site Article World for additional resources about SEO.

Superb and well-thought-out content! If you need some information about SEO, then have a look at Article Sphere

Your ideas absolutely shows this site could easily be one of the bests in its niche. Drop by my website QN5 for some fresh takes about Cosmetics. Also, I look forward to your new updates.