Fixsel

PIs: Matt Ratto and ginger coons, Critical Making Lab, University of Toronto

Collaborators: Isaac Record, Antonio Gamba-Bari, Dan Southwick

Funding: Canada Foundation for Innovation, Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, and Humlab, University of Umea.

Site: https://github.com/mattratto/experiences (umea20130)

Brief Note on Critical Making

I originally coined the term ‘critical making’ in work published in 2009 where I rather naïvely attempted to instantiate/describe a hybrid material-conceptual practice aimed at deepening and extending critical reflections on the material semiotic nature of technology. Since then I have continued to develop critical making practices and joint experiences and to publish my thoughts on the processes and results. I have two specific aims; first, to convey what I have learned from my own critical making experiences; and second, to try and encourage other scholars in the social sciences and humanities to take up making as an intrinsic aspect of their own critical scholarly practice. It is obvious from the increasing take up of ‘making’ as a trope within the digital humanities and other fields that either I have been successful in this regard or, more likely, I simply picked up on the value of material engagements slightly sooner than other scholars with similar critical interests.

I continue to believe that critical making is something that must be experienced – it is not enough to simply think about or witness the results of others. Equally, I believe that it is not enough to simply make – one must also try to expose the conceptual and critical processes (and not just the results) through whatever means necessary. This can and should include documentary traces such as video recording, still images, and textual descriptions but, at least for academic makers, should also include scholarly writing as a vehicle for communication with its own specific affordances and capabilities. It is not easy to be a critical academic maker given the conjoined needs for conceptual as well as technical forms of expertise. But I continue to believe that it is precisely this hybrid identity that offers the most rewards for scholars interested in both activating and extending past and current theories regarding materiality and the complex phenomena that marks the socio-technical world.

Overview of Fixsel workshop

The law and other formal and informal entities are used to treating ‘the digital’ and ‘the physical’ as two entirely separate worlds. We have been encouraged to think this way by a variety of public and private interests, including both libertarian (e.g. John Perry Barlow’s famous ‘Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace’) and conservative voices (e.g. reasoning regarding the DMCA in the US,) depending on need. Over the last few decades, much labor has been spent to encourage the idea that information is immaterial, that form and content can be separated, that the medium is just a neutral channel for transmission.

The digital humanities was quick to pounce on the fallacy of the immateriality of information, with scholars such as Katherine Hayles, Joanna Drucker, and Matthew Kirschenbaum (among others) pointing out the political and social issues engendered by such a belief. Drawing upon feminist scholarship including the work of Donna Haraway, Hayles (1993,1999) highlighted the ways arguments about the immateriality of information worked to efface the embodied nature of human experience. Similarly, Drucker has described the ascension of ‘mathesis’, (2009) the prevalence of numerical logic that articulates the social and the political through the lens of quantifiable logics with an attendant focus on rationality and instrumentality. Matthew Kirshenbaum has noted that “computers are unique in the history of writing technologies in that they present a pre-meditated material environment built and engineered to propagate an illusion of immateriality”.

Details

The fixsel workshop serves as a simple, participatory way to guide reflection regarding the specific materialities of digital images. Using pre-made materials including a pre-programmed ATTiny 85 microcontroller, a printed paper template, an RGB LED, copper tape and other supplies, participants construct their own ‘physical pixel.’

Participants are then asked to collectively reproduce an image projected on a screen by matching their pixel to one of pixels of the projected image. These pixels are then arranged next to the projected image and participants are asked two specific questions: 1)How does the physical pixel version differ from the projected image version? What is conserved between the two images?

Conceptually, the participants are supported in their reflections by quotes and theories drawn from the work of the above scholars. In particular, Kirschenbaum’s conceptual framing of the digital as including both ‘forensic’ and ‘formal’ materiality is used to guide and deepen initial thoughts. The image chosen to be projected is Frederich Schinkel’s “The Invention of Drawing” as described in Joanna Drucker’s book Speclab. (see below)

Living Lightning

PI: Andrew Quitmeyer, Georgia Institute of Technology

Collaborators: Peter Marting, Antonia Hubancheva, Daniëlle Hoogendijk, Susanne Wiesner, Julia Legeli, Holland Galante, Barrett Klein, Ashley Scuderi, Gabriel Peterson, Noel Juvigny-Khenafou, Ming Guo, Veronica Sinotte, Liz Joyce, Michelle Marie

Funding: Short-Term Fellowship, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute Panama

My PhD research in Digital Naturalism, investigates the role of technology in in animal behavioral field studies. To empower new research, I combine theory and practices in the fields of Digital Media and Ethology via critical approaches to uncover cultural, technological, and biological factors shaping scientific practices.

While the foreignness of animals’ experiences necessitates the use of supplemental instruments like digital sensors and probes, the expense and complexity of some devices can steer researchers in erroneous directions. One scientist-participant in my research notes that “[many] experiments are designed around the set-up rather than the questions, and [this] limits the type of questions that we ask.” Digital Naturalism explores Critical Making approaches to tackle these technological concerns directly.

Based on Ratto’s original paper [1], I launched projects like “Living Lightning” at a field station in Panama to teach both electronics skills and critical reflection. A chance jungle encounter with gargantuan lightning beetles inspired my design of a workshop that would simultaneously let participants understand the basics of digital sensing and acting, while also exploring the fireflies’ strange rituals first-hand.

Participants built and programmed their own wearable firefly costumes from materials including cardboard, LED’s, copper tape, and inexpensive ATTiny85 microcontrollers. At each step of their design, participants “purchased” components by receiving different reflective prompts on which they were asked to meditate. In parallel with the building process itself, questions such as “What part of your tool can tell a lie?” prompted critical analysis and discussion of the technological, biotic, social, and environmental structures pervading this project and their research. The costumes were then worn into the fireflies’ natural habitat, as we performed embodied simulations of their mating rituals.

Consulting local firefly expert, Fred Vencl, helped us initially design the costumes’ flashing patterns and script our performance, but the construction and performance were necessary for obtaining deeper understandings. One of Critical Making’s other pioneers, Garnet Hertz, states, “doing something yourself, as a non-expert, is the fastest way to unpack and learn about the things that would normally remain invisible and taken for granted” [2]. In the workshop, our hybrid making-discussing brought up concepts about the scientists’ other tools, social origins of digital devices, funding issues, and the basic factors (such as faulty soldering) which can manipulate “truth.” Performing the devices in the wild with each other and with the fireflies themselves spurred iterative reflection on our designs and how they revealed or ignored certain attributes of the environment or the insects. Critical Making’s hybrid material-analytical process incorporating technological, social, and biological factors provided insights beyond research with fireflies, and helped form a powerful framework for scientists to develop and understand their own research tools.

Captain Chronomek

PIs: Theresa Tanenbaum, Simon Fraser University; Karen Tanenbaum, UC Santa Cruz

Collaborators: Allen Bevans, Electronic Arts; Jim Bizzocchi, Alissa Antle, Ron Wakkary, and Audrey Desjardins, Simon Fraser U; Amanda Williams, Fabule Fabrications and Wyld Collective; Kate Compton, UC Santa Cruz

Awards: Best Costume at Vancouver Maker Faire, Featured in the “Powered by Fiction” exhibit at the 2012 Emerge Conference at ASU

Site: http://tf.thegeekmovement.com/wp/?page_id=40

Steampunk imagines a fictional history for technology dominated by Victorian aesthetics, engineering, materials, and techniques (Onion, 2008). It is rooted in a number of cultural expressions including its own literary canon, music scene, and fashion sensibility. However, it is the centrality of maker practice within the Steampunk community and its highly politicized and ideological negotiations of post-modern and Victorian values that make the subculture so interesting. As a critical making practice, Steampunk draws on utopianist design fictions (Bleecker, 2009; Sterling, 2009)from its literary cannon and a political ethos grounded in punk attitudes (Carrott & Johnson, 2013) to imaginatively remediate contemporary technologies (Tanenbaum, Tanenbaum, & Wakkary, 2012).

As part of our critical making practice, we developed a character called “Captain Chronomek”, a time-traveling Steampunk superhero who himself has a maker/tinkerer bent. The genesis for Captain Chronomek was a superhero-themed student design competition at the Tangible, Embedded and Embodied Interaction Conference (TEI) in 2011. Chronomek is a man out of time, a Victorian-era mechanic pulled from his own period and granted time-traveling powers. With access to technology from across all of time, Chronomek is the ultimate maker/hacker, cobbling together what he needs from all of human (and even non-human) history. In this way, Chronomek encapsulates the dual fascinations of the Steampunk movement: the romanticized past and the never-quite-realized utopian future.

The design process for creating the character was one of continual iteration between the concept and the physical artifacts; the character was shaped by the technology and material we had on hand. A feedback loop was established between the physical creation, the theoretical explorations of Steampunk practice and design fiction, and the ideation around the fictional world. From a methodological standpoint, this type of Critical Making owes much to the epistemological practices employed in contemporary arts and practice-as-research (Nelson, 2006).

Steampunk reacts against the rise of minimalist “flat” industrial design in hardware and software by returning to the brass, leather, and wood handcrafted materials of the past; it resists the proliferation of “black box” technologies and closed systems by exposing technology as an aesthetic element in its own right. We see within Steampunk subculture the perception of an impending “crisis” for late-stage capitalist and industrial societies, beyond which it is difficult to perceive a stable future. This is one of the core contradictions that underlies the ideology of Steampunk: although the genre celebrates an era in which mass production and assembly were coming of age, it resists traditional narratives of industrialization that prize uniformity and homogeneity (Tanenbaum, Desjardins, & Tanenbaum, 2013).

Bleecker, J. (2009). Design Fiction: A Short Essay on Design, Science, Fact and Fiction (Vol. 2011).

Carrott, J., & Johnson, B. D. (2013). Vintage Tomorrows: A Historian and a Futurist Journey Through Steampunk into the Future of Technology. O’Reilly.

Nelson, R. (2006). Practice-as-research and the Problem of Knowledge. Performance Research, 11(4), 105–116.

Onion, R. (2008). Reclaiming the Machine: An Introductory Look at Steampunk in Everyday Practice. The Journal of Neo-Victorian Studies, 1(1), 138–163.

Sterling, B. (2009). The User’s Guide to Steampunk. Steampunk Magazine, 1(5), 30–33.

Tanenbaum, T. J., Desjardins, A., & Tanenbaum, K. (2013). Steampunking Interaction Design: Principles for Envisioning Through Imaginitive Practice. Interactions, 20(3), 28–33.

Tanenbaum, T. J., Tanenbaum, K., & Wakkary, R. (2012). Steampunk as Design Fiction. In CHI 2012 (pp. 1583–1592). Austin, Texas: ACM Press.

I ♥ E-Poetry

PI: Leonardo Flores, University of Puerto Rico

Collaborators: Hannelen Leirvag, Cynthia Román, Ian Rolón, Bárbara Bordalejo, Samira Nadkarni, and Luís Claudio Fajardo

Advisory Board: Kathi Inman Berens, Alan Bigelow, and Mark C. Marino

Funding: NEH Collaborative Research Grant (Under Review)

Site: http://iloveepoetry.com

This scholarly blog was launched on December 19, 2011 as a constraint to read and critically reflect upon a work of e-poetry every day, leading me to revisit known works, discover new ones, and expand my knowledge of this emergent poetic genre. Its initial performance was a continuous run of 500 daily entries, completed on May 2, 2013. What started as a personal project rapidly developed an audience, led to publication opportunities, formed partnerships, received a DH Awards nomination resulting in 1st runner up honors, and attracted international attention. In order to best serve its growing audience, I created an Advisory Board and their ideas, guidance, perspective led to a reconceptualization of the project, opening it up to other genres of electronic literature, inviting collaboration and guest contributions through various CFP, and freeing me from daily writing to take on a more editorial role in its production.

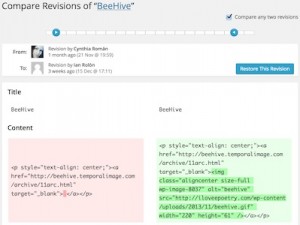

I call this reconceptualization phase 2 of the project (officially launched in September 2013) which invites members from the community, including students, to submit entries to respond to several wide open calls for postings (CFPs). From a single-scholar artisanal production, it has grown into a team effort with the addition of three contributors. I also have interns– students who enroll every semester with me in a Digital Humanities Internship course and carry out many activities, such as tagging, reshaping interfaces, correcting link structures, and creating resources for the study of specific genres, publications, and exhibitions. Their activities are documented in the Flores y Compañía site: http://leonardoflores.net/lab.

All these activities happen with zero budget, or rather a minimal investment from my own finances as I pay for private Web hosting and a domain name. Last academic year, I benefitted from being a Fulbright Scholar at University of Bergen and having students volunteer to work on my project. This academic year, as I returned to my home institution, I have competed for and won research release time and seed money to purchase equipment and software to continue these activities. On December 27, 2013 I submitted an NEH Collaborative Research Grants proposal to bring together a team of 19 scholars to collaboratively write 530 I ♥ E-Poetry entries and a book manuscript in a 3-year period. The book would be tentatively titled “A World of E-Literature” and would feature e-lit from Africa, and e-lit produced in several languages: English, Spanish, Russian, Polish, Italian, French, and German. If awarded, the grant would provide travel funding and modest stipends for all participants, starting on January 2015.

All this work has been informed by several critical theories, drawn from literary criticism, new media theories, textual scholarship, and the digital humanities. The practice of close reading updated by N. Katherine Hayles’ notion of media-specific analysis is foundational to I ♥ E-Poetry’s methods, as are platform, software, and critical code studies. The e-lit works reviewed are tagged with a typology of textual behavior I created, informed by the work of textual scholars such as Jerome McGann, Peter Shillingsburg, Johanna Drucker, and John Bryant. I ♥ E-Poetry has recently joined the ELO’s Consortium of Electronic Literature (CELL), which seeks to bring together international databases with a global search engine, develop metadata standards, a common taxonomy to describe the works, and maximize interoperability between resources.

I ♥ E-Poetry is critical making: it’s activities have become a starting point for presentations, critical writing, and creative writing (such as my Taroko Gorge remix TransmoGrify).

The Story in Wood

PI: T. Hugh Crawford, Georgia Institute of Technology

Collaborators: Sarah Dennis, Matt Berens, Shelby White, Andrew Bassett, Itje Okafor, Troy Kleber, Weatherly Langset, John Umberger, Ben Ashby, Albert Shaw, Kale Brown, Megan Fechter, Walter Ley, Zachery Butner, Abhinya Uthayakumar, Sarah Tropper, Brian J. Shin, Olivia Lodise, Ariel Santillan, Dina Mengesha, Georgia Tech

Site: http://thestoryinwood.org

The “Story in Wood” helps students encounter first-hand the Heideggearian distinction between tools ready-to-hand and those present-to-hand, and at the same time enables an exploration of the relationship between modeling, material, and knowledge production. Mediated through readings of Heidegger, Charles Keller, Matthew Crawford, Tim Ingold, along with the history of wood construction in the US, and coupled with plans drawn, coded, and CADed (Computer-Aided Design), this project explores the movement from paper to pixel to model, to wood (and back). The goal was to help students understand the complexity that making entails but also to build on the learning that making produces.

The term “Useless Design” designates a pedagogical practice where the designed product has little or no economic or instrumental value, and the primary skills involved in its production will not likely be useful in a student’s academic or professional career. Learning the basics of timber framing does not generally lead to professionally useful skills for the college graduate. Useless design helps students slow down, focus on and articulate both the familiar and the unfamiliar parts of making. Useless practices prompt naive questioning that probes historical circumstances and social norms. By recasting technology as a set of practices that must be learned and articulated through an historically sedimented space, this project foregrounds making as a process that draws across many disciplines and blurs most of those disciplinary boundaries.

The “Story in Wood” began with a series of readings on wood and material culture. Then, the students chose to collaborate on a project focusing on the history of building practices, skill acquisition, and the role of modeling in producing knowledge. This project asked them to construct three “bents,” or slices of a building that can be assembled as a small structure. The students formed three teams: one researched nineteenth-century building and made a timber-framed bent, one looked at twentieth-century building with dimensional lumber, and the last examined twenty-first century building with plywood slot and tab techniques cut out on a large CNC (Computer-Numerical Control) machine. Although the structure of each project was of interest, I was more interested in process. Students drew plans by hand, CADed, 3d-printed, and laser cut small scale models. They also questioned each step of the process, researched the history of those processes, discussed at length any design proposal, and constantly reframed all forms of mediation. We learned that all materials — wood, 3d printing plastic, pictures, words — are recalcitrant, and that making involved both the design of objects and the design of learning.

#nextchapter

PIs: Students in the Creative Media & Digital Culture Program; Dr. Dene Grigar & Vancouver City Councilman Jack Burkman, Advisors;

Funding: $38K from Washington State University; theCougParents Fund; Comcast; Fort Vancouver Regional Library District; Clark College; City of Vancouver; Columbian Newspaper; the Community Foundation for Southwest Washington; Vancouver School District; Evergreen School District; Schwabe, Williamson, & Wyatt; AHA!; BergerABAM; Heathman Lodge; and Adco.

Awards: Washington State University Vancouver, “2013 Undergraduate Research Award.”

Site: http://hashnextchapter.com

#nextchapter is a media literacy initiative aimed at preparing the Vancouver, WA community for a growing knowledge-based economy. Envisioned as a 3-year pilot project with the potential for long term presence in the city, #nextchapter was devised by the faculty in the Creative Media & Digital Culture (CMDC) program in the summer 2012. The project was formally adopted by Washington State University Vancouver, City of Vancouver, other local stakeholders and received strong support from 17 different sponsors, including the Fort Vancouver Regional Library, the Friends of the Vancouver Community Library, Internet Essentials by Comcast, WSU Foundation CougParent Fund, Clark College, Vancouver Public Schools, Evergreen Public Schools, the Community Foundation of Southwest Washington, Schwabe, Williamson & Wyatt, BergerABAM, AHA!, and The Columbian newspaper.

Year One of #nextchapter focused on the theme of “digital ethics” and made the book, Program or Be Programmed by noted internet pioneer Douglas Rushkoff the center of study. To that end, 1000 books were purchased and distributed for free to the public, and Rushkoff was brought Vancouver for a series of free public lectures that offered insights into issues raised in the book. The project also offered a free workshop series that provided instruction in using social media, programming, implementing SEO, utilizing mobile media, and other topics. Reading forums, both online and face to face, were created to provide readers with the opportunity to talk about the material in the book and issues they face with using and understanding digital media. All of these events were developed and managed by the students and faculty of the CMDC program. Students in the program’s Senior Seminar course (DTC 497), led by Grigar, were responsible for producing all of the digital assets for the project, including the website, forums, YouTube videos, and social media content and strategy. They also handled all of the multimedia design that was also used for print promotional materials.

Year Two, now underway, has received the same strong support from sponsors and the community. The theme is “digital learning,” and the book selected is Cathy Davidson’s Now You See It. Plans to bring Davidson to Vancouver and WSUV in the spring for public lectures are underway. In addition to the free public lectures and workshops, a film festival is also planned. The theme for Year Three is “digital democracy.”

Fort Vancouver Mobile

PIs: Drs. Brett Oppegaard & Dene Grigar, The Creative Media & Digital Culture Program, Washington State University Vancouver

Funding: 2012 We the People Grant, National Endowment for the Humanities; Start-Up Grant, Office of Digital Humanities; 2011 National Endowment for the Humanities; 2011 and 2010 Clark County Historic Promotions Grant; 2010 WSUV Research Mini-Grant

Awards: 2013 John Wesley Powell Prize for outstanding achievement in historical displays; 2013 Historic Preservation Officer’s Award for media, from the Washington State Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation; National Park Service’s George and Helen Hartzog Award for Outstanding Volunteer Service for research at Fort Vancouver

Site: http://fortvancouvermobilesubrosa.blogspot.com

Fort Vancouver Mobile is a ground-breaking mobile app, created for the Fort Vancouver National Historic Site and funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities with a $50,000 Digital Start-Up Grant awarded to Dr. Dene Grigar and Professor Brett Oppegaard. A collaboration among many partners, including the historic site staff and volunteers; new media scholars and students at Washington State University Vancouver, Texas Tech University and Portland State University; and several regional media and web development professionals, the project has received other developmental funding from the Clark County Commissioners, via the Historical Promotion Grant program, as well as seed grants from Washington State University Vancouver as well as the college’s Creative Media and Digital Culture program.

The Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, which attracts more than 1 million annual visitors to its Vancouver campus, is the most popular historical attraction in the Portland-Vancouver metropolitan area. It also is a major archaeological resource, with more than 2 million artifacts in its collection. Most of those pieces, gathered from more than 50 years of excavations, are kept in warehouses, along with the boxes of documents, drawings and other assorted historical records in storage that, because of severely limited physical access, obscures the fascinating and multicultural history of the place, once dubbed the “New York of the Pacific.” The fort site served as the early end of the Oregon Trail, the regional headquarters of the British Hudson’s Bay Company’s massive fur empire and the first U.S. Army post in the Northwest.

The Fort Vancouver Mobile team, with the help of dozens of volunteers from throughout the community, has produced original media, based on historical records, throughout The Village area of the site. These clips of audio, video, animation and text are intended to complement the physical environment and create visitor interactions (or events) that meld the past with the present, the physical with the digital.

Autovation

PIs: Students in the Creative Media & Digital Culture Program; Dr. Dene Grigar, Advisor.

Funding: Fellowship from Dick Hannah Dealerships, Vancouver, WA.

Awards: “Merit,” 2012 Rosey Award for “Experiential” category.

Site: http://dtc-wsuv.org/autovation/

Since the invention of the first automobile, advances in technology and human ingenuity have allowed the car to evolve into being safer and more efficient than before. In early 2012 the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry reached out to sponsor Dick Hannah Dealerships of Vancouver, WA and the Creative Media and Digital Culture program of Washington State University Vancouver to convey these advances over time using cutting edge technologies.

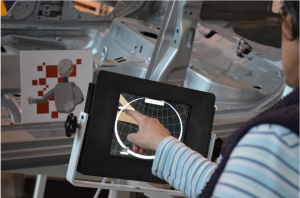

The students of the CMDC program worked on Autovation from January 2012 to June 2012. Autovation was officially unveiled to the public at OMSI on June 11th, 2012 and is currently on permanent display in Turbine Hall. The installation uses three iPads aimed at trigger images within the car frame which is angled several feet from the ground. When pointing the iPads at the trigger images in the frame, users can view drive train, safety and wheel 3D models included with animations. A description for each component is also given.

Using a Volkswagen Jetta unibody stripped to bare metal and three mounted iPads, visitors can view components of today’s vehicles through Augmented Reality. AR uses marker images, GPS, or sound to generate computer sensory effects. Autovation utilizes a series of marker images in locations where components of the vehicle would be located. The iPads track the marker images through the camera lens and the Metaio software recognizes the images and renders the desired marker. Below is a video describing in detail the use of AR in the installation.