8.0

DTC 101

Digital Art & Expression

“Digital art” refers to art that incorporates digital technologies in the making and/or in the presentation process. Even though a digital computer processes discrete data in determinate structures, a program can produce incredibly intricate and variable patterns of light and sound. Because all types of media can convert to binary code, digital art includes many remediations of old forms (cinema, sound, music, painting, photography) as well as new hybrids (VR, AR, Interactive and Computational art). The ease with which digital code can be manipulated makes digital technology condusive to creative expression. General digital creativity is therefore ubiquitous in a digitally connected world. Digital communication has become so pervasive, that some have called this the "post-digital" era.

"Digital Art" is also a contemporary art term applied to a broad range of digitally made and exhibited works that often explore themes of the digital in culture and society. Despite the challenges of selling art made of code, the art world and its market (the artists, museum curators, gallery owners and collectors) have come to accept that the most powerful and meaningful works respond to their time by using the tools and materials of their time.

The inclusive term “Digital Art and Expression” used in this chapter recognizes that it is in the unique properties of a machine (computer hardware and software) along with human creativity where innovation and novelty emerges, whether this happens in a Museum or on a Twitter account. The chapter will look at the ways in which artists explore digital code as an expressive tool and medium. All popular digital media, as we have learned from Benjamin and McLuhan, passively alter and shape individual and social behavior. Digital artists seek to challenge this passivity by using the unique properties of computers to create new sensations, perspectives, and experiences.

8.1

Computers and Art

“The Analytical Engine has no pretensions whatever to originate anything. It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform…. Its province is to assist us in making available what we are already acquainted with.” - Ada Lovelace

In 1842, Ada Lovelace, inspired by Babbage's research into his Analytical Engine, began taking notes about the creative and not purely mathematical possibilities of computation. She understood that a computer could do what one asked of it. For example, with a computer one could "...compose elaborate and scientific pieces of music of any degree of complexity or extent." Ada's intuitive understanding of code as a tool for complex semiotic processing - a tool for literary, visual and musical creation - contributed to the idea of the computer as a personal creative assistant.

Computer Art began in the 1950s as the creative play of computer engineers and scientists, because they were the only ones who had access to the computers. From these first experiments, visual artists began exploring the possibilities of computers and animation. Algorithms, as Ada had observed over a century earlier, could process any data - incuding dots, lines and shapes. John Whitney is considered to be one of the fathers of computer animation. In the early 60's, Whitney used a self-built analog computer to create animated title sequences and commercials for movies and television. A record of these visual effects he collected in a work called Catalog.

By the 1970s, Whitney began working with faster, digital computers to make work such as his psychedelic digital film Arabesque. These "primitive" works, in comparison to today's computer animation, show the remarkable ability of a computer, with human instructions, to plot change over time, to simulate organic movements and to organize elements into complex patterns. Like cinema, computers have the breath of life.

Language artists also found inspiration in computer programming. bpNichol (Barrie Phillip Nichol) was a Canadian poet, fiction writer, digital and sound poet, editor and publisher. In 1983-1884, he created a series of computer programmed kinetic poems using an Apple IIe computer and the Apple BASIC programming language. When Basic became obsolete, a student replicated the poems in Hypercard. When Hypercard became obsolete the work was rescued with a video screen capture. See FIRST SCREENING below.

8.2

Creative Coding

Artists who hand-code their art are directly working with the unique aspects of a computer's environment: random access, simulation, looping, stored data, user input, complex algorithms, duplication. Not all digital artists are coders, however. A digital photographer works with computer hardware and software and rarely needs to look at code to manipulate an image. Those artists and amateur creators who rely on common digital tools for creating images and sounds, are still creatively manipulating code. A digital "brush" that lays paint on a "canvas" is simply a precise set of instructions in the software, activated by user inputs and passed to the computer for execution. Instead of coding directly with a programming language, a majority of digital creators work with graphic user interfaces to perform specific tasks that the software then translates into code.

The following categories of creative coding do not follow any official taxonomy. These categories are just some of the often overlapping digital and computational techniques that take advantage of binary code and the computer's afordances.

Algorithmic Design

Algorithmic art refers to works that involve a process based on an algorithm, or detailed recipe, devised by the artist for the design and execution of the work. Weaving and knitting are algorithmic arts, because they are processes that involve the repetition of steps. In the 1960's, Fluxus and Conceptual artists gave up the visual object and instead wrote instructions to "execute" the work using the viewer's own physical and mental processes. While these artists meant to provoke and challenge notions of art, they were also responding to the algorithmic possibilities of machines and humans. Algorithms are deterministic. Unless there is some novel input, such as a random number or external data, an algorithm has exactly the same result each time its executes. Avant-garde composer and Fluxus artist John Cage composed many of his works with simple instructions for the musicians and often included some external variable, such as the weather or a throw of dice. His most famous work, 4'33", instructs the performer to sit quietly at the piano for 4 minutes and 33 seconds, allowing the natural sounds of the environment to be the music for a listening audience.

Algorithmic art with computers can produce fantastically complex and unpredicable patterns out of the repetition of a few simple steps written by the artist-coder, along with non-deterministic actions or external variables. Rafael Rozendaal is an algorithmic artist who works with HTML, CSS and JavaScript. He is also one of the first artists to sell websites as art objects. In 2013, Rozendaal’s www.ifnoyes.com website was sold to a collector for $3,500. This work reveals a set of geometric shapes that change size, color and position through the subtle interactions and movements of part to whole. This behavior is confirmed by the user interacting with the mouse: altering individual shapes alters all the other shapes by chains of cause and effect. The deterministc algorithm that causes lines to move, is disturbed by the variability of mouse movements.

Simulation

In general, a simulation is an imitation of a process or system. Because computers are very good at imitating processes, the term "computer simulation" has come to encompass almost any computer-based representation. A computer simulates language processing, because it can only process binary code. In fact, any reference to the external world must be "virtual" - just a description of the world as semiotic output. A personal computer has an interface that models a desktop with paper-looking documents, stacked files, folders and trash can. The process this virtual desktop "simulates" is "working a desk." Virtual simulations have become very useful in studying complex forces within natural and human systems as well as in creating the illusion of cinematic reality in games and movies. Scientists, game developers and artists create complex computer simulations by first modeling 3D environments and then simulating the interactions between elements in those environments. A computer animation of wind blowing through tree branches, would first require the 3D modeling of trees, along with individual branches and leaves. An algorithm for a directional force affecting these branches and leaves would then be written to simulate the wind. Changing variables of this algorithmic wind, such as the direction and force, changes dynamically the effects on the modeled trees.

Virtual reality (VR) reguires a set of integrated hardware and software to create immersive 3D environments, where the user's field of vision is taken up by a mathematically rendered image that changes with the users movements and interactions. These environments can simulate the physical world, or be a completely invented world with its own rules. Another type of VR technology is "augmented reality" or AR, which can integrate 3D simulations into the real world. With goggles or a headset, a user can walk around a virtual object sitting on the actual floor in front of them. VR and AR are used in many types of immersive entertainment, especially games, as well as in special types of training that need to simultate difficult or dangerous situations, such as medical or military training.

Digital artists also utilize the computer's powers of simulation. They create new worlds for aesthetic pleasure, for storytelling or for perceptual disorentation. The works below only the scratch the surface in demonstrating how digital artists have worked in 3D animation, VR and AR.

The idea of 3D animation begins with modeling objects and mapping their position in a three-dimensional space. In the above early Pixar film, a 3D animation of a real hand gives a glimpse into how today's computer animation simulates fictional characters based on the gestures and movements of real-life performers.

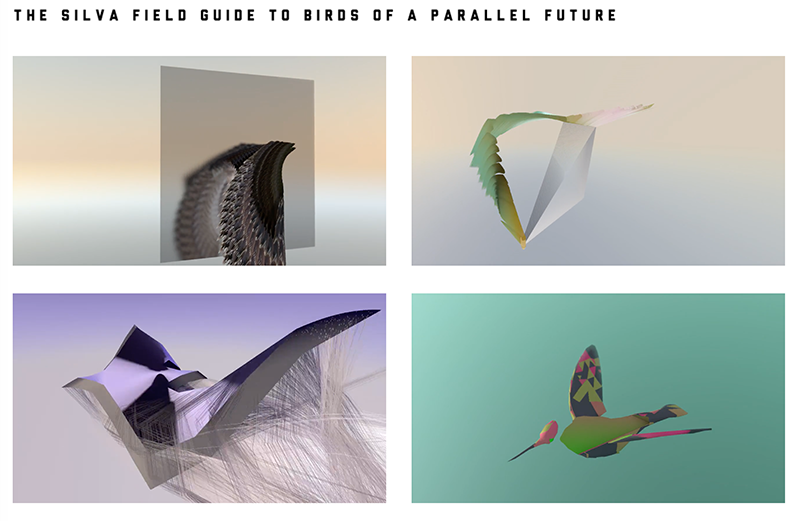

In A Silva Guide to Birds from a Parallel Future, digital artist Rick Silva creates computer simulations that investigate the mechanisms of animation in the natural world. Unlike more realistic computer simulations, that try to smooth out movements in order to appear more "analogue", Silva's work exaggerates the digital, the on and off synchronization of nested parts, in the same way that an impressionist painter exaggerates the dance of light and shadow in a landscape.

Illya Szilak's Queerskins is an example of character-driven immersive storytelling that makes use of integrated VR software and hardware: Unity Game Engine, Depthkit volumetric video, panoramic photography, 360 video and spatial audio.

The Thing Tableau by Mez Breeze is a text narrative mapped onto a 3D/VR sculpture. Suggesting the twilight state of insomnia, the work is designed for disorienting interaction by navigating around a very large robotic creature and clicking on text fragments.

Remix

Digital code makes it very easy to copy and paste. These are probably the most used tools in a personal computer. Code is also easy to manipluate and modify. Such "appropriation" or "collage" has a long history in the visual, audio and literary arts. Remix as a term emerges as music became digital in the 1980s and samples of tracks found their way into popular music, namely hip-hop. Creative appropriation and remix is now common across vernacular digital creativity and expression. YouTube alone is a vast repository of remix culture, where mash-ups of audiovisual media proliferate.

The Grey Album by Danger Mouse, is a well-known digital remix of the Beatles' White Album and Jay Z's Black Album. Because of obvious copyright violations, the album could only be aquired through p2p sharing technologies such as bittorrent. This YouTube video, a music video of a song on The Grey Album, is itself a visual remix of archival footage

Glitch and Noise

A "glitch" is a sudden surge of irregularity in behavior. Glitch art comes from the deliberate or accidental corruption of the organized digital code that make up a media file. Glitch or datamoshing, in which the code of a media file is meddled with, can be seen as generative of digital noise, when code is distorted from its intended message as an image or sound. The glitch of image files are particularly striking as the information for colors is stored in discrete units that create bursts of rainbow color when separated from the correct simulation.

Artist/writer Mark Amerika, known for his glitched, remixed and otherwise misbehaving texts, created an online work about a fictional glitch artist in the 1990s. The work is presented as a museum catalog of glitched gif animations.

Nonlinearity, Randomnness and Noise

The experience of nonlinearity in works of digital art is a result of an artist exploiting the computer's ability for random access. In computer science, the term random access, or more generally direct access, is the ability to access any element of a sequence or collection in the same amount of time. Any point is equidistant from any other point because each point - data, pixel or file - has an address and there is no noticeable space to travel to get from one point to another. The ability to randomly access any point in a system implies that there is no hierarchy in the way data is stored. Data becomes malleable, networked and open to any kind of structuring. Non-linear video editing software enables direct access to any frame in a clip, without having to fast-forward to reach it. A book, with an index or table of contents pointing to specific page numbers, is certainly designed for random access, but it is still a linear sequence that needs to be traversed. It wasn't until computers became very fast at random access, making it possible to quickly navigate nodes in a network that entirely new forms of nonlinear and multilinear expression could emerge.

Randomness and chance have always been incorporated into the creative processes of art-making. A painter allows for the random irregularities of a brush stroke. A carver works with the chance irregularities of wood grain. But what is randomness really? Material conditions determine the texture of a brush stroke and natural forces determine the grain of wood. Randomness and chance refer to events that are not humanly determined, that is something unpredicatable. How can a computer, that only takes specific instructions and that is utterly deterministic in its workings, be a machine for randomness and chance? Randomness within a closed system becomes elusive. The problem comes down to simply generating a random number. Random number generating functions in computer languages (such as Math.random()) create what is called a “pseudo-random” rather than “true-random” values. Pseudo-random values are generated by a series of operations performed to produce a sequence of numbers that repeat with a long enough period to be effectively random or sufficiently unpredicatble. Pseudo-random numbers are simulations of randomness and are in fact entirely determined and therefore predictable. Random.org offers "real" random numbers from measuring atmospheric noise. However, for most artists the pseudo-random number algorithms typically used in computer programming languages are just what is needed to create apparent variability and unpredicatle change.

Perlin noise is a technique developed by Ken Perlin that improves randomness in computer graphic renderings of natural noise in elements such as fire, smoke and water. Perlin developed the technique for the movie Tron in the early 80s and in 1997 won an Academy Award for his discovery. It works by interpolating between random values to create smoother transitions than the numbers returned only from Math.random().

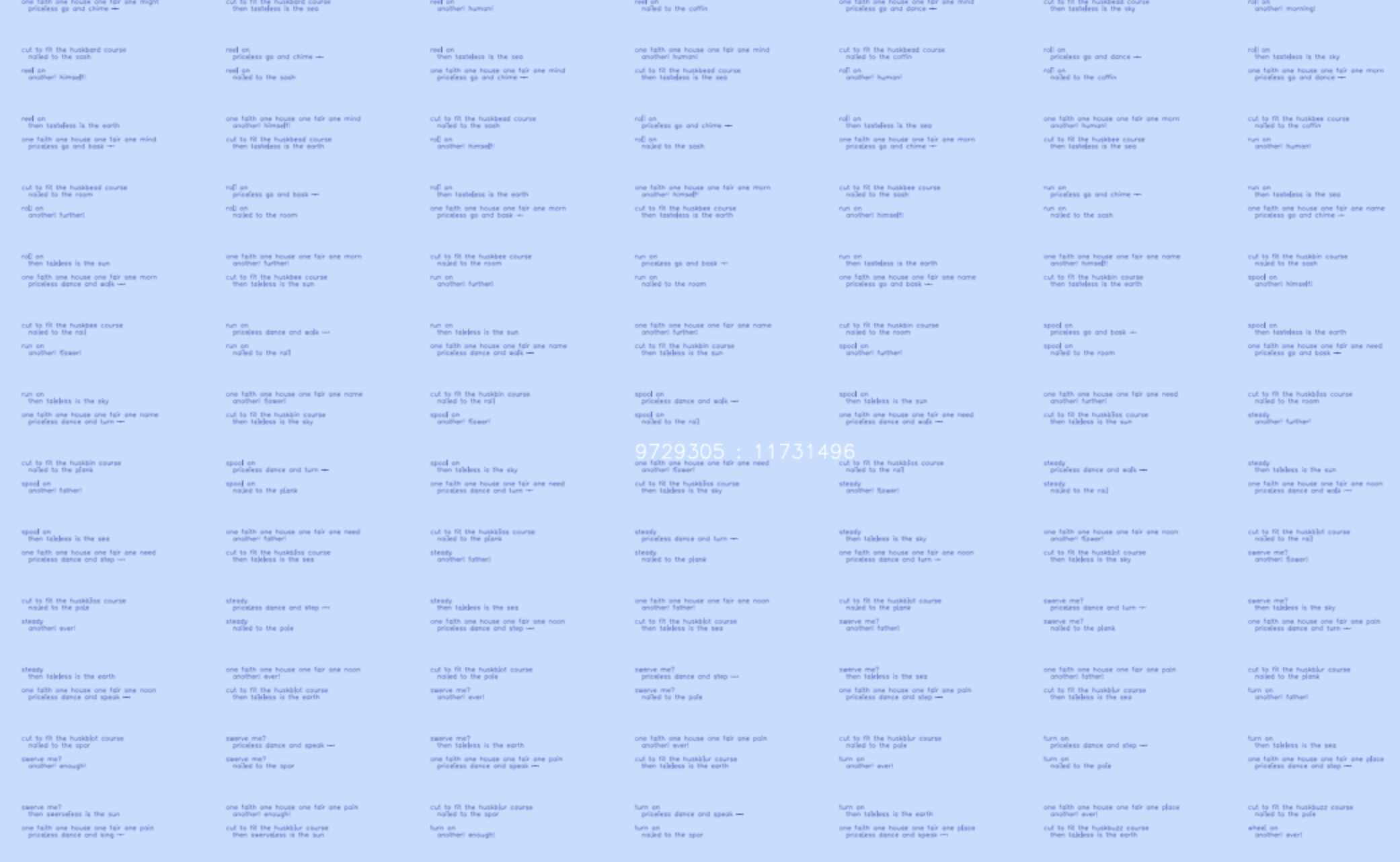

The creative possibilties of randomness and nonlinearity are best illustrated in works of digital literature. Language is granular and made for a certain amount of poetic disorderliness. Nick Montfort and Stephanie Strickland's The Sea and Spar Between is progammed to randomly select from the most popular words of both Herman Melville and Emily Dickinson and to dynamically form these words into legible if not poetic stanzas.

Net Art

Hypertext works presented on the web in the late 90s were often within the context of “net art.” Net Art was a loosely defined online community of artists, writers and coders who embraced low bandwidth connections speeds, the accessibility of HTML and JavaScript to create interactive multimedia works, the frontier freedoms of expression and copyright in the early web, and the intimacy of connecting to a readership/viewership without intermediary publishers. Net art today is any work that incorporates the internet in the process of generating the work. One of the early net artists, Olia Lialina, has tried to collect websites from the 90s as a kind of folk art where the "user" was the creator, not the consumer of high-end works of entertainment.

Jodi was an net artist collective that created linked websites made of indecipherable, but visually intricate code. A peak at the first page's source code reveals a secret image in ASCII.

Olia Lialina's net art Summer enacts or makes visible the network that the artwork is built upon. The animation of the artist on a swing is automated to display single frames of the sequence delivered from web domains around the world. In the screen grab below, observe the changing urls in the browser address bar as the animation swaps images.

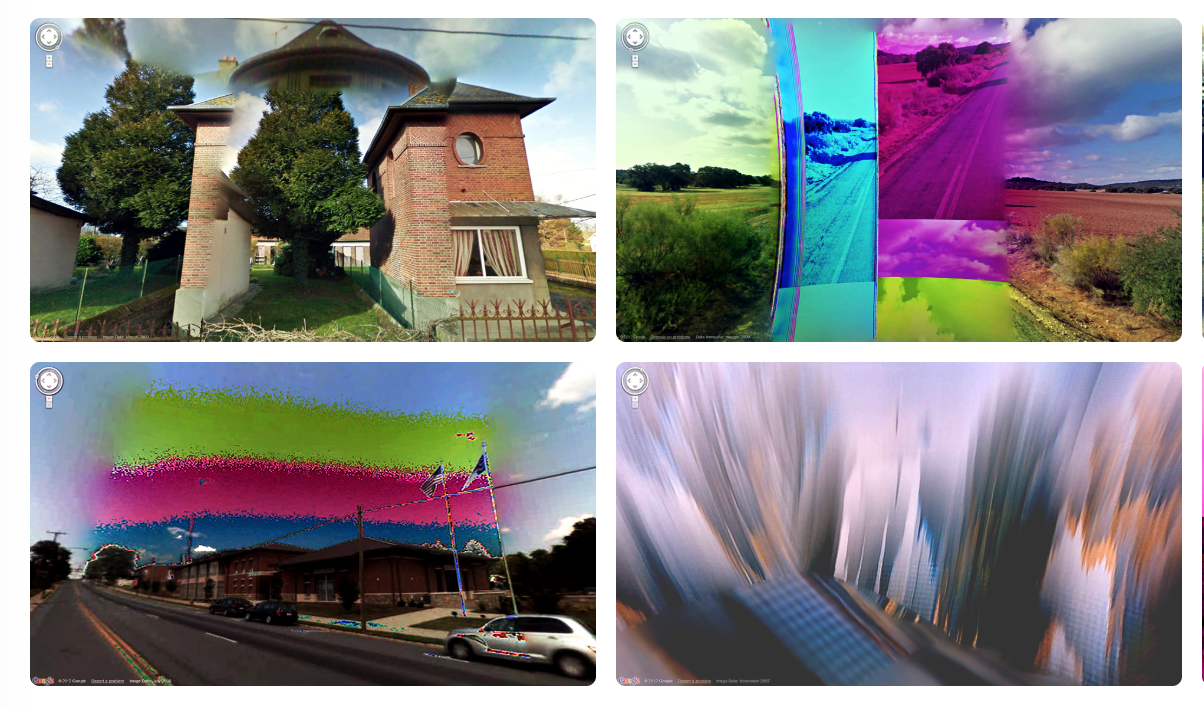

Artist Jon Rafman is an internet photographer. He "screen-captures" photos from his wanderings on Google Street View and then places these photos on a wall in a gallery. Akin to Marcel Duchamp's ready-mades, Rafman's digital ready-mades require only his selection of the found images. Are these his photos or Google's?

Another artist, Emilio Vavarella, travels on Google Street View screen-capturing all the “wrong landscapes” he encounters before others can report the error and prompt the company to adjust the images. Google’s technical glitches become the criteria for found art.

Generative & Recombinant Processes

Generative art is art that employs data, simulations, algorithms and randomness or external inputs to create an autonomous process that can undergo dynamic change. Generative artists design the process, such as a set of rules, a computer program, or other procedural invention, which is then set to run with some degree of independence. Similarly, Recombinant Art makes use of determinsitic and variable processes to select and juxtapose from a fixed set of media elements

Sound Art

Live coder, Sam Aaron created Sonic Pi, a code-based music creation and performance tool. Sam believes that a...

"...programming environment which has sufficient liveness, rapid feedback and tolerance of failure to support the live performance of music is an environment ripe for mining novel ideas that will not only benefit artistic practices themselves but also the computer industry and education more generally."

Mobile & Locative Art

Location-based or locative media refers to digital media that relates to or augments the physical location of the user. Geolocation (geocoordinates detemined by the Global Positioning System (GPS)) can customize the media content or advertising sent to a mobile device. Locative or mobile art is the creative use these spatial tracking technologies to offer multimedia experiences or stories. Such works are often based on the exploration of a specifc location, but they can also integrate the users own location in a media experience.

Artificial Intelligence

Artificial Intelligence or AI is an emerging area of digital arts that uses Deep Learning, a method for computer programs to learn complex processes by themsleves through rapid trial and error. Artists have started to "teach" AI collaborators in the creation of images, and in music composition and in filmmaking.

A collaboration between an artificial intelligence

named AICAN and its creator, Dr. Ahmed Elgammal

After Google's AI successfully beat a human Go player, filmmaker Oscar Sharp collaborted with Ross Goodwin to build a machine that could write screenplays. Their creation, called "Jetson", learned the art of Sci-Fi screenwriting by being fed hundreds of TV and movie scripts. The director shot and edited Jetson's output.

John Cayley performs conversations with Amazon's AI voice Alexa, incorprating his own software into the Alexa API (Application Programming Interface).

8.3

The Market for Digital Art

Some of the most innovative contemporary digital artists emerged as coders, once scorned then later embraced by the art elite. By 2000, there was a tentative acceptance of digital art into the art world and its markets. Why this hesitancy? Manovich’s five principles of digital media - numerical representation, modularity, variability, transcoding - do much to explain the issues of a “digital” art market. Digital tools are relatively cheap and ubiquitous, techniques are easy to learn and distribution is abundant. Digitally coded art objects can be easily copied and remixed, wiping away any distinct monetary value based on scarcity or distance. The art market has traditionally favored expertise in a specific medium, whereas digital code can simulate all kinds of mediums, not to mention countless hybrids of mediums. To confuse matters even more, some digital artists respond to the vernacular languages of online life as form and content, incorporating emojis, popular code snippets, glitch, hyperlinks into their digtal collage art, and sometimes present these works on popular social media platforms. Digital technology, as both creator of novelty and destroyer of traditional artistic values, raises important questions about art and its value and sustainability in a technological society.

Digital art is exhibited online, in public spaces, in galleries and museums and at conferences and festivals. There are also efforts to sell digital art online using Cryptpcurrencies or "Non-fungible tokens" (NFTs). Here are a few examples of an emerging online market for digital art:

8.4

Unit Exercise: Appropriate, Alter, Post

These instructions are an algorithm for digital art making.

- Find an image using Google image search and download it.

- Open the image in Illustrator, Photoshop or Gimp and alter the image into a pleasing distortion from its original state using glitch, noise, remix, color change, mask and layering

- Give the image a title and post the image to the class blog

8.5

Glossary

8.6

Bibliography

“Ada Lovelace.” Wikipedia, 29 Aug. 2019. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Ada_Lovelace&oldid=913026966.

Greene, Rachel. Internet Art. Thames & Hudson, 2004.

Hayles, N. Katherine. How We Think: Digital Media and Contemporary Technogenesis. University of Chicago Press, 2012.

“John Whitney (Animator).” Wikipedia, 29 July 2019. Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=JohnWhitney(animator)&oldid=908429741.

Lister, Martin, et al. New Media: A Critical Introduction. 2 edition, Routledge, 2009.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Reprint edition, The MIT Press, 2002.

Paul, Christiane. Digital Art. Third edition edition, Thames & Hudson, 2015.

Ryan, Marie-Laure, et al., editors. The Johns Hopkins Guide to Digital Media. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014.

Untangling the Tale of Ada Lovelace—Stephen Wolfram Blog. https://blog.stephenwolfram.com/2015/12/untangling-the-tale-of-ada-lovelace/. Accessed 17 June 2019.