Pathfinders: The Art of Early Digital Pioneers

Exhibit Opening: Tuesday, July 9; 5 p.m.

July’s Artist Talk by Stuart Moulthrop: Tuesday, July 9, 7:00 p.m.-8:00 p.m.

August’s Artist Talk by John McDaid: Thursday, August 8, 7:00 p.m.-8:00 p.m.

October’s Artist Talk by Shelley Jackson: Friday, October 18, 7:00 p.m.-8:00 p.m.

From July to October, Nouspace will host digital works created by pioneers of early electronic literature. This exciting event takes place in conjunction with the digital preservation work that begins in June at at the eLit Lab at Washington State University Vancouver sponsored by the National Endowment for the Humanities. Works by four artists will be performed and videotaped for permanent archive for the Electronic Literature Directory and other databases across the US and beyond. Selected for this project are electronic literature artists Stuart Moulthrop, Judy Malloy, John McDaid, and Shelley Jackson.

Nouspace will highlight the works of each artist. First up is Moulthrop, whose hypertext novel, Victory Garden, is considered a seminal work of electronic literature. The show opens Tuesday, July 9 at 5 p.m. Moulthrop will be in Vancouver from July 8-11 and will give an artists talk on Tuesday evening following the show’s opening.

Stuart Moulthrop

Artist Bio

Artist Bio

Stuart Moulthrop has produced many critically significant works of digital writing and art, beginning with various HyperCard experiments in the late 1980s, and the pre-Web hypertext Victory Garden (1991), which Robert Coover described on the front page of The New York Times Book Review as a “benchmark” for electronic literature. Early Web projects followed, including “Hegirascope” (1995) and “Reagan Library” (1999), both of which have been written about extensively. In the mid-90s Moulthrop co-edited the groundbreaking online journal Postmodern Culture, bringing out its first digital-only special issue. In 2000 he became a founding board member of the Electronic Literature Organization. In 2007 he released two Flash projects, “Deep Surface” and “Under Language,” which won the international Ciutat de Vinarós Prize for Digital Narrative and shared the prize for Poetry. Since 2010, Moulthrop has been working on R, a multi-part experiment in re/sourced writing based on Michael Joyce’s 2007 “novel of internet” called Was. The first phase of the project will appear toward the end of 2013. In 2011 Moulthrop was a visiting fellow at three Australian universities, and an In(ter)ventions resident at the Banff Centre for the Arts in Canada in 2013. He lives in Milwaukee, where he is Professor of English at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

About Victory Garden

About Victory Garden

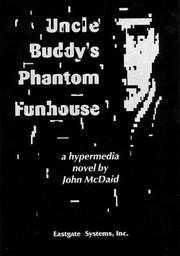

Victory Garden is a long-form hypertext fiction written in increasingly release-worthy versions of Bolter and Joyce’s Storyspace application. It was originally intended for the first-generation Apple Macintosh, with its monochrome (but multi-font!) screen whose size would these days suggest a dashboard nav system. This was long in advance of e-books and tablets, and shortly before Myst, Doom, and Netscape Navigator unleashed their graphics revolutions; in a brief, fragile, twilight of the word. The work was published in 1991 by Eastgate Systems, on the heels of Joyce’s afternoon and a little ahead of John McDaid’s Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse and Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl. Though Victory Garden has drawn some attention from novelists (Robert Coover kindly called it a “benchmark”; Sven Birkerts and Paul LaFarge mark it more darkly), I do not think of it as a novel, but rather an attempt to build a variously-traversible system of writings, some of them stories, while evading the overt mechanism of interactive fiction, a form of which I was at the time cravenly jealous. The titular garden is partly that of Borges, or Ts’ui Pên: but also a certain fantastic place called Tara in a long-gone time called the nineteen-eighties. Some of the potentially emergent stories concern love, loss, oil, madness, maps, letters, television, and a certain war on the American homefront, always in progress. Though few readers have much cared, the work can actually be read in 37 distinct ways simply by “marching through on a wave of Returns,” as the man says in afternoon — I suppose I wasn’t sure about the whole hypertext thing. Or one can hunt for specific links, which I left detectable, in a deliberate break from the Joycean model. Tucked away within the 997 text nodes and innumerable forking paths are low scenes of academic life, cop drama, strong-minded women, a Saddam Hussein impersonator, a really bonehead mischaracterization of Wolf Blitzer, heavy doses of polemic, a talkative black bird, and, as McDaid once allowed, a fairly decent car chase. For some reason there always had to be a car chase.

John McDaid

Artist Bio

Artist Bio

John G. McDaid is a science fiction writer and citizen journalist from Portsmouth, Rhode Island.

His hypermedia novel, Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse, published by Eastgate Systems, was a New Media Invision Award finalist in 1993. As a member of the TINAC collective, he has spoken on digital narrative at dozens of colleges and conferences.

He attended the Clarion workshop in 1993, and sold his first short story, the Sturgeon Award-winning “Jigoku no mokushiroku” to Asimov’s in 1995. A novelette, “Keyboard Practice,” appeared in the January, 2005 Fantasy & Science Fiction, and his most recent story, “Umbrella Men,” was the cover story in that magazine in January, 2012.

As a citizen journalist, he has written about local news and politics on his site, harddeadlines.com for the past seven years; his reporting has also appeared on RI Future.

He attended Syracuse University, did graduate work at the New School University, and is ABD in Media Ecology at NYU. He lives in Portsmouth with his wife, Karen, son, Jack, and their feline companions Curiosity and Eclipse.

Artist Bio

Artist Bio

With a literary and visual arts background that includes artists books, text-based installation art, and narrative performance art, and with experience as a computer programmer for early library systems, Judy Malloy is a poet who works at the conjunction of hypernarrative, magic realism, and information art.

Her work with nonsequential literature began in 1976, the year she started exploring nonsequential narrative in experimental artists books. In subsequent years, she created a series of card catalog artists books that were first exhibited as a series in the exhibition Judy Malloy 3X5, Visual Card Catalogs at Artworks, in Venice, California in 1979. The first artists book in her series of push-button electromechanical books was created for her installation Technical Information at SITE in San Francisco in 1981. Then, in August of 1986, she began writing and programming the hyperfiction Uncle Roger, which was first released on the BBS of Art Com Electronic Network on the WELL in December 1986.

In addition to Uncle Roger, Judy Malloy’s electronic literature includes the generative hypertext its name was Penelope; (Richmond Art Center, 1999, Eastgate, 1993) called by writer and critic Robert Coover one of the classics of the “golden age” of hyperfiction; the polyphonic narrative Wasting Time; (After the Book, Perforations 3, Summer, 1992) the early web hyperfiction L0ve0ne; (Eastgate Web Workshop, 1994) the collaborative hyperfiction Forward Anywhere; (with Cathy Marshall, Eastgate, 1996, created under the auspices of Xerox PARC) Paths of Memory and Painting (2010) composed with composite arrays of hypertext lexias; and most recently, From Ireland with Letters, an epic polychoral electronic manuscript told in the public space of the Internet.

Her work has been exhibited and published internationally including the San Francisco Art Institute; Tisch School of the Arts, NYU; Sao Paulo Biennial; the Library of Congress, National Library of Madrid; National Library of Portugal, Lisbon; Los Angeles Institute for Contemporary Art; Boston Cyberarts Festival; Walker Art Center; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, CA; University of Arizona Museum of Art; Visual Studies Workshop; the Electronic Literature Organization; Universite Paris I-Pantheon-Sorbonne; Eastgate Systems; E .P. Dutton; Tanam Press; Seal Press; MIT Press; The Iowa Review Web, and Blue Moon Review, among many others. Parts of her recent work Paths of Memory and Painting have been exhibited or presented at the Berkeley Center for New Media Roundtable, the E-Poetry Festival at the Center of Contemporary Art in Barcelona, and the University of California Irvine, as well as short listed for the Prix poesie-media 2009, Biennale Internationale des poetes en Val de Marne. In 2012, her work was given a retrospective at the Electronic Literature Organization Conference in Morgantown, West Virginia.

Her papers — including the original notebooks and programs for Uncle Roger and its name was Penelope — are archived as The Judy Malloy Papers at the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke University

Judy Malloy has also been active in documenting the electronic arts and is the host of Authoring Software, a resource for teachers and students. She has been an artist in residence and consultant in the document of the future for Xerox PARC, taught as Visiting Faculty in the Digital Media program at the San Francisco Art Institute and is a member of the Electronic Literature Organization’s Literary Advisory Board. In the fall semester of 2013, she is Anschutz Distinguished Fellow in American Studies at Princeton University, where she will be teaching a seminar on Social Media: History, Poetics, and Practice.

As an arts writer, she has worked most notably as Editor of the MIT Press book, Women, Art, and Technology, as Editor of The New York Foundation for the Arts’ NYFA Current, (originally Arts Wire Current) an Internet-based National journal on the arts and culture; and as an Associate Editor for Leonardo.

She believes that ideally print literature and electronic literature are parallel art forms where writers and artists in each medium understand each other’s vision and, as between poetry and fiction, sometimes move with ease between print and screen.

Intertwining elements of magic realism with Silicon Valley culture and semiconductor industry lore, the three files of the pioneering electronic hyperfiction, Uncle Roger, originally appeared beginning in 1986 on Art Com Electronic Network on The WELL. In the 27 years since the work began, it has been authored as a social network intervention, with UNIX shell scripts; on floppy disk with BASIC; and on the World Wide Web with HTML. In File II of Uncle Roger, “The Blue Notebook”, reflecting the increasing complexities of the narrator’s Silicon Valley life, five parallel narratives advance the story at the will of the reader. Some of the text is taken from the narrator’s notebook where, as she explains: “The things I wrote in the blue notebook didn’t happen in exactly the way I wrote them.”

“Everything I typed on the keyboard”

showed up on a large screen

which filled the entire wall at the front of the room.

Five men in tan suits were sitting around the screen,

watching the words as I typed them in.”

In the spring of 1986, I was invited by video and performance art curator Carl Loeffler, to go online and participate in the seminal Art Com Electronic Network (ACEN) on The WELL, where ACEN Datanet, an interactive online publication, would soon feature computer-mediated works of text-based art, including works by John Cage, Jim Rosenberg, and my interactive Uncle Roger.

Once in a while in a lifetime, everything comes together. In 1986, it was my experience in database programming, the idea I had been working on since 1977 of using molecular narrative units to create nonsequential narrative, the availability of personal computers that would make what I had been trying to do with “card catalog” artists books more feasible, and the arrival of Art Com Electronic Network, a place to create, publish and discuss the work.

In August 1986, for publication on ACEN, I began writing and designing the interface and programs for the hyperfictional narrative database, Uncle Roger. And in the process, I created an authoring system — Narrabase — which I have continued to develop for my work for 27 years.

A seminal interactive hyperfiction for command line computer platforms, Uncle Roger is based on a narrative and creative use of links. (originally called keywords from the database algorithms that informed this work) The composing of the three files that comprise Uncle Roger was influenced by my experimental artists books, by my experience with library database programming, by the slide-based narratives I performed at alternative art spaces in the early 80’s, and by scene-based Renaissance comedy.

The Story

“I pictured a whole line of men in tan suits

scampering around on a stage, singing

“The yield is down. I think we lost the process.”

The chorus was “We lost it in the submicron area,”

which is what Jack said next.”

ACEN’s host, The WELL was (and still is) a pioneering Northern California-based social media environment, which hosted digerati from all over the World, including Silicon Valley, where I had once lived. Thus, at the timethat Uncle Roger was created, I was immersed in 1980’s San Francisco Bay Area personal computer culture. With locations including a party in Woodside, a microelectronics lab, and an early corporate word-processing office, Uncle Roger, like the interface and the programs with which it was created, is set in this era of transitioning computer culture. Events are observed by a narrator, who in telling the story intertwines elements of magic realism with Silicon Valley culture and semiconductor industry lore.

Files 1 and 2 are interactive hypertexts in which the reader actively follows chains of links through the narrative — either one link or combinations of links using the Boolean operator “and” (“men in tan suits” and “dreams”, for instance) — and then returns to the beginning to follow another link or combination of links.

Simulating the diffuse, unsettled quality of the narrator’s changing life, the third file is generative.

The Three Files of Uncle Roger

“What I type on the keyboard appears in green

on the screen which is called the monitor.

When the screen is full, the letters

scroll up somewhere inside the machine.”

The following background information about each file of Uncle Roger is from the packaging of the original Apple II Applesoft BASIC version.

“A Party in Woodside”

During a long, mostly sleepless night after, a party is remembered fitfully, interspersed with dreams. Like a guest at a real party, you hear snatches of conversation and catch fleeting glimpses of both strangers and old friends. There are occurrences which you never observe. You meet people whom others may never meet. A fragmented, individual memory picture of the party emerges.

“The Blue Notebook”

In The Blue Notebook, the story is continued by the narrator, Jenny. The narrative is framed by a formal birthday party for Tom Broadthrow at a hotel restaurant. Jenny’s fragmented memories — a car trip with David, a visit to Jeff’s company in San Jose, an encounter with Uncle Roger in the restaurant bathroom – weave in and out of the birthday party recollections. Some of the text is taken from Jenny’s blue notebook where, as she she explains: “The things I wrote in the blue notebook didn’t happen in exactly the way I wrote them.”

“Terminals”

In January the narrator, Jenny, left the Broadthrow family and started working for a market research firm in San Francisco. As Jenny sits at her desk, memories of a Christmas party in Woodside, a trip back East for the Holidays and other things that happened come and go in her mind.

More about “The Blue Notebook”

“We walked through a door

into a vast expanse of gray cement floors.

There were no windows.

Rows of benches were covered with black and silver equipment; piles of cables;

boxes of small objects encrusted with wires;

microscopes; tv screens;

clear plastic boxes with holes in them; surgical gloves.

In the back exposed pipes

alternated with ten foot tall machines.”

In Silicon Valley, things do not happen simply and clearly. In File 2 of Uncle Roger, “The Blue Notebook”, five parallel yet intertwining narratives advance the story in sometimes conflicting ways — reflecting the increasing complexity of Jenny’s life.

The story is framed by a formal birthday party for a microelectronics company president. His party — in a Silicon Valley hotel dining room — is punctuated by the narrator’s unlikely encounter with the eccentric semiconductor market analyst Uncle Roger. And while Jenny sits at the banquet table, other narrative threads — a car trip with a former lover, a visit to a semiconductor house in San Jose — come and go in her mind.

Parts of the story are taken from her notebook where reality is difficult to separate from fiction and dream: “The things I wrote in the blue notebook didn’t happen in exactly the way I wrote them.”

Technical Information

“It’s an FX-7000G ,” said one of the men

in tan suits. He pulled a thin calculator

out of his pocket. The other two men leaned

over the calculator while he pushed some buttons.

Small grey graphs appeared

on the tiny green screen.”

Uncle Roger was first told online on the ACEN conferencing system on The WELL, beginning in 1986. Beginning in 1987, it was published online as a working hypernarrative, programmed with UNIX shell scripts on ACEN Datanet. It was also self-published as computer software, programmed with BASIC for both Apple and IBM-compatible computers and distributed by the Art Com Catalog, (a video and small press distributor) as well as exhibited internationally in the traveling exhibition Art Com Software.

Over the years, I have worked to keep Uncle Roger available to a public audience. A web version was created in 1995 and is still available at http://www.well.com/user/jmalloy/uncleroger/uncle.html

And in 2012, I recreated the BASIC version of Uncle Roger for the DOSBox emulator. Access is available at http://www.well.com/user/jmalloy/uncleroger/uncle_readme.html

Shelley Jackson

Artist Bio

From Wikipedia: Shelley Jackson (born 1963) is a writer and artist known for her cross-genre experiments, including her groundbreaking work of hyperfiction, Patchwork Girl (1995). In 2006, Jackson published her first novel, Half Life.

Born in the Philippines, Jackson grew up in Berkeley, California, where her family ran a small women’s bookstore for several years; Jackson later recalled, “I was already in love with books by then….and the family store just confirmed what I already suspected, that books were the most interesting and important things in the world. Of course I wanted to write them!”[2] She graduated from Berkeley High School,[3] and received a B.A. in art from Stanford University and an M.F.A. in creative writing from Brown University. She is self-described as a “student in the art of digression”.[4]

While at Brown, Jackson was taught by electronic literature advocates Robert Coover and George Landow. During one of Landow’s lectures in 1993, Jackson began drawing “a naked woman with dotted-line scars” in her notebook, an image she eventually expanded into her first hypertext novel, Patchwork Girl.[5] Jackson later said that she never considered publishing Patchwork Girl as a print novel, explaining,

| “ | I guess you could say I want my fiction to be more like a world full of things that you can wander around in, rather than a record or memory of those wanderings. The quilt and graveyard sections [of the hypertext], where a concrete metaphor that resonates with the themes of the work creates a literary structure, satisfy me in a very corporeal way. I salivate, my fingers itch.[5] | ” |

A nonchronological reworking of Mary Shelley‘s Frankenstein, Patchwork Girl was published by Eastgate Systems in 1995 to acclaim;[6] it became Eastgate’s best-selling CD-ROM title and is now considered a groundbreaking work of hyperfiction.[5][7] “Patchwork Girl” uses tissue and scars as well as the body and the skeleton as metaphors for the juxtaposition of lexia and link. While working in a San Francisco, California bookstore,[5] Jackson published two more hypertexts, theautobiographical My Body (1997), and The Doll Games (2001), which she wrote with her sister Pamela.

In the late nineties, Jackson alternated hypertext work with writing short stories (in publications such as The Paris Review and Conjunctions) and children’s books. Jackson has explained that she “completely ignored” one college professor who told her the key to success was focus, and added that “[s]ometimes this means shuttling manically between art and writing and other, more unmentionable obsessions. More and more, though, and partly because of the ease of mixing media in electronic work, I’ve come to see all these projects as interrelated.”[2] During this period, Jackson also did cover and interior illustrations for two short story collections by Kelly Link, Stranger Things Happen (2001) and Magic For Beginners (2005).

She published her first short story collection, The Melancholy of Anatomy, in 2002. In 2003 she launched the Skin Project,which Jackson described as a “mortal work of art”: a novella published exclusively in the form of tattoos on the skin of volunteers, one word at a time. Jackson’s first novel, Half Life, was released by HarperCollins in 2006. The story of a disenchanted conjoined twin named Nora Olney who plots to have her other twin murdered, Half Life suggests an alternate history in which the atomic bomb resulted in a genetic preponderance of conjoined twins, who eventually become a minority subculture. The novel received mixed-to-positive reviews; Newsweek called it “brilliant and funny,”[8] and The New York Times, while praising Jackson’s ambition as “truly glorious,” added that “All this razzle-dazzle, all the allusions, [and] the narrative loop-de-loops [get] a bit busy.”[6] Half Life went on to win the 2006 James Tiptree, Jr. Award for science fiction andfantasy.

In 1987, Jackson married the writer Jonathan Lethem; they divorced in 1998.[9] She currently teaches in the graduate writing program at The New School in New York City and at the European Graduate School in Saas-Fee.[10]