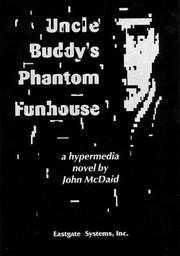

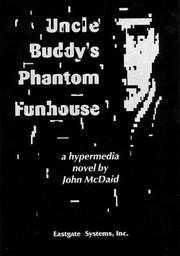

John McDaid’s Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse is, as mentioned in the previous post, out of print and impossible to find used. Therefore, scholars wanting to learn more about the work are forced to turn to secondary sources for information. Googling the title nets 32,300 hits, which seems a significant number that, at first glance, could shed light on the novel. In truth, it is really difficult to understand the breadth of McDaid’s genius through secondary sources without having access to a complete inventory of the contents of the box that constitutes the work, the art forms with which he experiments, and the media involved in the notion of Uncle Buddy as a “hypermedia novel”–and none of this information is readily found online.

John McDaid’s Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse is, as mentioned in the previous post, out of print and impossible to find used. Therefore, scholars wanting to learn more about the work are forced to turn to secondary sources for information. Googling the title nets 32,300 hits, which seems a significant number that, at first glance, could shed light on the novel. In truth, it is really difficult to understand the breadth of McDaid’s genius through secondary sources without having access to a complete inventory of the contents of the box that constitutes the work, the art forms with which he experiments, and the media involved in the notion of Uncle Buddy as a “hypermedia novel”–and none of this information is readily found online.

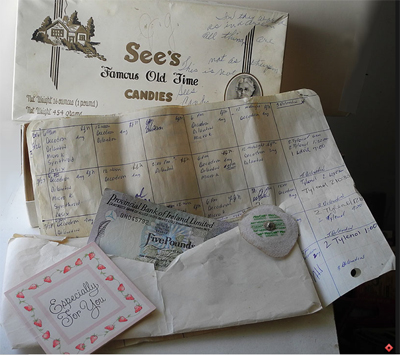

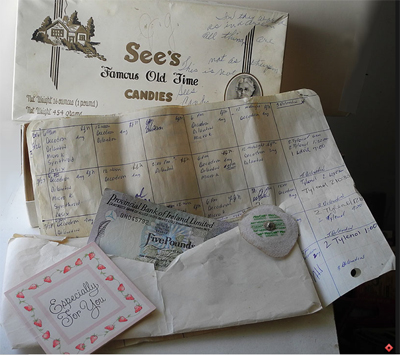

At a time when works of electronic literature were packaged in slim folios of cardboard or vinyl, Uncle Buddys’ came in a box, a black one with silver lettering. And because the boxes were purchased from a candy company, the publisher Mark Bernstein, according to McDaid, referred to Uncle Buddy’s box as “the chocolate box of death.” The conceit upon which Uncle Buddy’s was built (Re: you receive a box of seemingly random items from your Uncle Buddy’s estate) was derived  from McDaid’s personal experience: In 1986, the same year McDaid began work on Uncle Buddy’s, his dying Aunt Rita sent him a See’s candy box filled with odds and ends that constituted a portion of her “estate” she wished to give McDaid. It may be impossible to tell from this photo, but some of these contents included a 5 pound note from the Provincial Bank of Ireland, a calendar she used for remembering the medicine she took each day, and a gift card.

from McDaid’s personal experience: In 1986, the same year McDaid began work on Uncle Buddy’s, his dying Aunt Rita sent him a See’s candy box filled with odds and ends that constituted a portion of her “estate” she wished to give McDaid. It may be impossible to tell from this photo, but some of these contents included a 5 pound note from the Provincial Bank of Ireland, a calendar she used for remembering the medicine she took each day, and a gift card.

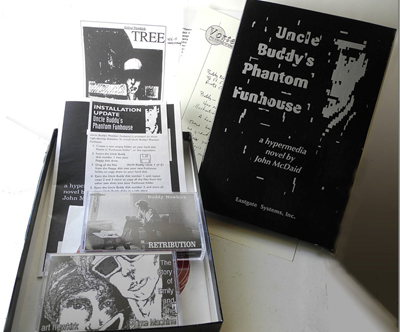

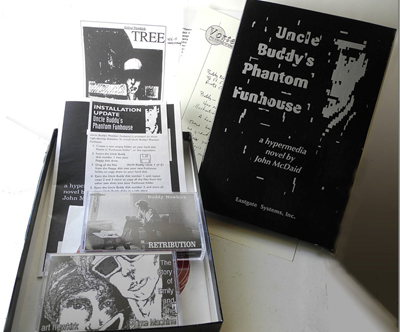

The contents of Uncle Buddy’s box includes five floppies (or the later version, one CD); a booklet introducing you to the work with directions for how to get started (in the later version, the booklet is condensed into one small sheet); two audio cassettes of music; one letter from a publisher; and one set of page proofs of a science fiction short story. While these items, like those in Aunt Rita’s box, may seem at first incongruent, they aren’t. Instead, all equally serve as elements comprising the narrative. A case in point, the borrowed copy I have includes only four working cassettes, the booklet, and the publisher’s letter. To access the work, one really needs to load the information on all five of the cassettes into a folder on the computer desktop for the work to function properly–four just won’t do. The publisher’s letter makes no sense without the page proofs because without them, the reader is not clued into Uncle Buddy’s interest in science fiction or that the genre permeates the work. Without the audio cassettes, the lyrics that make up part of the work are untethered and, more importantly, it also eliminates one of the media from the multimedia.

The contents of Uncle Buddy’s box includes five floppies (or the later version, one CD); a booklet introducing you to the work with directions for how to get started (in the later version, the booklet is condensed into one small sheet); two audio cassettes of music; one letter from a publisher; and one set of page proofs of a science fiction short story. While these items, like those in Aunt Rita’s box, may seem at first incongruent, they aren’t. Instead, all equally serve as elements comprising the narrative. A case in point, the borrowed copy I have includes only four working cassettes, the booklet, and the publisher’s letter. To access the work, one really needs to load the information on all five of the cassettes into a folder on the computer desktop for the work to function properly–four just won’t do. The publisher’s letter makes no sense without the page proofs because without them, the reader is not clued into Uncle Buddy’s interest in science fiction or that the genre permeates the work. Without the audio cassettes, the lyrics that make up part of the work are untethered and, more importantly, it also eliminates one of the media from the multimedia.

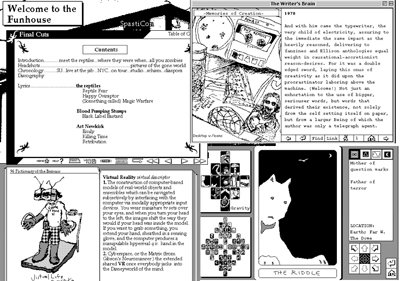

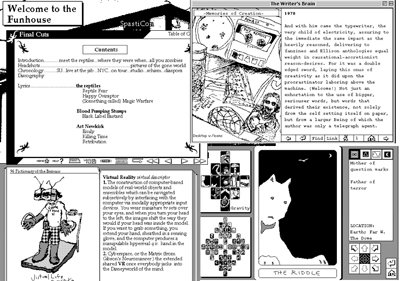

Additionally, Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse experiments with artistic forms and genres. We find generative text, photography, hypertext fiction, musical lyrics, music, sound, images, animation, the multimedia book, and text driving a story that is all at once science fiction, mystery, game, farce, and children’s book.

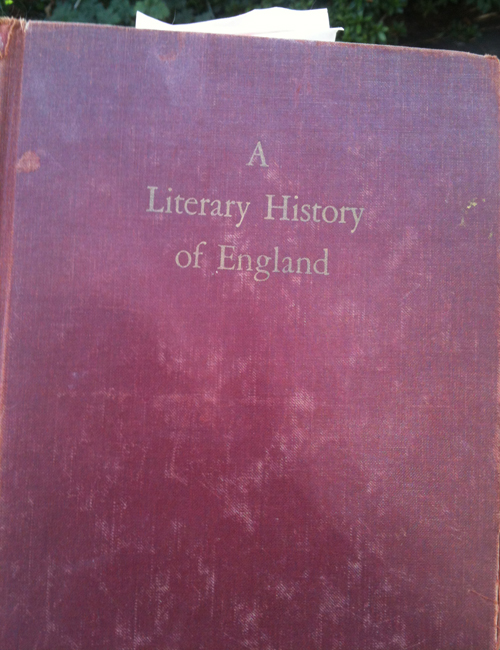

In a sense, Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse goes beyond even what Ted Nelson claims in The Literary Machine (1987) literature to be: a “system of interconnected writings.” McDaid’s literature, instead, includes a vast array of interconnected letters, email messages, tarot cards, riddles, conference program, journal (replete with essays), story story, book, screenplay, poster for a film festival, poetry, and, of course, code. Also part of this imaginative world are audio cassettes, the system audio utilized in the narrative, a map, and photos and illustrations. It is important to note that McDaid produced all of the writing and media himself, and the section of the work called Hyper Earth presages Google Earth, right down to naming the view from the street, the “street view.”

In a sense, Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse goes beyond even what Ted Nelson claims in The Literary Machine (1987) literature to be: a “system of interconnected writings.” McDaid’s literature, instead, includes a vast array of interconnected letters, email messages, tarot cards, riddles, conference program, journal (replete with essays), story story, book, screenplay, poster for a film festival, poetry, and, of course, code. Also part of this imaginative world are audio cassettes, the system audio utilized in the narrative, a map, and photos and illustrations. It is important to note that McDaid produced all of the writing and media himself, and the section of the work called Hyper Earth presages Google Earth, right down to naming the view from the street, the “street view.”

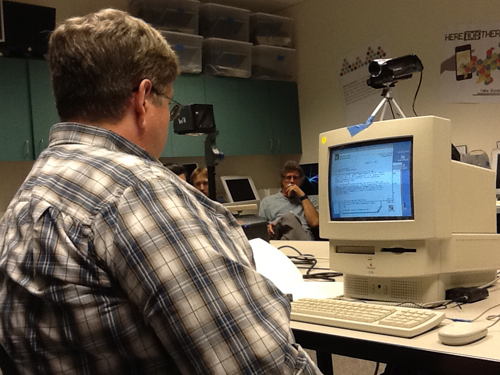

Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse is an opus and, I would add, a work of genius. It may very well be the first work of multimedia, and, along with William Gibson’s Agrippa, one of the first works of electronic literature to come packaged in a box and augmented with additional media. It may also be considered one of the first artists’ books of electronic literature. When I read this last paragraph, I am glad that Stuart Moulthrop wrote me on that August evening in 2012 from Santa Cruz where he was attending a workshop with Anne Balsamo, Tara McPherson, and other “DH folks” and invited me to join them all in a grant “to make video records of readings of early e-lit works.” It has turned out to be considerably more than that. As I mentioned in the previous post, we are contributing to the history of electronic literature, and part of that history is making others aware of the rich and complex works, like Uncle Buddy’s, that generated from the early digital literature of the late 20th century.