Though I regularly and casually use the word art to describe what I do, it comes with inward flinching. To be honest, I am much more comfortable saying hacker than artist.Are hackers not artists? We make things (poetics of code), and may even be said, after our own way, to seek beauty, or the good, or at very least the cool. But if cool, as one of my favorite teachers says, is all about information resisting information, then maybe a hacker is ultimately definable only through recursion.See artist. Then think of something else.

Art is (or commonly mistaken for) the reaching for some inescapable, indispensable, definitive statement, reflecting unique vision; something soul-forged and heroic. Mentality asserting monumentality.

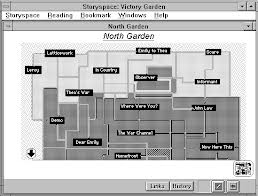

By contrast our hacker lives by smaller claims, lower forms of bricolage, finding what’s initially afforded, then wondering what the system might further yield, with sufficient encouragement or abuse. Hacking is less about monuments than exploits, and an exploit is not so much a spot on the gallery wall as unlocked door: gap, vacancy, plasma-ringed portal. An invitation: walk through, please, implying the possible, the eligible, something you should definitely try at home.

Though one’s ideals are always that – aspirations, not accomplishments – I like to think I am engaged not with CONTENT but DATA. The first word declares a withholding (con-tenir). The second reports (being a participle) that containment has failed. Something has been given – out, as publication or work achieved (how artful), but also up and away, as move in game, turn in discourse, or state of the machine. If art wants to be testimony, hack will settle for experiment, proposition, or no-doubt-pointless discovery.

Which may be for the best, if I am right about what the CONTENT-DATA shift means in the greatest sense – namely, that our species’ long investment in writing may finally be paying off in a major rewrite not just for structures of language, but also for consciousness itself – a process no one of us can hope definitively to understand, being in large measure defined as and within that process.

Maybe it’s the wrong time for Art, of a certain sort at least. Someone in our digital company recently asked, where are our masterpieces? To which the hacker responds not with mastery but piecework, saying, I don’t know, try this on. Look at the crowd, or look in the mirror – gaze at your screen, or (in this shiny age of new Glass) through it. See what yields. The masterpiece is common knowledge, a vast enterprise of clever hacks: nothing, more or less, than all of us.