Dynamic AI

Co-Creation

A Human-Centered ApproachCreated through the Digital Publishing Initiative at The Creative Media and Digital Culture program, with support of the OER Grants at Washington State University Vancouver.

Dynamic AI Co-Creation: A Human-Centered Approach is an Open Educational Resource (OER) developed with support from a Washington State University Vancouver mini-grant. It is designed as a concise guide to the rapidly evolving landscape of generative AI. The site was authored, designed, and coded with the assistance of tools such as ChatGPT, Midjourney, and Runway, drawing on teaching experience from the 2024–25 course AI in the Arts. Throughout the resource, readers will encounter short videos, project prompts, and examples that illustrate AI in practical use.

The purpose of this OER is to provide readers with the understanding and confidence to engage generative AI within creative, scholarly, and professional contexts—without being overwhelmed by technical terminology. It emphasizes foundational concepts, adaptable workflows, and human-centered practices that will remain relevant even as specific applications and platforms evolve.

Because generative AI technologies change rapidly, this resource is not intended as a step-by-step software manual. Rather, each chapter distills key strategies—how to break down a problem, construct an effective prompt, or integrate multiple outputs—so learners can apply these methods across tools and versions. Each section concludes with a Unit Exercise that encourages readers to test and reflect on these concepts through hands-on practice.

Finally, this OER takes a critical perspective on AI’s capabilities and limitations. Generative models can support intuition and accelerate iteration, but they also reproduce cultural biases and contribute to the proliferation of synthetic media. The chapters encourage both experimentation and reflection, positioning AI as a partner in the creative process rather than an unquestioned authority.

Below is a snapshot (mid-2025) of tools referenced in this text. For hands-on instructions please consult each platform’s own documentation—features change fast.

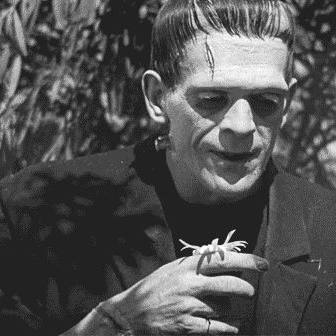

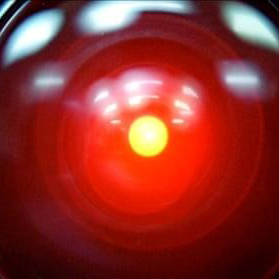

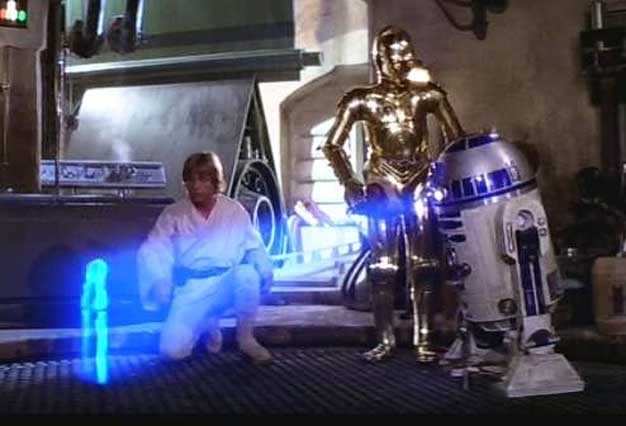

Popular stories about AI often swing between two poles: the helpful sidekick (R2-D2) and the runaway super-intelligence (HAL 9000). Both tropes let us rehearse real worries about 2025-era models that can already generate text, images, voices, and deepfakes with uncanny ease. Key challenges include value alignment (teaching machines what we actually care about), systemic bias, consent around training data, and the authenticity of synthetic media.

AI’s power to simulate human qualities—our speech patterns, artistic styles, even the look of care or emotion—creates a deeper unease. What happens when machines can mimic the very traits we think of as uniquely human: creativity, adaptability, curiosity, humor, imperfection, compassion? These are not machine qualities, yet simulation can fool us into believing we are encountering something alive, when in reality it is a reflection built from patterns in data. This is the fear of a new kind of monster: one that doesn’t simply threaten us with violence, but entangles us in illusions so convincing that we mistake simulation for substance, and in doing so risk undervaluing what is real in ourselves and each other.

When a model can imitate any voice or face, misinformation becomes cheap. Policymakers debate “authenticity watermarks,” while researchers test guardrails to stop models from revealing personal data or generating harmful content. The tension is real: we want open access for innovation and strong norms to protect people from harm.

R2-D2 offers a useful model. It doesn’t talk like a human or pretend to understand our emotions. It doesn’t need a face or a “soul.” But it gets things done, and people trust it. Maybe our machines don’t need to become more human—they just need to become more reliable, more useful, more aligned. We don’t expect our pens or notebooks to feel, just to work. Generative AI can serve in similar ways, augmenting without impersonating.

Spike Jonze’s film Her remains a useful metaphor: the AI assistant Samantha feels caring and intimate, yet her superhuman scale ultimately disconnects the protagonist from organic relationships. This highlights the danger of AI as a substitute for what only humans can give each other: empathy rooted in lived experience, care bound up with vulnerability, and connection forged in imperfection. The ideal, then, is not for AI to replace these things but to scale with human needs—to be a partner in expression, in work, in exploration—while leaving the core of human life intact. As we fold AI into daily life—study buddies, writing partners, emotional support bots—we need cultural practices (bottom-up) as much as regulation (top-down) to keep the tools in healthy proportion.

In short, the central concern is not whether AI is “good” or “bad” but whether we can learn to live with powerful simulations without being deceived by them. The challenge is to design and use AI in ways that help us live more fully human—messy, creative, emotional, adaptable—rather than narrowing those qualities or outsourcing them to machines.

This early techno-thriller imagines a U.S. defence AI that links up with its Soviet counterpart and locks both superpowers out of the nuclear arsenal. Half a century later, the lesson still stands: never outsource final authority to a black-box system you can’t unplug.

Ada Lovelace once imagined an “engine” that could weave algebra and art together. Generative AI finally realizes that dream at scale: writers bounce ideas off language models; historians explore synthetic reconstructions; musicians co-compose with text-to-music systems. For humanities classrooms, AI is both a subject and a medium—something to study critically and to create with playfully.

When students train a model on local archives or personal diaries, they practice close reading, curation, and critical coding. Such projects keep human questions (context, meaning, ethics) at the center while using machine speed for exploration.

Personal tutors used to be a luxury. Now free chatbots can break down calculus problems or rehearse a Spanish conversation on demand. But the same tools can short-circuit learning when they hand students finished answers. Educators face a design challenge: how to use AI as scaffolding (hints, analogies, feedback) rather than a one-click shortcut.

Practical moves include “zero-shot” oral exams, transparent citation policies, and assignments that ask students to critique or improve a model’s output. When AI is framed as draft rather than finished, it becomes a catalyst for deeper thinking.

Time to set the gears turning. In this exercise you will draft a creative-research project with ChatGPT (free or Plus). The aim is to test how AI can accelerate early ideation while exposing its blind spots.

Introduction: I’m a 25-year-old writer obsessed with short stories and graphic novels. I’d like a GPT that riffs on my prose style, brainstorms visual panels, and keeps me on schedule by chunking big tasks into sprints.

Objective: Build a creative partner that studies my sample texts, suggests story arcs, drafts panel descriptions for Midjourney, and reminds me to ship work every Friday.

Introduction: I’m a biology major who teaches forest camp to kids. A GPT that mixes ecology facts with art prompts could help me design activities that blend observation, drawing, and music in the woods.

Objective: Generate lesson plans, safety checklists, and creative exercises (e.g., “compose a birdsong chorus”) that adapt to different age groups and local flora.