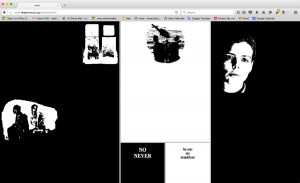

Recently, I have had the pleasure of exploring a work titled “My boyfriend Came Back From the war” by Olia Lialina. In doing so, I saw many themes that harkened back to previous hypertext works. Multilinearity was the most evident of these, as the reader is presented with multiple paths to choose from in the form of hyperlinks. Another theme I noticed was the use of fragmented text; the idea of presenting a story in only small passages at a time is not commonly found outside of hypertext works. Third, the reflexivity— the author’s awareness of the medium—was very evident. Lialina saw the affordances provided by HTML and capitalized on it, presenting multiple blocks of text at once to the reader and utilizing customizable line bars. Like some hypertexts, it was also a multimedia work, and contained images that helped to enhance its meaning to the reader (the darker tones and blurry images enforce the idea that the union of the lover and the boyfriend was not a happy one.)

Despite the references to earlier hypertext works, Lialina’s piece also differed from them in key ways. The first thing that caught my attention was the ability for the reader to slide various bars across the screen to enlarge or shrink the text within a given cell. This strongly contrasts with my past experiences with hypertexts work, where the reader is usually presented with a single, unmoving cell at a time. This work allows the reader to not only customize their experience, but to also experiment with a work on another level not offered in earlier hypertexts like “Uncle buddy’s Phantom Funhouse” or “Afternoon: A Story”. It invited me to not only view the work, but to also participate in its creation by reorganizing the cells. I found this to be quite engaging as a reader, as I could position the texts in ways that changed my understanding of the story being told. By allowing the reader to engage with the work in this way,

“Lialina aptly uses the web to interrogate our understandings of the production and organization of memory.” (Rhizome.org)

Another aspect I noticed about this piece that differed from earlier hypertext works was its small size. Most of the published hypertexts that I have seen are larger and more complex. I have a feeling that if Lialina had run this work by a publishing company, they may have been slightly underwhelmed. Though her work does deserve attention, it made sense to me that she would choose to post “My Boyfriend Came Back from the War” online rather than attempting to impress various publishers.

To conclude, I found Lialina’s work to be a refreshing break from the conventionalities of hypertext while also following traditions that had been previously set in place. Though the piece is small, it introduces new ways for readers to experience hypertext that makes her a true pioneer in the field.