Kathi’s Curatorial Statement

E-Literature At the Library of Congress

The Catalog and the Ephemeral

The twenty-seven works featured in the “Electronic Literature and Its Emergent Forms” exhibit, part of the Library of Congress’ first Electronic Literature Showcase, span thirty years of “digital born” electronic literature: stories designed to be read on a computing device and which “work with an important literary aspect that takes advantage of the capabilities and contexts provided by the stand-alone or networked computer” (Hayles). Or, as my students said, stories that change when you mess with them.

Dene Grigar and I designed “Electronic Literature and Its Emerging Forms” to enable a physical experience of e-literature in which guests to the exhibit and online might engage the works, literary influences and artistic practices of this “emerging” field. It’s emergent because smart phones have habituated readers, particularly teens and kids, to interactivity as foundational to reading. They also expect stories they encounter on devices — as opposed to the books they read in school — to be multimodal. The site Dene built links readers directly to the works, many of which are available for free in the browser. Though we are thrilled to offer online access to most of the works, we believe the exhibit delivers an experience that the digital alone cannot convey, the serendipity of conversation among guests chief among these things.

The twenty-seven featured works, all by American authors, are the main attraction; they are organized into five generically-specific stations which also roughly correspond to historical era, Station #1 being the earliest and Station #5 being the most recent, though new works are sprinkled through all stations except #2 featuring hypertext. The Electronic Literature Stations are displayed down the center of Whittall Pavillion. We’ve designed the physical space to promote flow between literary and cultural “Contexts” and “Creation Stations,” where guests can “get their hands dirty” making art using techniques from e-lit’s present and past. We think of “Contexts” and “Creation Stations” as complementary portals into the literary works. We believe that working with tools, “making stuff,” gives guests a more intimate vantage on the work.

At the Creation Stations, guests can arrange and break “cut-up” poetry, type concrete poems on a manual typewriter, and engage constraint-based writing games invented by the Oulipo, some of which electronic literature artist Scott Rettberg has adapted for machine writing. Read about his method of composition here. See also Leonardo Flores’ 5-part series about Frequency in his daily scholarly blog, I ♥ E-Poetry, which features more than 450 short posts about works of electronic literature.

Guests wishing to experiment with the branching structures of hypertextual fiction will stitch or staple “lexia” (bits of story) onto a vinyl shower curtain, a technique invented by Deena Larsen in the early 1990s as glitch-free way to present Marble Springs while she traveled on the road. Creation Stations #3 and #4 invite simultaneous virtual and exhibit guest participation. Exhibit guests can stack up spine poems at Creation Station #3, then visit Electronic Literature Station #3 to engage Jody Zellen’s mobile app “Spine Sonnet.” Virtual guests can use their own books for spine poems. All guests can load their creations to Spine Poetry, a website my students and fellow faculty member Jesse Stommel created to forge a connection between books, electronic literature and participatory culture. We believe this exhibit’s openness to virtual engagement makes it a wonderful instantiation of the Library’s mission “to further the progress of knowledge and creativity for the benefit of the American people.” Creation Station #4, a set of exercises in time-based, collaborative writing, collapses the distance between virtual and embodied writers. It’s an experiment to test the unique affordances of embodiment at an exhibit: does physical, ephemeral community yield traces in the collaborative writing? If virtual guests use “insert comment” on the G-doc, will it achieve the same effect?

At our Contexts stations guests will find literary and cultural antecedents and responses to electronic literature that broaden the scope of each Electronic Literature Station. Additional contexts convey a history of mobile storytelling dating from the American Revolution to the present day, and a post-print aesthetic disclosed in a few recent books by Mark Danielewski and Steven Hall. Pattern poetry, concrete and cut-up poetry, constraint-based writing, Lawrence Sterne’s graphical experiments in Tristram Shandy (1760); books by international and American experimental writers (Nabokov, Borges, Calvino, Cortázar) whose methods are hospitable to hypertext; the original Pong playable on an Atari console, and Choose-Your-Own adventure stories; a selection of “Great American Novels”; and artists’ books, collections of images and writing about conceptual art, pop-up books, comic books and graphic novels, and documentation of handmade books with computational affordances built into the artifact.

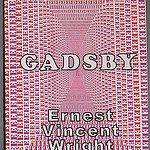

Constraints teach us something, as anyone who’s ever tried to write a sonnet can attest. Henry James was piqued by the lack of discernable constraints in novels by some of his contemporaries. He derided the “accidental and the arbitrary,” the “loose, baggy monsters” that result when an art lacks compositional integrity. But electronic literature foregrounds the “accidental and the arbitrary” in lieu of genius. What would The Great Gatsby be if Fitzgerald had been constrained from using the letter “e”? Gadsby (1939) Ernest Vincent Wright’s lipogrammatic novel of 50,100 words, omits the letter “e,” the most common letter in English.

This rare, American, self-published novel is on display in our Contexts station supporting “From the Great American Novel to Digital Multimodal Narrative.” Nick Carraway’s retrospective on Gatsby would be impossible if the novel couldn’t use the word “he” or the verbal past tense “-ed.” In Gadsby, Wright’s lipogram clears a path Georges Perec would blaze in his lipogrammatic novel La disparition (1969) (which also omits the letter “e”) and his masterwork La Vie mode d’emploi (Life A User’s Manual (1978).

Henry James knew that paper would always absorb ink. E-lit artists often don’t know from the outset how the software in which they’re authoring will respond both to their commands and the whims of their fancy. In fact, some artists create stories just to test what the software can do, and then evolve a story based on the dynamic interplay between imagination and the authoring software’s refusals and permissions.

The idea of an “interface” is a relatively new one for most of the reading public because a print book almost always works. Spines get broken, pages get torn: real violence needs to be done to a print book before it stops working. But e-literature can break without any violence at all; it breaks just sitting around while new devices, operating systems and software are introduced. E-literature’s dependence on machines that become obsolete makes e-lit fragile. We think of the digital as being permanent. But books hundreds of years old are just as operable today as they were the day they were printed, while drawers full of diskettes and floppies from the 1980s and early 90s cannot be read on devices produced today. That’s why the Library’s leadership in establishing digital preservation practices is crucial to documentation of our recent digital past; not all e-lit authors can preserve files in formats that aren’t software-dependent. This Showcase might bring together interested parties in fruitful conversation.

Shakespeare’s contemporary and fellow playwright Ben Jonson said of Shakespeare: “He is not of an age, but for all time.” E-lit, by contrast, is of an age. This exhibit highlights the mercurial terms of collaboration between artist, machine, software, and reader. Katherine Hayles, among the most distinguished e-lit scholars, wrote compellingly in a recent book (and related article) about the role of the “non-human” in shaping human attention. Attention “is engaged in a feedback loop with the technological environment” to such an extent that “[t]echnical beings and living beings are involved in continuous reciprocal causation” (see her argument in “Tech-toc”). That phrase by Hayles, “continuous reciprocal causation,” could also describe the e-lit composition process itself.

All of the works in “Electronic Literature and Its Emerging Forms” demonstrate the recombinant possibilities of human and machine co-adaptation. The most directly observable example of such co-adaptation is Michael Mateas and Andrew Stern’s Façade (2005), on display at Station 4 “The Great American Novel to Digital Multimodal Novel.” Façade is “expressive AI,” an interactive drama that harnesses the expressive power of artificial intelligence to allow a reader’s typed responses to drive the work’s procedural animation.

Like Façade‘s thematic sibling Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1962), Façade has a clear narrative trajectory. But unlike the theater-goer, who knows she can’t influence the actors’ choices, the AI gamer/reader types conversational sentences to intervene in the 3D-couple’s acerbic bickering. The game becomes a challenge to discover what sort of comment might stop Trip and Grace from becoming Albee’s George and Martha.

If this Exhibit historicizes the computer as a cherished if unreliable partner to e-lit artists, it also sheds light on what kind of e-literature endures. Jill Walker Rettberg, in her deft article “Electronic Literature Seen From a Distance: The Beginnings of a Field” argues that the ISBN played a crucial role in making early hypertext electronic literature visible to libraries and booksellers. Works of e-literature authored for display in browsers (that is, most works authored after 1993) lack ISBN numbers because there is no physical, material object to sit on a shelf or be shipped to a buyer. Consequently it is almost impossible to find browser-based e-lit in library catalogs.

Grant-supported databases of electronic literature like ELMCIP [Electronic Literature as a Model of Innovation and Creativity] and the ELD [Electronic Literature Directory] exist as a kind of patch to this problem. Were those databases to vanish — as they rely on soft money, disappearance is possible — a curious e-lit reader would have personally to assemble an overview of the field. Amanda Star Goulding’s excellent “Bibliographic Overview of Electronic Literature” is aimed at a scholarly audience; but no overview can replicate the scope of a cataloging system that would relate attributes of electronic literature to those of the literatures that come before and after it.

That’s why this Electronic Literature Showcase hosted by the largest library in the world is so important. It introduces to Americans and citizens everywhere the art that mirrors back to us the fragility and ephemerality of our toehold in the past. What should we preserve? How might we preserve it? Is there a unique value to “use,” being able to view work on original machines, systems and software? The recent spate of high-profile museum exhibits about video games — the traveling Game On and Game On 2.0, the Smithsonian’s The Art of Video Games and MoMA’s Applied Design — suggest our wish to preserve hands-on access to the narratively expressive dimensions of human/computer interaction. The tremendous interest in those shows suggests that for most people it’s not enough to read about such things. They want to play and touch them.

Just as conceptual artists defamiliarzied gallery space and the notion of what counts as “art,” so too electronic literature jostles our received notions about computing and reading. Pattern poems from 500 years ago look mid-twentieth century; early works of hypertext engaged on a Mac Classic activate a sense-memory rooted, it seems, in a different lifetime.

“Reading is a solitary undertaking, but when it takes place in front of others it becomes an act of communion,” notes Simon Gikandi in his recent PMLA Editor’s Column “The Fantasy of the Library” (PMLA 128.1, 2013). E-literature reframes key elements of the library experience without dislodging the communion we embody together. Whether in the Main Reading Room at the Library of Congress, or at the wooden tables at your local library; in the audio stories pinned to maps and accessed via your phone, or the poems you scroll through as your train glides to work: these are our new literary communions, and they happen now where ever humans happen to be. In “Electronic Literature and Its Emerging Forms,” we tell one story of the Library as a physical space, a home of our heritage and protean futures.

Image Credits and Permissions:

Spine Poetry image by the author. Deena Larsen Shower Curtain at MITH: Creative Commons Non-Commercial Share-Alike license. Gadsby image by Flickr user cdrummbks sharable by Creative Commons license. Façade image courtesy of the authors. Social reading at MLA13 image by author.