A big fan of the ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ text-based game format, I was very excited for this week’s assignment. The games I chose to explore were Galatea, and Ad Verbum. While Galatea drew my attention more, Ad Verbum made me nostalgic for the ‘Escape Room’ games I used to play.

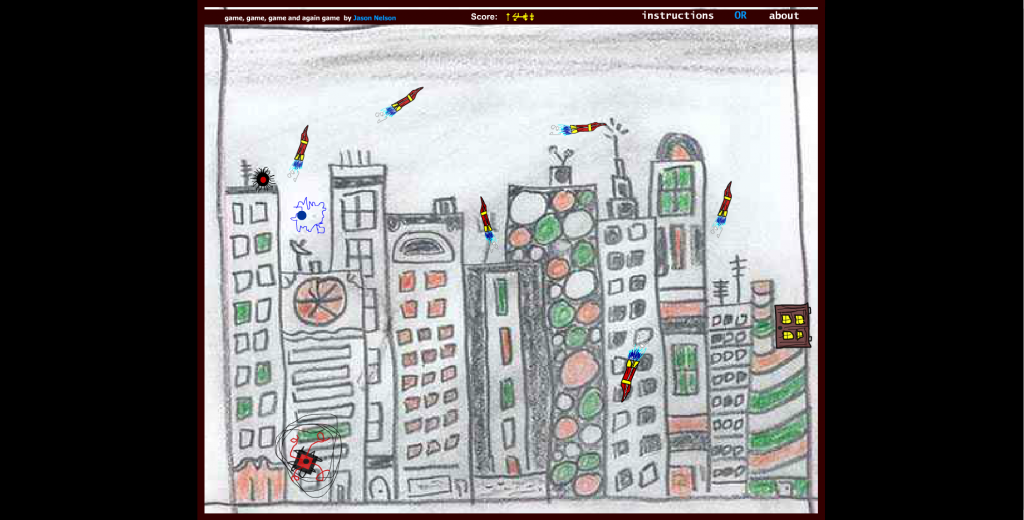

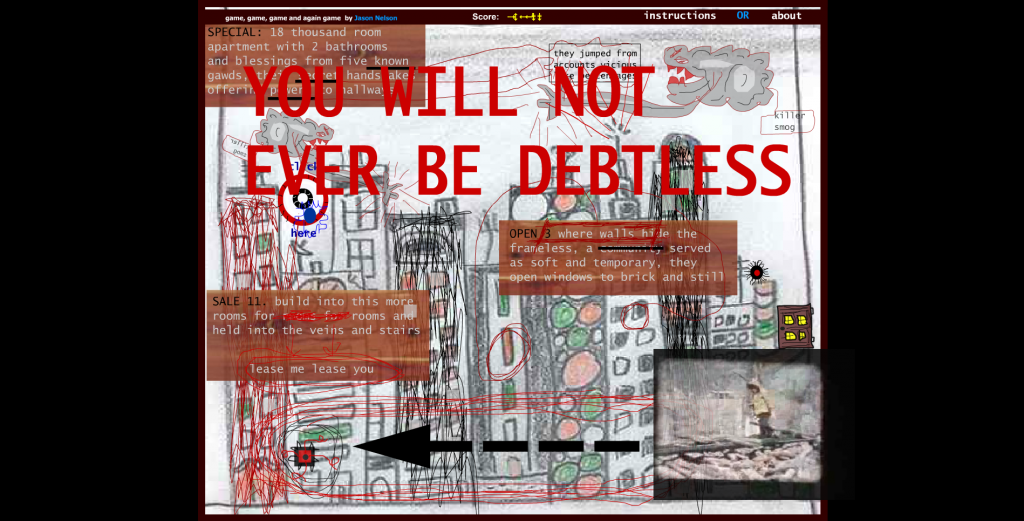

Ad Verbum gave me more of an ‘open-world’ sense than Galatea did, seeing as Galatea is set in one room only. I did not explore ALL of Ad Verbum; I got up to the fourth floor and mostly stuck to the first and second floors to see what I could find. I kind of put me off that there were some rooms that, if I could not find a way out (I never did), I was sent back to the foyer to start over.

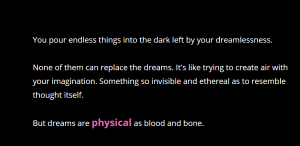

As I mentioned, Galatea definitely had more of my interest, primarily because the point was to interact with another character. My first and second play-throughs were quite short before I realized that I should not ‘walk away’ as it ends the game. The first time around, the conversation was light and informational. But as I kept on playing, the course of the game grew darker and darker; her artist committed suicide, she has a sense of dependency on him, so what is the point of her existence?

Ad Verbum gave me a goal once I tried the front door (which was the first thing I did) and realized that I had to find a way to complete the game in order to escape. Galatea, I was not so sure about, apart from just getting as much information as I could. It absolutely challenged my imagination, as my own writing is more character-driven than by setting. I would definitely go back to this game.

Over the years, hypertext has been non stop evolving. With

Over the years, hypertext has been non stop evolving. With