Although 1969 provided no technical advantage for Robert Coover to create a piece of hyptertext fiction, he instead wrote what would essentially be the inspiration for hypertext fiction by forcing the reader to use as little information as possible to string together a coherent story.

In his piece “The Babysitter” a mundane plot of a babysitter washing the kids and putting them to sleep takes multiple perspectives in a non-chronological order. However, the lack of chronology is not what is confusing and captivating to the reader. What catches the reader’s attention is the fact that each perspective of the story includes that person’s imagined story of how the rest of the night unfolds. The babysitter’s boyfriend and his friend imagine raping her or seducing her, the babysitter imagines accidentally killing the baby, the father of the children imagines cheating on his wife, etc. These are just some examples of the various plot lines in the story, and some of the characters even create multiple stories within their minds about what actually happens. As a result of this mixing pot of plot lines, the story seems to constantly be correcting or contradicting itself, further adding to the confusion and noise that the short story creates.

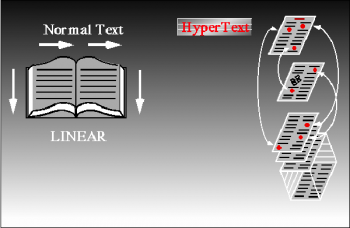

This piece was very important for hypertext fiction, which is, at its very basic structure, a mixture of technology with writing to add to the story in a way that an analog piece of writing could not do. A common feature of hypertext fiction is interactivity, meaning that the story can branch off into multiple paths, or further immerse the reader by putting them into the story, and a countless amount of other techniques. In his novel Electronic Literature, Scott Rettberg states that “hypertext fiction may not have swayed the culture to accepting nonlinear storytelling on the computer and the network as a successor to printed books, but it has served as a foundation for many new types of literary work in digital media” (Rettberg, 86). An overall criminally overlooked genre of writing, hypertext fiction has nonetheless proved influential for postmordern writing. Nevertheless, hypertext fiction’s influence will likely continue to appear in new writing, both digital and analog, but it all starts with “The Babysitter”.

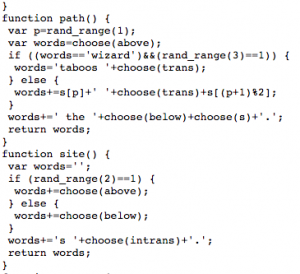

“Taroko Gorge” by Nick Monfort is an example of a poem generated by a computer, or combinatory poetics, as outlined in the Electronic Literature Organization’s list of existing electronic literature practices as part of their definition of E-lit. It fulfills John Cayley’s short definition of E-lit as it is “writing in networked and programmable media” and is primarily an example of writing in a programmable media. It also a good example of Stephanie Strickland’s definition of E-lit, which she says

“Taroko Gorge” by Nick Monfort is an example of a poem generated by a computer, or combinatory poetics, as outlined in the Electronic Literature Organization’s list of existing electronic literature practices as part of their definition of E-lit. It fulfills John Cayley’s short definition of E-lit as it is “writing in networked and programmable media” and is primarily an example of writing in a programmable media. It also a good example of Stephanie Strickland’s definition of E-lit, which she says