I took some inspiration from kinetic poetry like Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries in the teaser video for The Monolyth project.

To conclude the semester in my electronic iterature course, I decided to attempt to create my own piece of E-lit. My project began when I read Mark Amerika’s Grammatron as part of a class assignment and immediately began designing my project, first as a personal project and later as my class project.

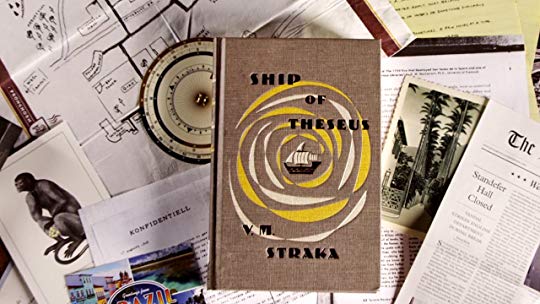

The writing and non-linear structure of the story struck me as something completely unique from what I’ve experienced before. While other non-linear narratives, especially the classic “Choose Your Own Adventure” books that I read in my youth typically depicted a branching narrative in which choices and exploration of a fictional space led to multiple outcomes, Grammatron navigated through conceptual spaces, linking pieces of prose together like a wiki site and left the user to piece together the narrative from the fragments. The fractured narrative and the juxtaposition of occultism and technology reminded me of a malfunctioning mind. As someone who has dealt with mental illness most of their life, I was inspired to tell a similar narrative by focusing on the theme of mental illness through the analogy of broken machinery. This project became as much a personal experiment in the methods of multimedia and electronic literature, as it was a way to finally express a side of myself that I couldn’t through old media alone.

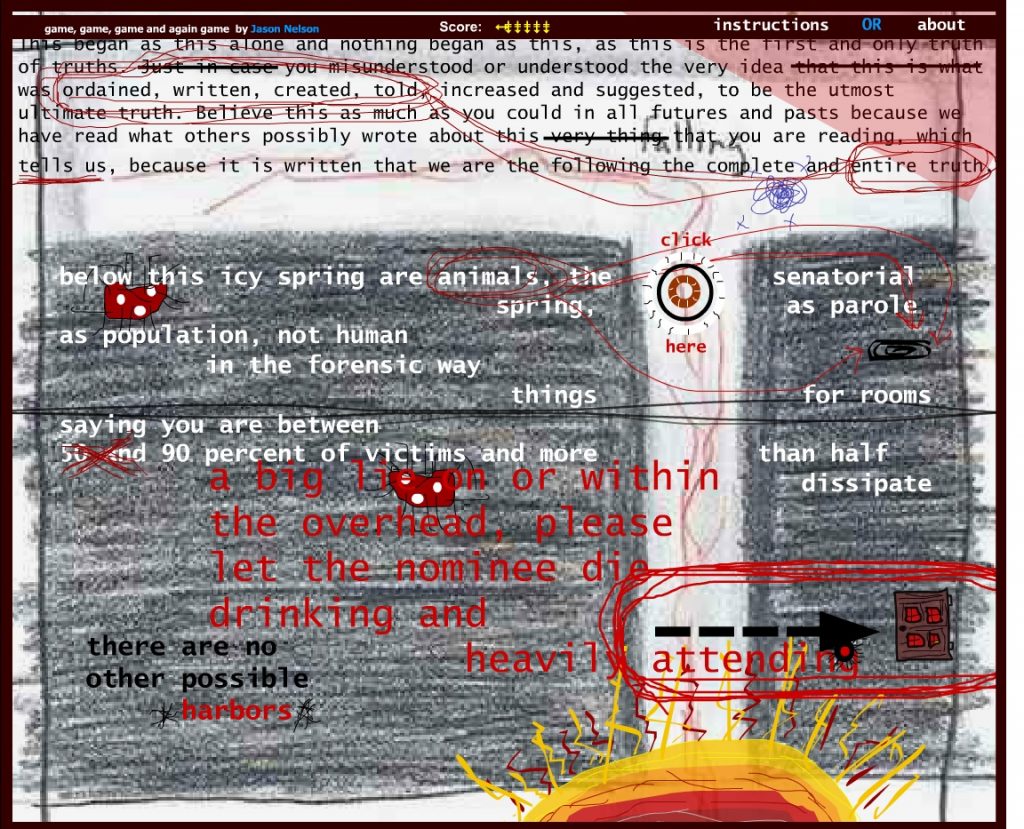

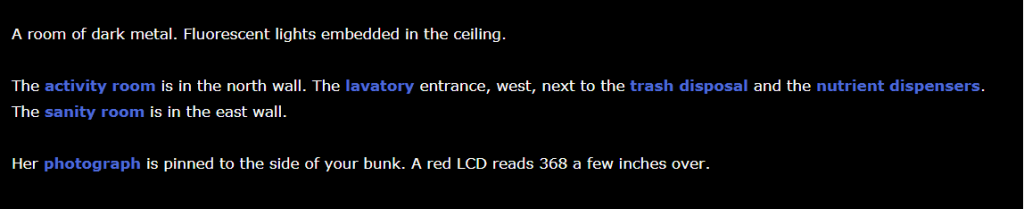

Over the course of the project, I experimented with Twine to create a rhizomatic structure to the lexia/passages of the project that would allow the user to follow intuited tangents in the narration to explore the conceptual space of the story. Multi-media, hypermediacy, and remediation were all aspects I wanted to incorporate. I used glitch aesthetics and data bending to create the visuals of the project, both of which are derived from network writing. I took several of the images and imported them as raw data into programs such as Audacity, which allowed me to indirectly manipulate the data of the images for surprising effects. The audio-loop that drones in the background was the result of original music filtered through layers of analogue and digital translation: a distorted electric guitar played through an amplifier, picked up by a cellphone microphone, compressed, sent over the internet, decompressed, and finally digitally altered through a sound editor.

Furthermore, throughout the narrative, I explored network writing by trying to structuring the branching passages/lexia to draw parallels between the tangents of intrusive thoughts and the interconnectedness of the World Wide Web: as the protagonist’s mind begins to dissolve into the Monolyth computer, his thoughts connect to files and documents within the network in the same way as his uncontrollable thoughts.

Combinatory elements take place behind the scenes of the project as new passages/lexia are opened at random by Twine’s “either” macro, representing both the unpredictable and uncontrollable nature of intrusive thoughts but also the anomalies and glitches that arise from complicated machinery in a network.

With digital technology, we’ve had to reconsider what art and literature can entail. We create art and literature and we create technology, but our creations also change us and how we experience the world. With new technology comes new potential for creation, not replacing but along side the old media, and we’re only beginning to scratch the potential granted us by digital technology. My goal with this project was to pay homage to the bright and growing field of electronic literature and the way it can speak to each of us.

The current version of Monolyth is hosted at the following address:

https://twineproject.neocities.org/