Artist Statement

Mallory Hobson

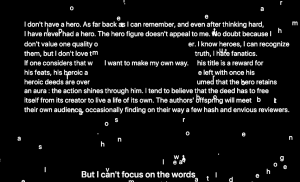

For my E-Literature Final Project, I created a kinetic poem in video format. Inspired by both kinetic poetry and cinema writing, I took a poem written for my Creative Writing: Poetry class and adapted it into a fully digital piece of literature. My intention was to evoke the feeling of running from a stressful situation, juxtaposing clear, calm reality with hazy, anxious memory through both text in motion and video cuts.

My first source of inspiration was MUDs and SOFTIEs by David Jhave Johnson. Johnson’s works were the first time I had seen poetry in a video form that wasn’t simply a recording of slam poetry (or written poetry being read aloud) but a truly multisensory experience; I was struck by how intriguing, even intimate, his poetry was, and I wanted to attempt to replicate the emotions he inspired within me.

Other inspirations were Stephanie Strickland, with her piece The Ballad of Sand and Harry Soot, and Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’ Rain on the Sea. Strickland’s piece was delicately evocative, weaving a compelling narrative through abstract pieces of poetry; meanwhile, the flashing words of Rain on the Sea forces the reader to take in the story behind the poem almost more quickly than they are able to. In my piece, I tried to capture the fragile nature of Strickland’s piece, while drawing inspiration from Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries’ quick-moving text in order to capture and keep the attention of my audience.

The topic of cinema writing was another very helpful source of inspiration for my piece, particularly the app Pry by creative media studio Tender Claws, as well as in-class discussions of using shots and montage to create projective, imaginary, and even narrative space. My intention was to employ the unedited daylight shots in such a way that the audience feels they are driving with the character, following her in her flight, within a created space; the more heavily edited nighttime shots were designed to create a stark contrast, an imaginary space that provides backstory through internal narrative. I was greatly inspired by Pry’s use of different styles of footage to switch between thoughts and reality, and I tried to echo that by flickering between night and day footage, showing how my poem’s subject is flickering between what she’s seeing and what she’s frightened of. I added and layered several copyright-free audio pieces from YouTube in order to further heighten that dualistic atmosphere.

In order to create draw all of these pieces together—ideas, inspirations, footage, sound clips, and original poem—I drew a rough storyboard, then created a script that outlined what effects and shots were to pair with which lines. After finding similar footage from YouTube to what I had in mind, I used Adobe After Effects to begin animating my writing. Inspired by David Jhave Johnson’s 3D focal words, I left the opening line ‘she drives’ as a static line throughout my poem, with ‘RUNS’ overlaid onto ‘drives’ during the night footage for added emphasis on the character’s emotional state. While I did use some effects such as curves and posterize on my footage, the text effects were all done using ‘source text’ keyframes. The night footage was shot driving through Portland, mainly on the I-5, while the daytime footage was shot on the I-5 northbound near Castle Rock.

Overall, this was an intriguing and educational exploration into kinetic and cinematic poetry. While I still have a lot to learn about the field of electronic literature and digital poetry, I am proud of what I have accomplished with this project.