“Taroko Gorge” by Nick Monfort is an example of a poem generated by a computer, or combinatory poetics, as outlined in the Electronic Literature Organization’s list of existing electronic literature practices as part of their definition of E-lit. It fulfills John Cayley’s short definition of E-lit as it is “writing in networked and programmable media” and is primarily an example of writing in a programmable media. It also a good example of Stephanie Strickland’s definition of E-lit, which she says

“Taroko Gorge” by Nick Monfort is an example of a poem generated by a computer, or combinatory poetics, as outlined in the Electronic Literature Organization’s list of existing electronic literature practices as part of their definition of E-lit. It fulfills John Cayley’s short definition of E-lit as it is “writing in networked and programmable media” and is primarily an example of writing in a programmable media. It also a good example of Stephanie Strickland’s definition of E-lit, which she says

“relies on code for its creation, preservation, and display: there is no way to experience a work of e-literature unless a computer is running it –reading it and perhaps also generating it,”

“Taroko Gorge” could not be read and would not exist without a computer generating it.

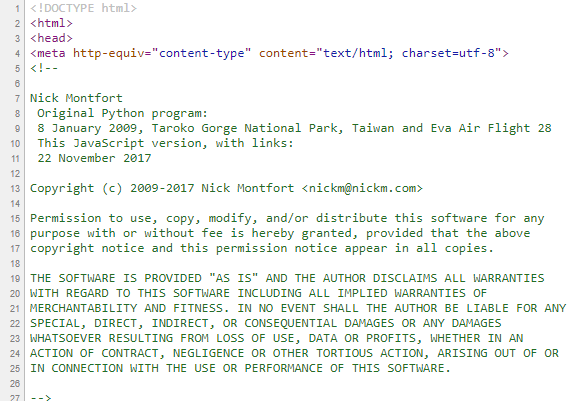

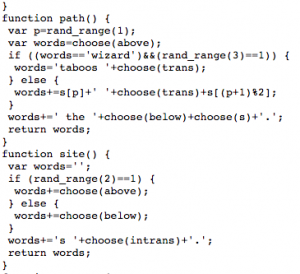

“Taroko Gorge” was originally created in Python and then recreated in Javascript so it could be viewed in a browser. The poem is created by first announcing in the program a series of lists of words, which are then returned randomly in an order determined by the type of list they are in and displayed in phrases that create a poem. “Taroko Gorge” is what N. Katherine Hayles would call “born digital” and each iteration of the poem is unique. Every instance of the webpage will return a different poem than the last. The piece is not only “not easily produced or consumed in print literary contexts” as Scott Rettberg describes in the reading, but it is impossible to produce or consume as print. One iteration of the poem could be printed and distributed as print, but the intention of the piece would be lost.

The piece is a straight forward example of combinatory poetics. Scott Rettberg describes combinatory poetics as programs that “access and present data… and then through algorithmic processes, modify or substitute the data.” “Taroko Gorge” uses Javascript create lists of data, words in the poem, and select and present them randomly to form a poem. This is a similar process to the recipe for a Dadaist poem Tristan Tzara describes, cutting words out of a newspaper and gluing them down randomly as you draw them from a mixed bag. Combinatory poetics uses computer programming languages to create Dadaist poems instantly.