I found myself enjoying a lot of these works, but two that stood out to me were SOFTIEs by David Jhave Johnson and Shy Boy by Tom Swiss.

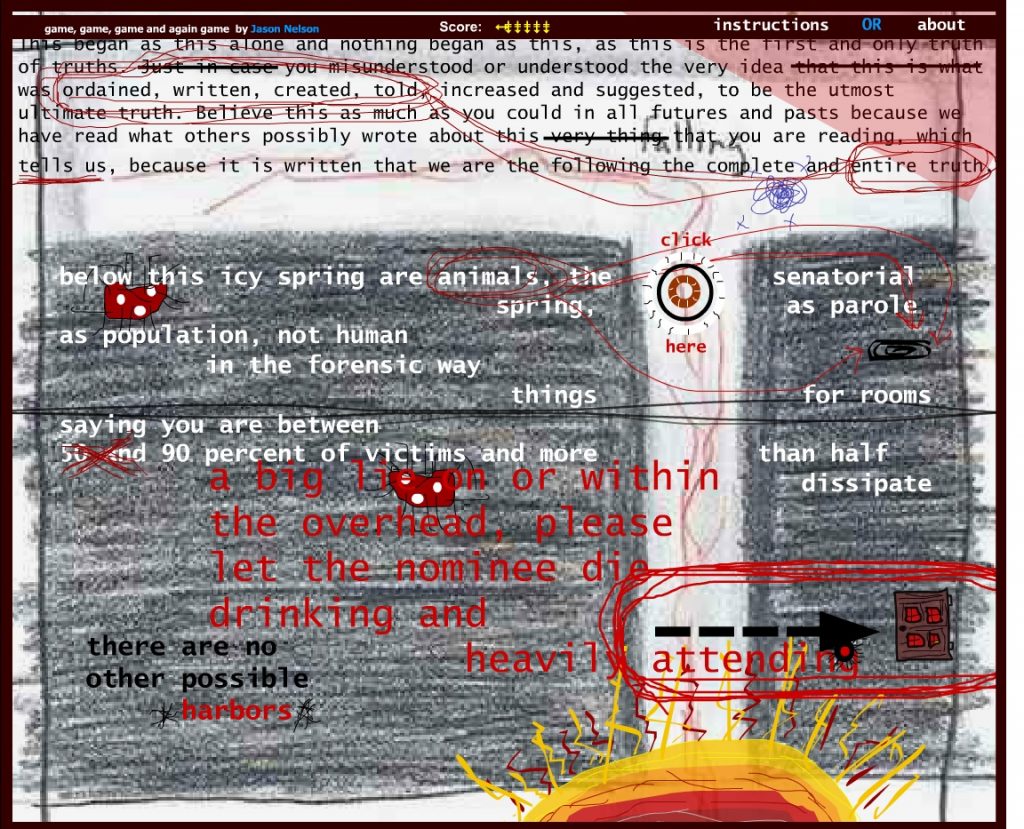

Johnson’s use of movement in this piece is what made it so intriguing to me. I was immediately drawn in as I viewed the first poem on the page. He describes Stand Under as a “social-synaptic structure emulated in language” which I think perfectly describes it. As I clicked on each image and viewed the animations, I felt a deeper understanding and connection to the text.

“Kinetic poetry by definition deals in time-based poetics: its main distinctive characteristic is that texts change through animation, and that animation itself conducts meaning.”(Rettberg, 119)

I think that SOFTIEs is a prime example of how animation of text conducts its meaning in this type of poetry. While I was experiencing this work, I would read the poem first, then would view the corresponding video. Initially, I found some of the poems to be confusing as a stand alone, however they made more sense to me after viewing the videos. Johnson’s use of movement illustrates the symbolic meaning behind each one of his poems. I thought this work was absolutely beautiful.

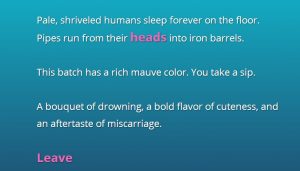

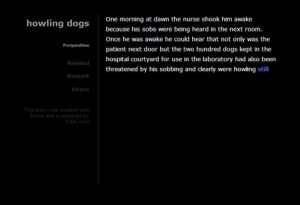

The other work that I took a closer look at was Shy Boy by Tom Swiss. As with SOFTIEs, I also found the movement of the text in this piece offers the user a deeper understanding of the text. The story is about a school boy who can’t bear his current circumstances and longer. The movement of text illustrates the boy’s feelings of hopelessness and desire to vanish. At one point in the story the word ‘vanish’ does just that, it vanishes. The use of animation actually illustrates what the text is trying to communicate. I also found the music that is played in the background played a role in how I experienced the piece. It sets an almost ominous tone that I feel like purposely makes the reader feel a little uneasy.

I think that both pieces were very effective at using kinetic movement to enhance the experience and help communicate the message.