For this post, I will be analyzing Howling Dogs by Porpentine and Galatea by Emily Short. Porpentine’s work imposes ideas of struggle and hopelessness by using darker tones. Through artful writing, Porpentine engages the imagination by painting gloomy pictures with words. Though she experiments with a range of themes by including multiple narratives within the story, they all imply a darker message. The work is also engaging because she utilizes various techniques that help move the narrative along, which Rhettberg states can be represented

“through shifts of narrative voice and point of view… pacing… use of grammar, and its patters of association.” (Rhettberg, 56)

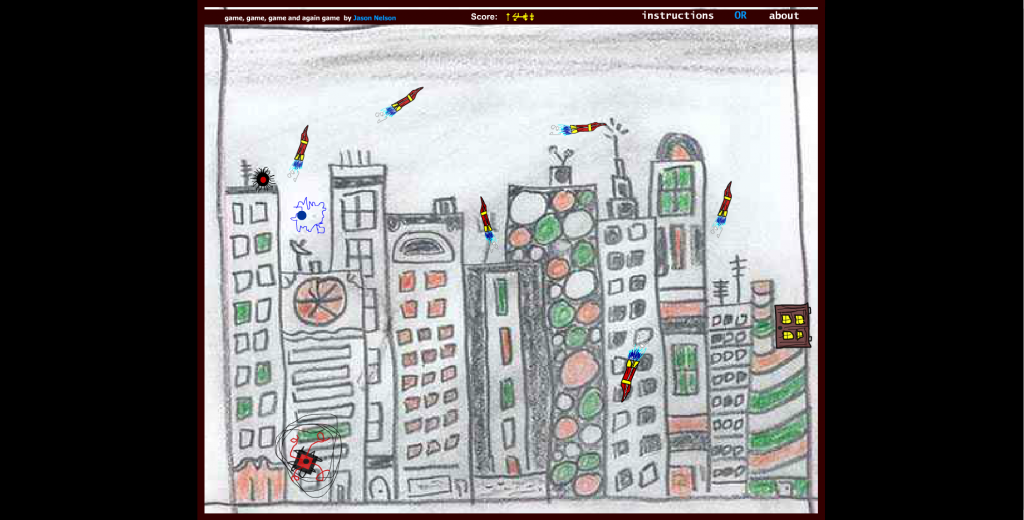

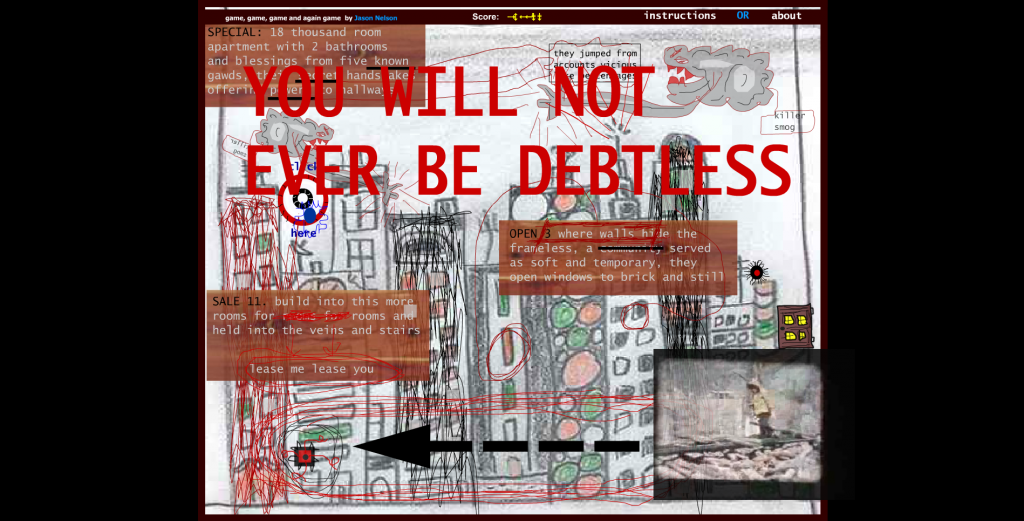

In addition, Howling Dogs portrays struggle and hopelessness by presenting repetitive actions and responses to the user. Despite the player’s attempts to improve the quality of their character’s deteriorating life, the drudgery of the same daily routine eventually takes its toll on the users, who lose hope of finding any meaning within the story besides the themes I listed. A third technique Porpentine uses is offering limited options when it comes to navigation. Users can only click on the hyperlinks shown on screen, limiting their ability to explore the world freely. By utilizing repetitiveness, a dark tone, and limited freedom for exploration, Porpentine imposes ideas of struggle and hopelessness upon the user.

However, Emily Short utilizes interactivity and exploration to portray hopeful ideas. Because Galatea is an interactive fiction, players can enter their own commands, involving them more deeply with the story’s possible meanings. In addition, Galatea’s personality and reason for existence are not initially specified, offering the player power over determining these factors through the dialog choices they make. And when Galatea relates her personal experiences to the reader in fragments, the player is further engaged by trying to put the pieces of the story’s puzzle together in their imagination. By allowing players freedom and providing a complex NPC to interact with, Short portrays the idea that fate is not predetermined, while simultaneously encourages them to seek out conversations and establish new relationships.

One similarity between these works is the lack of a player “goal”. In Howling Dogs, the player merely watches on as things decay around them. And in Galatea, the player simply speaks to Galatea until some conclusion is drawn. The works are mainly focused on using their frameworks to explore literary ideas. Porpentine’s goal was to experiment with presenting multiple narratives to the player that were different yet cohesive to the story. And Short’s goal was to explore the potential of NPC interaction as a deeper, more complex process.

To conclude, both Howling Dogs and Galatea utilize varying levels and modes of interactivity to get their messages across. Despite being so different, I found both works equally intriguing to explore.

Over the years, hypertext has been non stop evolving. With

Over the years, hypertext has been non stop evolving. With