internet-x.smvi.co

Social Media SV Site

https://small-victories-folder.smvi.co/

Made by Courtney, Katya, Ian, Mallory

“Social Media usage”

🙂

Small Victories

https://genetically-modified-parrot.smvi.co/

Jazz Jackson

Joel Cummings

Jarid Schoenlein

Shawn Sims

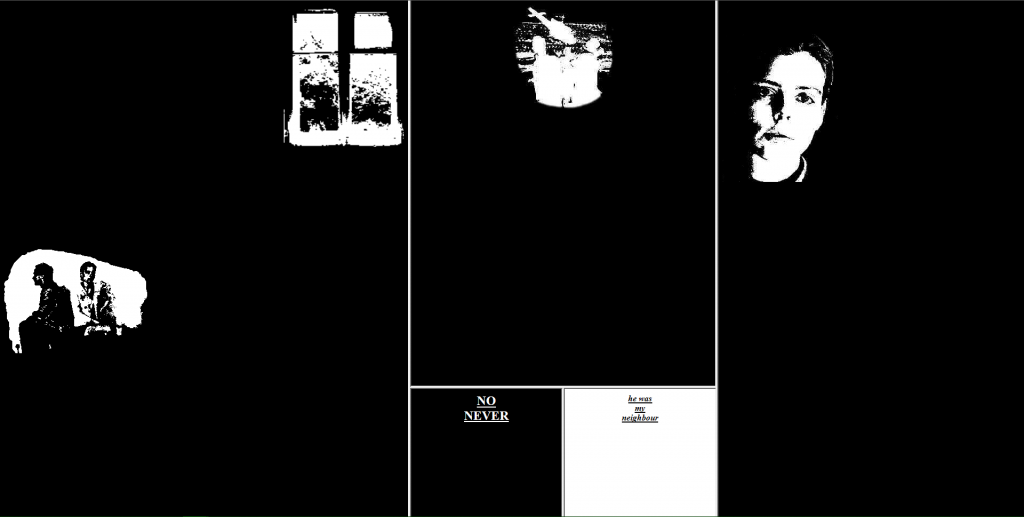

My Boyfriend Came Back From The War

What I really liked about the story “My Boyfriend Came Back From the War” is the story. From what I can gather of the story it appears that the story is that the boyfriend comes back from the Gulf War, and him and his girlfriend are sitting next to each other, with their backs turned. Neither are looking at one another which is a powerful image that really sets the tone for what is to come. The use of visuals in general is incredibly important and well done. I like how on the right is the girlfriend and on the left is her boyfriend who returned from deployment. Between them is a frame, which (I may be reading into this) I argue signifies the rift that has been created, as displayed by the fact that there is a picture of a helicopter off in the distance; representing how war has ultimately created a rift between them. Her cheating on him also creates that rift.

One of the things I noticed was that as the dialogue progressed, the frames continually grew smaller and smaller, this was pointed out in Net Art Anthology’s piece about this hypertext story. Like what was discussed above, this fragmentation serves as a way to further represent the breaking down of the relationship between the two of them.

What is nice is that unlike earlier hypertext stories like Victory Garden is that it isn’t huge walls of text. Olia really utilizes the visuals to tell the story, the dialogue is more an addition to it all. Olia could’ve just used visuals alone and I argue that the general story would’ve been just as easy to follow.

The only issue I took was with the ending, because it doesn’t show who is talking I had a hard time figuring out who was talking and who was not.

Does Net Art Equal Net Difference From Hypertext?

Farinsky Blog 4: Net Art

“My Boyfriend Came Back from the War” by Olia Lialina is work classified as net art, but looks incredibly similar to hypertext fiction. To read this work you click on links which subdivide the screen as each story path propagates new text and images. One significant difference seems to be that all the narrative paths seem to stay on screen, and accessible to the reader, unlike most hypertext which rarely gives map, or an overview of where the reader is.

Like hypertext “My Boyfriend Came Back from the War” carries many linear narrative paths that exist at the same time. Each segment of the screen represents one path, and divides to show complexity quickly as one box becomes 2, 4, or 8 as represented by the image above. It is overwhelming to track each piece but still intriguing as the narrative plays out in the reader’s imagination and on screen through snippets of dialogue. The pace of this story is quick- often boxes contain less than 15 words so reading and clicking the next link is significantly less spaced than typical hypertext works. It reads like a conversation by mirroring the speed of a in-person dialogue.

Perhaps net art and hypertext are the same thing, but only separated because they did not exist within platforms such as Story Space like many other famous works of hypertext fiction. If what truly separates net art from hypertext is self publishing through java script perhaps a better name should be “independent hypertext” rather than “net art”. Calling this type of work net art leans credibility away from connotations of the word “literature” because they resemble art with literary features just as much as hypertext resemble any traditional example of literature. Self-publication of a book or a website is significantly different than going through a traditional publisher or using a program with prescribed layouts to create stories however it is not necessarily different enough to call the product a separate entity if publication method is the only significant difference as it appears here.

What is Grammatron?

I spent hours last night, lost in the surreal world that is Mark Amerika’s Grammatron. Not knowing how to approach this unique piece, I did the only thing I could think of and dived right in. I looked at the “about” page, clicked begin, then clicked the first link I was prompted with, marked ‘high bandwidth version,’ because heck, compared to the internet of ’97, I should hope my rig will hold up. A new window pops up, blaring surreal synth music and artificially altered vocals, I’m redirected to a web page with bright, clashing colors, distorted cyber-punk images, and text that appears just a little faster than I can comfortably read them. The assault of strangely retro-future-cyberspeak and neologisms, along with trying to process the unusualy pictures and understand the voice playing in the background, created an uncomfortable disorientation as my brain struggled to keep up with all the information being presented. Then just when I became accustomed to it, it stopped…

The rest of my experience with Grammatron what, in comparison to the previous multi-media onslaught, could be called a more traditional HyperText experience. Text appeared on the page in front of me, only periodically punctuated with images and audio. The blue hyperlinks in the text prompted me to continue the narrative, but as I struggled to understand the meaning of the words in front of me, I found myself clicking links randomly, hoping to progress the story in some way and hopefully find clarity.

The text seemed to circle in on itself, never quite the same, becoming more legible as time went on. Looking back, I’m unsure how much of the actual text changed and how much of it was merely my perception with my growing understanding of the strange world of Grammatron. My previous experiences with kabbalah and cyberpunk tropes helped me little at first as I attempted to reconcile the metaphysical and digital aspects of the story, as well as the overtly sexual aspects of the narrative. But sure enough, it started to make a strange sort of sense.

The next day, I’m looking back and trying to remember my experience going through Grammatron. The details of the narrative still seems largely unclear to me, as well as the finer aspects of the world-building. What I’m left with is more an impression, an impression of being lost in a sensory whirlwind, a struggling for clarity that seemed to mirror the bizarre protagonist.

HyperText fiction has a unique ability to allow us to tap into and interact with the experience of a story. In Grammatron, the viewer is thrown into the stream-of-consciousness of Golam’s inner thoughts. The use of multi-media, both audio and video, are made of excellent use to help reinforce this. Although chaotic, the experience is certainly carefully constructed, and I know I’m hitting just the tip of the proverbial iceberg.

Grammatron and Structure

Line 2 c of the definition of net.art created by Natalie Bookchin & Alexei Shulgin describes net.art as:

By realizing ways out of entrenched values arising from structured system of theories and ideologies

This single line in the definition of net.art could be extended to include many different types of electronic literature.

The non-linear nature and aspects of variability enabled by electronic literature allow for the deconstruction of structures that are used to signal meaning in other types of media. A typical movie will follow a paradigm, a structure that signals to the viewer when certain aspects of the story are important and why. The viewer knows they will first be met by an exposition, and they expect a resolution at the end, with interest and conflict in between. Many movie critiques center around whether a movie met this structure, and if it signaled what aspects of the story the viewer should take notice of by using structure. Electronic literature often makes no attempts at helping the viewer make sense of the content. The unsatisfying nature of many pieces of E-lit is what spurns the reader forwards in the story, making the consumer work for the meaning the author has embedded in the work, rather than presenting the meaning in a structure the viewer is familiar with.

Grammatron is an example of net.art that makes no effort for the reader to make sense of or even be comfortable with the piece. Grammatron refers to itself as a writing machine, introduces a creature, an image of a nosferatu-esque face covered in text, mentions the concept of gender, and displays text that creates the illusion of self-awareness. An eery audio files appears in a popup upon beginning the traversal, and the aspects of the piece, the writing machine, the creature, and self-awareness, are gradually revealed in the beginning, but in different orders from traversal to traversal. Grammatron does not prepare the viewer with what the content will be about. The piece and the authors description of it in the Mark Amerika article are deliberately vague. Net.art, like much of electronic literature, makes no effort to be palatable or sense-making to the reader. Net.art demands that the viewer be invested and investigate the E-lit to reveal the meaning of the piece and create the viewers own unique understanding of the experience.

My Boyfriend Came Back from the War

While I’ve explored all of the works presented to us for this week’s blog discussion, I’m particularly intrigued by Olia Lialina’s work “My Boyfriend Came Back from the War”.

One distinct feature of Lialina’s work in comparison to other hypertext fiction works is that it is far more linear and finite. Each link will only bring about a few more options for one to click on before the link disappears, forcing the reader to move on to the next link of their choice. Additionally, my personal experience in regards to navigating through the work led me to read it in a similar way time after time, due to the fact that the entire work laid out on one screen and my natural inclination was to navigate through the work from left to right.

The defining feature of “My Boyfriend Came Back from the War” that sets it apart from other works of hypertext fiction is Lialina’s use of animated and still imagery to enhance the story. As stated in the Net Art Anthology article in regards to the work,

My Boyfriend Came Back from the War highlights the parallels and divergences between cinema and the web as artistic and mass mediums”

Lialina does an excellent job of incorporating imagery into her work by both maintaining certain images on the page throughout the work, as well as by creatively turning certain images into links that lead either to other images or to text that progresses the story further.

How my Boyfriend Came Back From the War is set apart

In My Boyfriend Came Back From the War, Lialina immediately captures the user’s attention with the affordances hypertext provide. People who are used to print might be thrown off by the black background with white text. Combinatory poetics are used greatly. The story is organized by several boxes that each contain their own string of dialogue or thought. When the user clicks on a box, the next phrase appears. As the about page points out, the user can click on the boxes in whichever order they want, thereby putting the user in a spot where they potentially must memorize the content of several boxes at a time. This personally makes me interpret the structure of work as something akin to the person’s mind constantly jumping between several thoughts when they meet a person they care about for the first time in a long while. The images used are reflective of the author’s present situation and those like the clock and 20th Century Fox logo are symbols. It’s important that many of the images are also things that can be clicked on, oftentimes appearing instead of text. Images aren’t used to compliment the story, but also partly tell it. This and the other works differ from earlier hypertext by being quicker, having more variety in their content, and being free to access online.

“With its use of browser frames, hypertext, and images (both animated and still), My Boyfriend Came Back from the War highlights the parallels and divergences between cinema and the web as artistic and mass mediums, and explores the then-emerging language of the net.”

A look at World of Awe

In reading World of Awe, the way it is presented made me think of the old CD-ROM games I used to play as a kid. Following the journey of “the traveler” the reader is bounced from first-person accounts to letters he has written to a lover. Also one gets the sense that technology is very precious in this fictional world, as the traveler seeks out any piece he can find, in this virtual desert.

I did find it extremely helpful to read the “about world of awe” piece, because there were some parts of the reading I was unsure of, and it was able to clarify certain plot points. Like the fact that the letters on the computer were unsent, to the traveler’s unknown lover. In the first chapter, he speaks about this person with great yearning, saying how he carries around a piece of cloth of their’s just for comfort.

The intertextuality between this piece and Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse is what caught me. They both are fragmented looks at a person’s life. Although personally, I preferred World of Awe to Funhouse. The story is easier to follow, and maybe it’s the 90’s kid in me but I liked the format, it definitely felt familiar and nostalgic.

This is not a story that has much variability unless one chooses to read the chapters out of order. Which with most of the readings so far that has been the case.

The artwork I think is a key part of telling the story, it adds another layer of understanding with these visual references.

Overall, I really enjoyed this piece.

My Boyfriend Came Back from the War

I chose to go more in depth with the work “My Boyfriend Came Back from the War” because it seemed to have peaked my interest the most and I’m glad that I read it. It’s just a simple story by Olia Lialina and supplies a lot of the HTML elements to it. The story is told through the narrative of two individuals, the girlfriend and the boyfriend and it’s about the two lovers reuniting after the boyfriend came back from the war. The story uses, what looks like to be, old school pictures and still images to tell the story as well as a kind of multilinear structure that when you press on a fragment it splits in half and gives us two choices on what we want to do in that situation.

“Lialina aptly uses the web to interrogate our understandings of the production and organization of memory, a question that structures her practice to this day. In keeping with this, she considers the numerous artistic remakes and remixes of the piece an extension of her initial investigation.”

I felt like the story taught us that even with an incomplete story you can still finish it, just opening you imagination and open your interpretation on the story piece. The themes that I found behind this work was really intriguing. I saw that there was pulsing imagery with the window as well as intertitles after each of the splitting images. One last thing that I would like to touch up on is that I felt like this story is really sending us a message but the problem is I don’t really know what message it is; it could be that were still at war in the middle east or maybe the fact that war changes people, once the individual leaves they will not come back the same person. Like I said… open to your interpretations.

World of Awe

When I was reading each of these pieces I had so many different reactions and emotional responses. When I first read Grammatron, I was mostly just confused but with both World of Awe, and my boyfriend came back from war I was enthralled. The ability to have your reader interact with the piece allows them to feel more engaged. When I was going through World of Awe I really did feel that sensation on loneliness and wandering as well as the need to find the treasure. The ability to click around the desktop and look at the love letters then move back to the “journal” allows us as the readers to set our own pace. The use of multilinearity in all of these pieces in interesting, when looking at world of awe it is multi linear due to the different places you start from like with the love letters or with the actual notes or even with a different chapter. When you look at My boyfriend came back from the war it is much more open by each ‘window/cell’ that you can click on is a contained thought. While in conjunction working with the cells around it this kind of path I overall linear but you will most likely find yourself going through this piece slightly differently every time. The way that each piece has addressed hypermedia, and net art covers vastly different but they all share on thing in common, the digital space.