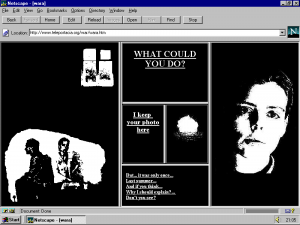

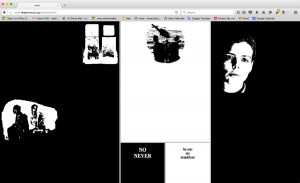

Olia Lialina’s, My Boyfriend Came Back from The War is the net art fiction I chose to read. Lialina’s net art fiction differs from the hypermedia styles, such as multilinearity, variability, combinatory poetics etc. She uses elements of HTML to convey a cinematic story. Her work of hypertext fiction tells the story of a young woman reuniting with her boyfriend after he returns from war. She uses browser frames, hypertext, and images. Lialina wrote her fiction is in a style she calls net language. Lialina states, “If something is in the net, it should speak in NET.LANGUAGE” The net. language style is emphasized in this work which stray amid cinema and the web as creative and mass mediums.

I like the interaction between the still and animated images. I feel that the interplay between the text and the images helps create a cinematic feel. It’s almost like watching a silent movie. I think it is interesting that the reader advances the story by clicking on hyperlinked, disconnected expressions and pictures. With each click on the picture or text, the browser viewport splits into several smaller frames. I did get a macabre haunting feeling from the still and animated images. This style of hypertext fiction works to really create a ghoulish mood. I actually thought story was going to go into a dark territory. Lialina’s work keeps the reader involved by using images to create tension. I kept clicking on the text and pictures, because I thought the boyfriend was going to return to his love damaged from the war.