I really enjoyed most of these pieces–even if I didn’t like the plot exactly, I appreciated the medium. My favorites, however, were HeyHarryHeyMatilda, The Fall of the Site of Marsha, and I Love Alaska.

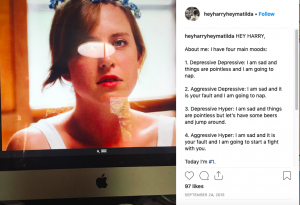

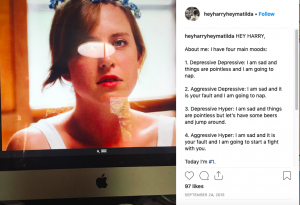

HeyHarryHeyMatilda was interesting not only for the plot (which wasn’t fantastic but was still fun to read, in my opinion) but for the way it utilized Instagram. I don’t know if I would call it a full ‘novel’ (although the author did publish an actual novel of the story) but it did weave a compelling narrative as well as made me pause and wonder what story I am telling with my own social media accounts.

HEY HARRY,

I think you’re right. I get the signs but not the message. I’m like a highly attuned, extremely useless oracle.

I like this quote in particular because it reminds me a lot of how most people interact with social media. We see what’s on it, but not always how it all fits together to form our stories (or at least, the stories we send out to the world).

I did think that it was a bit of an odd choice on the author’s behalf, however, to compose the story in the form of emails posted as Instagram captions rather than simply Instagram posts. Obviously, that would have somewhat changed the dynamic of the piece: two twins sharing one Instagram account rather than exchanging emails. I guess Harry would have to have given Vera access as well, which does differ from Vera just getting Matilda’s email address…but I think it would have strengthened the usage of Instagram as a storytelling medium.

That said, I liked how the author interacted with commenters as Harry or Matilda, as if they really were the ones running the account; it gave it a realistic and modern depth in a way that a paper novel is incapable of. I also started noticing a few commenters creating friendships and even weaving their own little storylines in the comments, which was fun to see. I’m not sure how fictional or otherwise these commenters were, but it was an interesting branching of the narrative that I bet not even the author predicted.

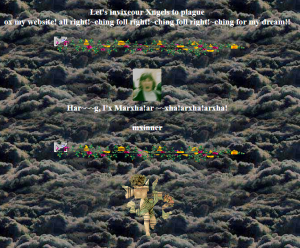

The Fall of the Site of Marsha and I Love Alaska were both interesting because they were both about humans turning to the internet to cope with their tragic (or, as some might see it, maudlin) lives. I liked The Fall of the Site of Marsha as a statement, a story, and in an aesthetic sense: I thought it was really impressive how a single website with just a few pages gave such a sense of character. I took the Throne Angels and their interactions with Marsha as a metaphor for the dangers of using the internet as a crutch–even as a kind of false faith. I also enjoyed the website being broken as a visual for Marsha’s life falling apart. With I Love Alaska, I thought it was a bit more poignant since it was a real person and not a fictional account, although I didn’t actually like the woman herself. I thought it was another interesting example of how we turn to the anonymity and perceived safety of the internet in times of stress or other negative emotions, as well as the dangers of those actions. A person turning to the internet for comfort can easily be abused, as in Marsha’s case, or revealed unexpectedly, as in the case of User 711391.

As a side note–I liked the website Degenerative, too, and thought it was a pretty neat concept. However, when I click the ‘read more’ button on the first page, it takes me to http://www.motorhueso.net/degenerative/about/ which reads ‘Hacked by Nero Hacker!’ It doesn’t seem to fit with the rest of the piece, so I think it really was ‘hacked’ by someone? Or am I misunderstanding something here?

From Rettberg’s reading, the main thing I was looking for when exploring the sources for this week was some the collaborative elements that he described for network writing.

From Rettberg’s reading, the main thing I was looking for when exploring the sources for this week was some the collaborative elements that he described for network writing.