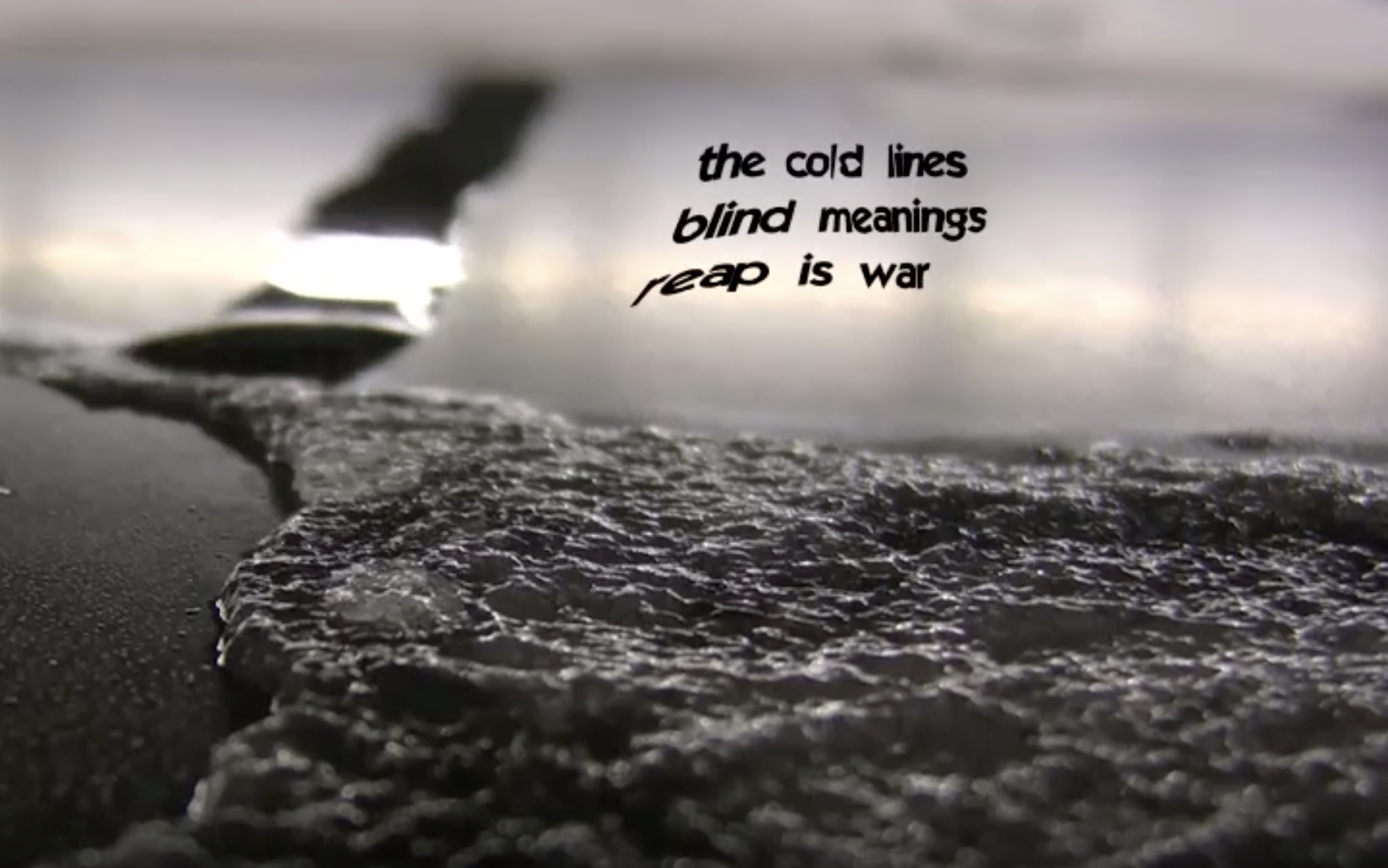

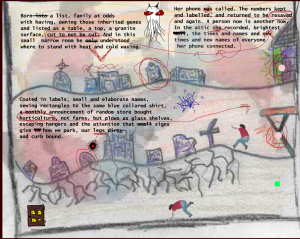

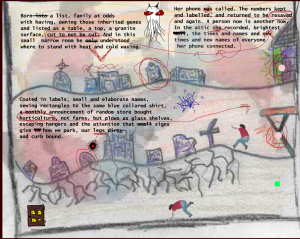

Game Game Game and Game Again by Jason Nelson has caught my attention like no other piece of electronic literature so far. Game again is a narrative game that combines elements of a video game platformer with poetics, strange sounds and visuals, and video clips. The platforming was actually quite fun and unique at times, especially for a flash game focused on narrative. I have to say that Game again is the most bizarre, strange, and straight up creepy flash game I have experienced on the web, and that says a lot.

I felt like I was playing something that was created by an insane person as I was bombarded by strange sounds, visuals, and pieces of text that did not make too much sense. The whole thing had a disturbing, almost otherworldly feeling. The game encourages the user to find meaning by placing different objects to reach within each level. As an object is collected, it reveals a piece of text. Within many levels, a clickable button will appear that plays a short video clip on repeat. Overall, despite the disturbing aspects of Game Again, I would have to say that its combination of platforming, visuals, video, and text are incredibly engaging and impressive.

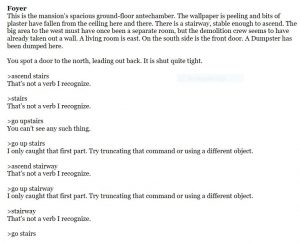

I then decided to explore With Those We Love Alive by Porpentine. This game is quite different from the previous one that I explored, as it is a text-based adventure, much like Zork, except the user clicks on words instead of typing their own. The game also has a soundtrack which I found to be quite nice and relaxing, it made me feel much more immersed in the experience. I actually quite enjoy text-based games as they allow you to visualize a world in any way you wish because, in reality, the author is just providing guidelines of how the world looks; it is up to the reader to create their own details and interpretation of the world.

Providing music can help influence the way in which a reader visualizes a world. The music in this game had me thinking of a beautiful, serene palace instead of one that may be old and run down. This is interesting because the story actually takes place in a world where a larval empress has you working for her in a dingy palace, but the background colors and music make me think of this serene place. The game also allows the user to change words in the story by clicking on them. For example, I had to make a gift for the empress and I did so by clicking on words to change them to create a gift. At this point, the music changed to something more strange and sinister but returned to its relaxing form after I returned to the palace.

Both narrative games I explored are incredibly different in nature. Game Again relies heavily on visuals and gaming aspects (platforming) while With Those We Love Alive is a purely textual experience. Game Again felt more like an on-rails experience, as the goal was to get to the end of each level while collecting things along the way. The game bombarded the user with strange sounds and visuals to create a confusing and disturbing atmosphere. With Those We Love Alive is a non-linear experience that allows the user to take their time and explore the world at their own pace. It has atmospheric and relaxing music, but also has depressing and dark themes, but overall it is a much more muted experience than Game Again.