It’s hard for me to say what I think the future of hypertext fiction will be. I don’t think it will die out, as there will always be people and pieces of work that will keep the genre alive. I do however, think that it will dip in and out of popularity as the years go on and as more technology is developed. In the past, hypertext fiction is something that has repeatedly grown popular for a short while, only for it to die down and come back again later. The best example I could come up for this is the company Telltale Games, a gaming company that exclusively creates “Choose Your Own Adventure Games”, or works of hypertext fiction. This company became increasingly popular a couple years ago, to the point of creating stories for big names and other game companies. The Walking Dead, Minecraft, and Batman are a few series’ who got their own Telltale Games. Although all their games got generally favorable reviews, and fans loved playing them, on September 21st, an announcement was made that Telltale Games would be shutting down. The reason? Not enough people were interested in and buying the hypertext fiction genre of video games. Unfortunately, no matter how well something is made, if there isn’t an audience to watch/play/listen to it, then it becomes unprofitable and will come to an end.

I really enjoy hypertext fiction. I like the idea that you decide the outcome of the story, and that your choices truly affect what happens. I do think for a work of this genre to be enjoyable, it needs to be done the right way. If there’s too many or too little options, or the story becomes so meddled and confusing that there doesn’t seem any point in continuing, then it becomes more work than enjoyment. Since a story with multiple storylines can be difficult to properly write out and execute correctly, I feel like this is the image that hypertext fiction often gets. Like I said before, I don’t think hypertext fiction is going to die out (at least anytime in the near future), but I also don’t think it’s going to get extremely popular in the near future. Even newer medias such as Bandersnatch seem to have excitement for a few weeks, and then the whole genre gets lost in the depths of the internet again.

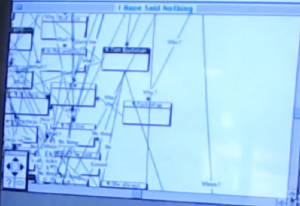

Hypertext definitely goes somewhere that regular print cannot. Print books in the past have been “Choose Your Own Adventure” books. However, the constant flipping of the pages, and navigating through the big piece of text is a lot more frustrating than just being able to click on a particular link in a story and get to the next point. If one were to create a hypertext fiction piece of work, I think most of the time one would lean toward creating it on a digital medium. The evolution of technology and hypertext as one have created this genre of fiction that is compelling, exciting, mysterious, but unfortunately, not very popular.