Bill Bly is the author of the hypertext novel, We Descend (Eastgate, 1997) as well as many poems and stories that have appeared in 5 AM, Amelia, American Poetry Anthology, Antigonish Review, Encore, Explorations ’95, MacGuffin, Runes, Yahoo! Internet Life, and Zone 3. He has published articles and reviews in such publications as Barron’s Book Notes, sigWEB Newsletter, Books & Religion, Didaskalia, TDR, Tekka, and Trinity News. He teaches writing at the university level and has taught at New York University, Fordham University, and Wagner College, where he ran the Writing Program. He has won the Stanley Drama Award, held writing residencies at Shenandoah Valley Playwrights Retreat, Ploughshares International Fiction Seminar, and Vermont Studio Center, and received fellowships from the Shubert Foundation and the Empire State Institute for the Arts.

Artist’s Statement

Almost three decades ago, while I was doing something else, five words dropped unbidden into my mind: “If this document is authentic…” I tried to keep at what I was working on, but the phrase kept repeating, until I finally turned my attention to it.

Who’s saying this? I wondered. What document? Why wouldn’t it be authentic? How would it be authenticated? Where did it come from in the first place? As I pondered these questions over a period of time, a clutch of fragmentary writings began to appear under my hands.

Almost from the beginning it was clear that each of these texts bore a double significance: each told a story, but each had a story as well. Further, their transmission as a group formed yet another story: their possible origin in some personal collection that was passed on, lost, found again, added to, broken up and scattered, all but destroyed, then miraculously pulled together again. Eventually, what came to be called We Descend took the shape of an archive of archives, an anthology of writings by numerous authors, which had been gathered and repeatedly reorganized, passing through the hands of many generations.

Every time a new Writing turned up, those five first questions crowded in along with it, followed by a cloud of proposals, conjectures, romantic imaginings — each provisional solution embodied in yet another Writing, whose own provenance had to be established or at least guessed at. Successive curators of the archives must have tried to organize and present them in whatever way seemed best, given the circumstances and the tools each had at hand. And so I tried to do the same.

I was unaware that, while this was happening at home, another community of authors and scholars, all engaged in writing and theorizing literature that somehow exceeded the bounds of printed text, had begun to gather in the world outside the window over my writing desk. At the time I did not own a personal computer — if I even knew about such a hopeful monster: my gear consisted of a pad of paper, a fountain pen, and a clipboard to keep everything together, as well a typewriter for later making what I scrawled in ink decipherable for anyone else to read. (This rustic mise en scène was all too soon to be savagely disrupted — a wrenching operation that still cycles madly.)

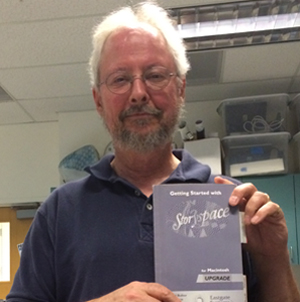

When, in a fit of intrepidity, my wife and I bought our first Macintosh SE (talk about quaint: a family computer!), I became intrigued by a freebie program called Hypercard, and started working up ways to employ it to help me keep track of the various resources every teacher needs in order to ply the trade. Not long afterwards, Robert Coover’s revolutionary essay, “The End of Books“, appeared in the New York Times Book Review, in which he told of a new way of creating literature, something called hypertext — which “provides multiple paths between text segments… [and] webs of linked lexias, [with] networks of alternate routes (as opposed to print’s fixed unidirectional page-turning). [Hypertext] presents a radically divergent technology, interactive and polyvocal….”

Spellbound as I was by terms like “multiple paths”, “lexias”, and “polyvocal”, I only vaguely understood what he was talking about, though somehow I was absolutely certain it was important. And as I found out more about hypertext, it didn’t take long for me to realize that my work in what I was still calling just “the archives” — with its many voices, criss-crossing plotlines, and multiple bands of time — could only fully tell its story if it were rendered into hypertext form. This meant that the time had come to completely overhaul my modus scribendi, which, until then, had been conducted in the conventional way, by rummaging in piles of scribbled-on pieces of paper, then scribbling some more.

To render what might be called hand-text into hypertext entails a lot of pondering: of text, now that it’s hyper; of writing in the first place; and of the reader an author addresses when writing, and by addressing conjures. I’ve come to think that this person, the reader, is as real as any person I hold in my memory. It’s no use insisting there’s a distinction between real and imaginary here: every person is imaginary who is not right there in front of us (and even that person is a hybrid of real and imaginary attributes).

Writing of course means encoding: it packs up and jams our experience of life into little suitcases made of words, to cite one especially fractious Author in the archives. It generates text, a magical… — well, what kind of a thing is text? Is it real or imaginary? is it matter or mindstuff? meat or ghost? It just won’t do to blow off these essential questions by saying, “It’s both.” That doesn’t answer the question: it deepens the mystery.

There are pleasures in life that simply cannot be had by solving a puzzle or triumphing over an adversary, and for me, this is one of them: using text to ponder text. And I find hypertext to be the most rewarding vehicle for carrying on that meditation. (My other vehicle is the Mahayana.)

The archives — for which I invented the name We Descend in order to publish the first volume (Eastgate 1997) — constitute an ongoing reflection, not only upon text, writing, and the reader, but upon the scholarly life altogether, a reflection which studies, among other things, what it means to study. To some, the scholarly life, being focused on the past and not the present, is less important than the active life; but the scholar often regards the active life as little more than “fighting one’s way through the pack of others fighting their way”, as another wry Author in the archives puts it.

I sense you, Dear myReader, nodding in sage agreement, for, I believe, you are (are you not? whatever your official job title?) a scholar as well. That being the case, the past is often more present to you than the present itself, which is too full of violence and anxiety to be capable of study, or even deep attention, and that is precisely the pleasure you seek, as you ponder over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore: raptness.

I cannot hope to fully satisfy that longing, if it even can be satisfied, for that would only be another victory, and winning isn’t what we love the most, at least not when we’re a-pondering. For me, the archives have proved rich in the enchantment of scholarly absorption — which may in part account for the absurd delay in getting this stuff out there.

The other part is that new material keeps turning up, at all levels of critication, with the result that a second volume of New Selected Writings is only now nearing completion. Every time a new Writing “appears on the doorstep” (as it seems to do repeatedly for the unnamed Scholar inWe Descend), BBly Renderor must engage in yet another bout of head-scratching and tinkering with the controls, as he labors to incorporate these new Writings into an ever-developing system of hypertext arrangement for the archives as a whole.

And then there’s the tech, which won’t stand still. One would like to think oneself progressive, the type of person who is capable of calmly regarding all developments in digital life and practice as evolution (and not just blooming chaos). But it’s hard to keep up, especially when one takes as long as I do to painstakingly works out a method that — well, that works — and suddenly it can’t be used anymore because the new OS won’t support it. (Yeah, yeah — shut up, Senex, and quit interrupting the music.)

But let us finish this manifesto (O Ludd, another one!) and get back to work. Come the TechnoRapture, all this tsuris will be Left Behind. It’s possible there will be scholars among the entities who enjoy that unfathomable afterlife, and it may further be that instead of gnawing on meat and vegetables, these supernal beings will draw sustenance from the ambrosia of mental life forms that we preserve and thus transmit to them — by means of text, hypertext, peradventure even utterance. If so, what better offering can we make, whilst awaiting the awesomeness of that Very Last Day, than to render our thoughts, hopes, dreams, jokes, stories, theories, and best intentions into every potent medium we can contrive, so that our Dear Reader may have a richer life, and that abundantly?

[Sorry, gotta go update the OS on all my devices…]