The excerpt, below, comes from the keynote I gave at the 2016 International Digital Media Arts Association Conference.

You’re watching a video of Amaranth Borsuk demonstrating Whispering Galleries, a work derived from a diary dating to the 1850s. The work itself is an interactive narrative that allows Borsuk to erase words from the screen by gesturing over a Leap Motion device. Doing so reveals words that comprise a poem. To change the diary’s pages, she gestures a swipe over the device. What you many may not notice right away is that the computer’s camera is capturing her image and incorporating it into the interface of the work, in essence, resulting in her becoming part of the work as she experiences it.

So my questions to you are: How does one preserve a work like Whispering Galleries for posterity? How do we preserve any creative work of art that requires us to interact with it? That involves a media rich sensory experience, involving movement, sound, and gesture that cannot be captured in print? That has been published on and for digital technologies that are no longer available––I mean, how many peripherals like joysticks, game controllers, power gloves have been abandoned because they no longer work for the systems we now use? Leap Motion may very well be another. These are some of the questions that have shaped my research into preservation of electronic literature for the last eight years and that form the topic of my talk today.

Part 1 Why Preserve Visceral Media

Since 1991 I’ve collected a type of digital creative art known as electronic literature. Many of you recognize this art form as digital narratives, kinetic or animated poems, hypertext fiction and poetry, interactive drama, literary games, and many other born digital forms that possess a literary quality and are produced for and intended to be experienced with/on digital devices. To date, I own over 200 of these works in my personal library at Washington State University Vancouver.

Besides being digital, this kind of work is also visceral with viscera associated with the body’s internal organs––the heart, liver, and gut––which are both physical and fragile.

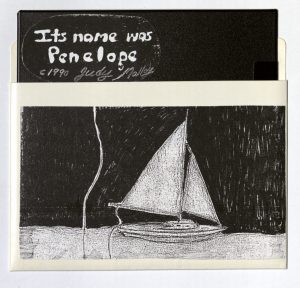

By physical, I mean they’re works that involve kinesthetic activity––that is, they elicit non-trivial physical intervention by the user. Whispering Galleries serves as an example, but so do many others. Even early electronic literature like Judy Malloy’s database novel Uncle Roger, created with Applesoft BASIC and published on a 5 ¼-inch floppy from 1986 to 1988, required users to intervene physically in a non-trivial way in order to access the narrative programmed in the database.

They may also be kinetic, with images being made to move due to physical intervention of the user. Along with Borsuk’s piece, I am thinking here of others, like Jason Edward Lewis’s The Great Migration. Developed as an app for mobile devices, it consists of strange creatures swimming across the screen. When they are “tamped down” by the user’s finger, they writhe and spin in resistance, responding to the user’s touch by emitting tiny bubbles into their habitat.

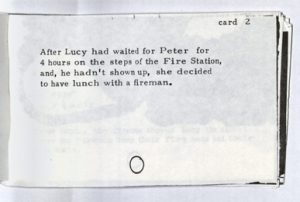

Though Whispering Galleries doesn’t utilize sound, many others do. In fact, electronic literature artists have worked to incorporate sound from very early on. One of the first is John McDaid’s hypertext novel Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse created with Hypercard 2.0 and published in 1993. It came packaged with two audiocassettes that augmented the narrative with musical compositions by the titular character, Uncle (Arthur) “Buddy” Newkirk.

Like Whispering Galleries, they may also produce an embodied experience. Kate Pullinger’s interactive novel, The Breathing Wall, published in 2004 on CD came packaged with a headset whose mouthpiece users breathed into in order to access portions of the story. In effect, it incorporated the user intimately into the work, turning the human body into one of the media of its multimedia.

Also like Whispering Galleries is Erik Loyer’s literary app, Breathing Room, has users gesturing with their hands over a Leap Motion device and so controlling the story with their actions.

. . . And so on and so on and so on. To sum up, visceral media are physical media involving non-trivial user interaction, media rich experiences, and embodied action. They are not limited to electronic literature. They can also include video games, media art, and other digital forms.

Any of us who has had a floppy disk fail, a computer crash, a website disappear know that visceral media can also be fragile media. They’re reliant upon supporting hardware and software. It was a rude awakening to discover the 3 ½-inch diskettes I bought in 1995 were no longer readable three years later on the G3 iMac I was given to teach with because Apple no longer offered a floppy drive on that computer. My many CDs are today unreadable on my current iMac, a situation that actually began when Apple omitted the disk drive on its MacBook Air and Mac Mini earlier. Recognizing this problem I began collecting, along with electronic literature, the hardware and software needed to continue accessing my collection. The result is the development of the Electronic Literature Lab, or ELL, where I’ve amassed 47 computers covering every operating system and a robust collection of vintage software needed for accessing my collection. These are Macs, for the most part, dating back to 1977––and a few PCs running Windows 95 and 2000.

You may wonder at this juncture why I have been concerned about documenting this art. I mean, it’s one thing to keep 200 floppies and CDs from the late 1980s to the mid 2000s around, but another to commit one’s self––one’s research and resources––to saving them from extinction. But let me frame the problem this way: Only three poems of Sappho’s nine books are left to us due in part because the medium with which they were produced––papyri––is fragile and, so, rotted over time. Also contributing to their loss were better and easier writing technologies that were developed and implemented for disseminating literary art.

Bits also rot. Physical objects corrupt. Better and easier digital technologies have been developed and implemented for disseminating digital literary art since the introduction of floppy disks, CDs, Flash and a whole host of other abandonware. Like Sappho’s lyrical poetry, which spoke to the cultural output of 8th Century BCE, thousands of hypertext narratives and poems, kinetic poetry, animated text, interactive fiction, flash-based art, literary apps, and other forms of digital literature that speak to the experimental cultural output of the late 20th and early 21st century period will very soon no longer be available to the public. My lab staves this problem off––but only for a time. The general idea is to document as many works of electronic literature as I can before there are no parts left to fix my computers when they break and no back up software available for reading the works when my copies finally all fail.

[Part 2 and Conclusion followed but are not included.]