The paper below is taken from my presentation to be given at the British Library on Monday, April 4, 2016 at the Archival Uncertainties symposium. Following it are the four research questions I posed in relation to the challenges of archiving electronic literature.

————————

“The Electronic Literature Lab and the Pathfinders Project”

The Malloy Papers, Box 3

Introduction

In October 2015 I visited the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke University to conduct research into Uncle Roger, the first commercial work of electronic literature by pioneering artist Judy Malloy. There, among the 27 boxes comprising the Judy Malloy Papers, I sifted through notebooks, computer readouts of code of her works, images she took of her many works, correspondence with other artists, and exhibition papers. The materials associated with Uncle Roger were contained primarily in Box 3. At the time I was doing this work, I was researching four versions of Uncle Roger that Malloy had reported she had made between 1986 and 2012. Despite the fact that Uncle Roger was limited to one box and was organized in folders, it was still difficult to determine what constituted one of the

Uncle Roger, Version 1.0 as Topic 14 on The WELL

versions or where a version was located. Furthermore, one version––hand-made artists boxes with hand-designed inserts––were dispersed in different folders in the box, and the floppy disks themselves

were archived separately and, understandably, inaccessible for use. Unless someone knew exactly what she was looking for among the materials in the archive, she have not known that the item entitled, “Topic 14: A Party in Woodside, as first told on WELL, 1986 December,” represented Uncle Roger, Version 1.0, or know to look for four inserts for Version 3.3.

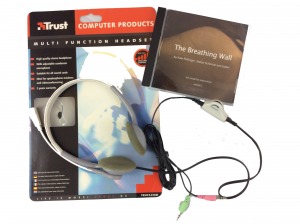

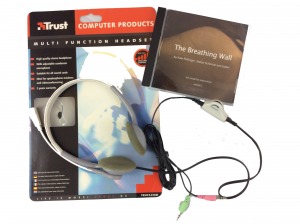

The Breathing Wall with its Headset

My experience with Uncle Roger is not unique. Electronic literature scholars can point to many examples of works where digital and analog materials are packaged together as “the work.” Some, like John McDaid’s Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse, include music cassettes. Kate Pullinger, Stefan Schemat, and Chris Joseph’s The Breathing Wall, for example, came packaged with a headset with a microphone along with a CD. Even web-based works like Amaranth Borsuk and Brad Bouse’s Between Page and Screen, may necessitate a print book. In light of current archival practices, how does one make such works available for study so that they retain their integrity? Herein lies the challenge.

I have attempted to address this challenge with the lab I have built for works of electronic literature at Washington State University Vancouver and the documentation I’ve been doing in that lab for these works. The lab is called Electronic Literature Lab, or “ELL,” and the documentation project is called Pathfinders.

[Here, I describe electronic literature and some of its recognizable features.]

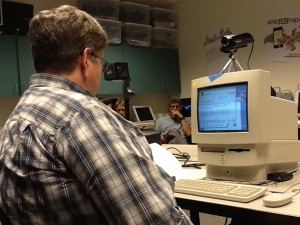

Electronic Literature Lab (ELL) at WSUV

ELL

I want to turn my attention now to a discussion of my lab. ELL consists of 45 vintage Macintosh computers and two PCs, all representing various operating systems and media affordances dating back to 1977. I own these computers and have collected them specifically to read electronic literature and document it for future generations.

ELL also consists of a personal library of over 200 works of e-lit. I began collecting it as I was a grad student in the early 1990s. As time passed, I became acutely aware that works produced a mere 20 years ago were quickly becoming forgotten and overlooked. After the introduction of the Apple iPhone in 2007 which eventually rendered works produced in Flash obsolete, I shared my collection through exhibits, which I have done at the Library of Congress in the U.S. and the Modern Language Association conferences in 2012, 2013, and 2014, among other venues. Information about the computers and works are available through an online catalog.

While preservationists make some e-lit works available via emulation and migration, something is indelibly lost in moving e-lit from its original source material into a new format. ELL, instead, follows the model of preservation called “collection,” by making it possible for scholars to study works on the

Bly’s Macintosh PowerBook 520

device on which they have been originally produced or for which they were originally accessed. In that regard, I own the laptop used by author Bill Bly to produce We Descend; I have a computer outfitted with Netscape Communicator so that scholars can read the full interactive version of Talan Memmot’s net masterpiece, Lexia to Perplexia.

The problem with ELL, like any specialized lab or library, is that few people get to visit it. This is one of the many archival uncertainties we face as scholars. I’m located in Vancouver WA, just across the Columbia River from Portland, OR. And though I get many visitors––scholars who want to do research in the lab––my location limits easy access to most people.

Pathfinders

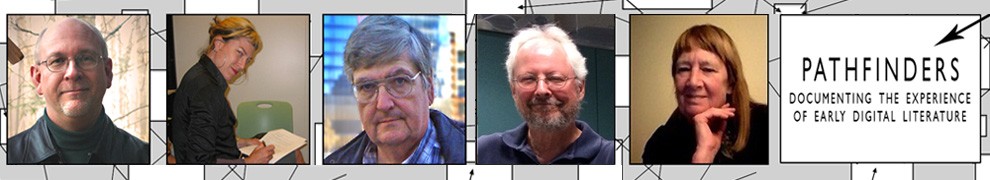

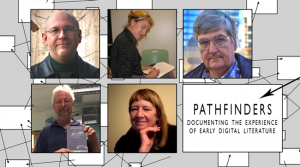

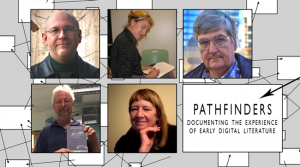

Enter Pathfinders, a project funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Office of Digital Humanities and led by my collaborator Stuart Moulthrop and me. In 2013 we harnessed ELL to document four seminal works of early digital literature: Judy Malloy’s Uncle Roger (1986-8), John McDaid’s Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse (1993), Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl (1995), and Bill Bly’s We Descend (1997). [I describe our project, which is outlined in detail on this blog site]

Enter Pathfinders, a project funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Office of Digital Humanities and led by my collaborator Stuart Moulthrop and me. In 2013 we harnessed ELL to document four seminal works of early digital literature: Judy Malloy’s Uncle Roger (1986-8), John McDaid’s Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse (1993), Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl (1995), and Bill Bly’s We Descend (1997). [I describe our project, which is outlined in detail on this blog site]

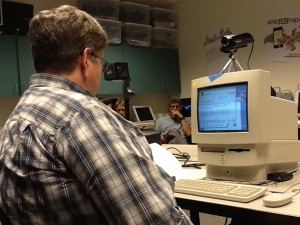

John McDaid giving a Traversal of Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse in ELL

The method innovated for documenting these is called the Traversal, which Stuart and I define as audio and video recordings of demonstrations performed on historically appropriate platforms. . . . The term is borrowed from Michael Joyce who used it in his essay, “Nonce Upon Some Times: Rereading Hypertext Fiction,” to refer to any particular reading of a hypertext (581). His use of the term was influenced by Espen Aarseth’s notion of the “traversal function” described in his book Cybertext [but . . . . ] for Stuart and me the Traversal always involves human agency, even though it may be strongly inflected by program logic or machine operations.

Our Traversals method requires the author and then two readers to perform the work, talking through choices they encounter. Passages are read aloud, hyperlinks are selected and announced, and experiences with the words and media elements are expressed. Stuart and I videotape the Traversals, photograph the floppy disks, the containers with which they were sold, and other materials in the package. In some cases we include sound files of works. We provide an ekphrasis of the liners of the jewel cases and the notes packaged along with the folios, providing detailed information such that if someone in the distant future wished to recreate the ephemera that accompany the work itself, he or she could with the information we provide. The result of our effort is a multimedia book published in June 2015 on the open source Scalar platform, containing 173 screens of content, including 53,857 words, 104 video clips, 204 color photos, and three audio files. To date we have had over 10000 scholars from close to 250 universities, centers, libraries, and schools.

At the Rubenstein with Pathfinders on my Laptop

What Pathfinders Means for the Literary Archival Experience

Imagine with me, if you will, another type of experience with the Judy Malloy Papers at the Rubenstein. This time the scholar is carrying her iPad or Android tablet and has accessed the section on Malloy at the Pathfinders book. She is interested in looking at Version 3.3 of Uncle Roger, so she opens Box 3. She knows from Pathfinders that she should probably study the materials in the folder marked “A Party in Woodside, Apple II version written in BASIC, 1987.” She also knows that she probably needs to look for the folder, “The Blue Notebook, Apple II+ version, written in BASIC, 1988,” and should also consult “Terminals, stand alone copy (disk removed),” as well as “Packaging, disk components” and “Packaging, disk versions, Apple II (disks removed).” In fact, any folder that alludes to a disk for an Apple computer is more than likely related to Uncle Roger, Versions 3.1 and 3.2. And because she cannot access the floppy disks, she can watch Pathfinder’s videos of Malloy traversing through a section of the work and hear the author talk about the production of all three parts of it in videotaped interviews with her. She can compare the materials she is examining in the boxes with the images of Version 3 used for the Pathfinders project. Doing so provides her with an understanding of the variances between the different artist boxes hand-made by Malloy, thus coming to see the level of material practice involved the digital production of this work.

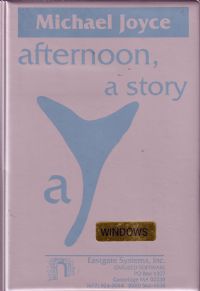

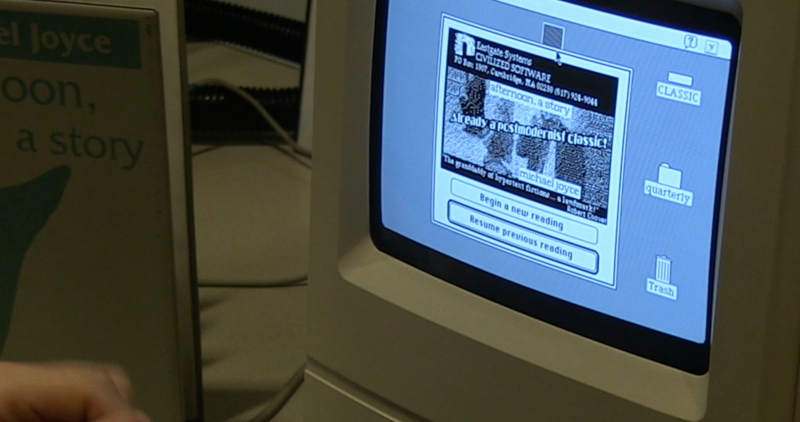

Stuart and I have begun Volume 2 of Pathfinders. In this volume we are documenting Michael Joyce’s afternoon: a story, collected at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. We are also documenting M.D. Coverley’s Califia and Stuart’s own Victory Garden––the archives of these works have yet to be collected. Since both of these works are inaccessible to readers due to technological obsolescence, the work that Stuart and I are undertaking with Pathfinders in ELL to make them available for study, even at the level we are doing, contributes to long term study of them.

Research Questions

My work with documenting electronic literature raises four important questions about digital preservation.

- For what kinds of digital objects is one approach to preservation more desirable than another?

I have been, for example, experimenting with preserving literary apps and have found that each new version of an app’s operating system can result in a new version of the work, or that the work itself is updated to fix bugs and include new and better features. It is not possible to save multiple versions on the same device because the new one wipes out the old. Thus, in order to preserve each version of an app, I have to have as many smart devices as updates––an expensive endeavor. Also beta versions I am sent to review are limited in terms of the time frame in which I get to access them. This limitation makes it impossible to compare the commercially published version with the beta or to collect betas for long-term study.

- How can differing approaches be combined or coordinated to best serve the interests of future scholars?

In the case of Judy Malloy’s Uncle Roger, the 1995 migrated web version (Version 5) and 2012 DOSBox emulated version (Version 6) both provide readers ongoing and ready access to the authorized version of the work. The latter especially attempts to recreate the visceral experience of interacting with a 1980s computer in that it simulates whirs and clicks of a 1980s computer. But it emulates the PC experience and not the Apple, on which the work was also read and experienced. The experience of ELL’s collection, however, adds to our knowledge of the work by providing the cultural context time-stamped as it is by the original hardware and software––with all of its unique features and quirks.

- What can researchers working on one sort of digital production (electronic literature, for instance) learn from those concerned with different but related areas (e.g., video games, digital writing more broadly conceived, or social-network discourse)?

I have been guiding students in my academic program (the CMDC Program at WSUV) with documenting video games with the Traversal method. One such project, Chronicles: Documenting the Articulation of Culture in Video Games by Madeleine Brookman, documents the iconic Japanese Role-Playing-Game, Chrono Trigger, released originally in 1972. This publication made an excellent case study for the application of the Traversal method to other media forms and showed that it does lend itself to documenting games. I see any form of media where sound, movement and interaction figure as part of its narrative strategy or poetics to benefit from our approach to documentation.

- How can researchers approaching the posterity of digital texts from diverse directions benefit from exchange of perspectives and results?

I think of this anecdote: A little over a month ago, I received an email message from Michael Joyce, author of afternoon: a story, considered one of the most important works of American e-lit today. It was published in 1990 on 3 ½-inch floppy disks and later migrated to CD technology. However, Apple computers running the El Capitan operating system cannot read the work. Curators of the Paraules Pixelades exhibit at the Art Santa Monica in Barcelona wanted to show afternoon but could not. Michael wanted to know if Stuart and I had produced a video of a Traversal of it. We had not. But within a week we produced one––James O’Sullivan, an e-lit scholar at University of Sheffield who was visiting ELL, served as a reader for a Traversal, which we videotaped. We were able to send the video to the curators, and the work could be exhibited as a documentary video. We fully understand that what the audience saw was not the work itself; but what they got to experience was a performance of it, and it allowed the work to live on to a new audience.

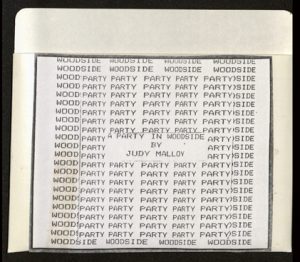

bugs in 3.1. Version 3.3 is the one that includes three floppies, each one containing one of the three episodes of Uncle Roger: “A Party in Woodside,” “The Blue Notebook,” and “Terminals.”

bugs in 3.1. Version 3.3 is the one that includes three floppies, each one containing one of the three episodes of Uncle Roger: “A Party in Woodside,” “The Blue Notebook,” and “Terminals.” Its sleeve differs widely from that produced for Version 3.3 we documented in Pathfinders in that rather than the entire sleeve being hand-made, only the label is. The label, 4 13/16” x 4 13/16”, is affixed to the front of the sleeve that the floppy had originally been packaged in. It is of the same paper type and texture––light copier paper––as that used for Version 3.3, so it stands out against the heavy card stock of the floppy disk’s original packaging.

Its sleeve differs widely from that produced for Version 3.3 we documented in Pathfinders in that rather than the entire sleeve being hand-made, only the label is. The label, 4 13/16” x 4 13/16”, is affixed to the front of the sleeve that the floppy had originally been packaged in. It is of the same paper type and texture––light copier paper––as that used for Version 3.3, so it stands out against the heavy card stock of the floppy disk’s original packaging.