The Pathfinders Team (sans Moulthrop) with John McDaid in the Electronic Literature Lab at WSUV

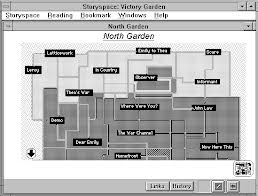

The Pathfinders team worked this week with John McDaid to preserve his work, Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse. Begun in 1986 as a challenge to write a novel that no one else could write, Uncle Buddy’s was expressed in hypermedia and published by Eastgate Systems in 1993. It constitutes the second work we have documented now––Stuart Moulthrop’s Victory Garden was the guinea pig that tested our theories and plans. While we recognized the importance of documenting these works for posterity, it was Uncle Buddy’s, a work out of print and impossible to find even used––that made us acutely aware of the historical implications of our efforts. The fact of the matter is, Pathfinders is about contributing to the future of literature through documenting its past––and the past we are documenting focuses on the digital literary experiments that emerged in the 1980s and has continued to grow and develop into what we call electronic literature today. We are, in effect, involved in creating the infrastructure for a literary history of electronic literature.

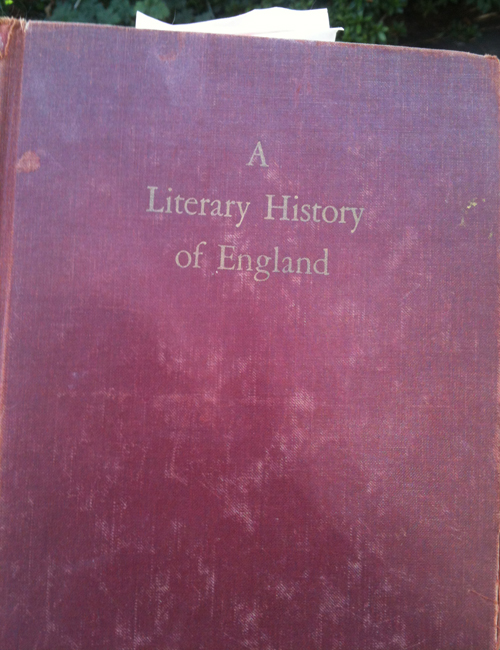

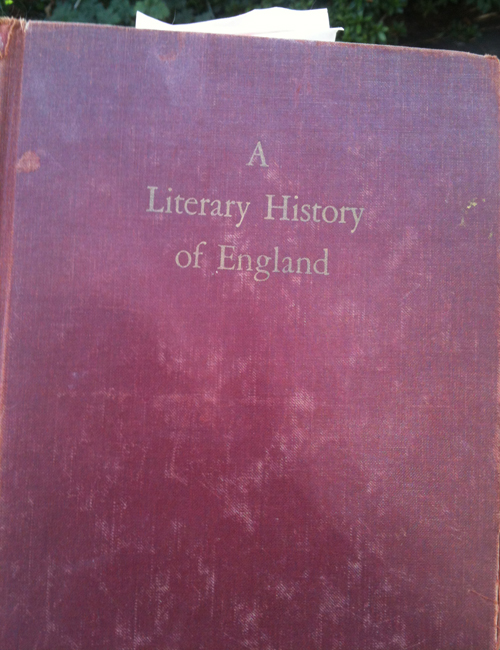

I have to admit that I love literary history and have, in my life, collected volumes of books about it. Baugh’s A Literary History of England, published in 1948, is a case in point. Close to 1700 pages, the book covers over a thousand years of English literary heritage, beginning with the middle ages. The copy I own was purchased second-hand well after I finished my undergraduate degrees in French and English and merely studying British literature for my own edification. I was delighted to find the previous author’s marginalia and underlined text, for they linked me to the book’s own history. At the first university where I held a tenure-track position, the PhD students in my department were required to know the literary history of England and America, in a strict chronology, for their exams. The department has long since revised this requirement, but during those early years of my career the “Baugh,” as I called it, served as a sort of bible for me because I was not an expert in British literature and needed to have at my disposal the information it contained between its covers. Keep in mind this was the mid 1990s when the browser was just introduced and the web still in its infancy. Books like the Baugh constituted the references we used for research.

I have to admit that I love literary history and have, in my life, collected volumes of books about it. Baugh’s A Literary History of England, published in 1948, is a case in point. Close to 1700 pages, the book covers over a thousand years of English literary heritage, beginning with the middle ages. The copy I own was purchased second-hand well after I finished my undergraduate degrees in French and English and merely studying British literature for my own edification. I was delighted to find the previous author’s marginalia and underlined text, for they linked me to the book’s own history. At the first university where I held a tenure-track position, the PhD students in my department were required to know the literary history of England and America, in a strict chronology, for their exams. The department has long since revised this requirement, but during those early years of my career the “Baugh,” as I called it, served as a sort of bible for me because I was not an expert in British literature and needed to have at my disposal the information it contained between its covers. Keep in mind this was the mid 1990s when the browser was just introduced and the web still in its infancy. Books like the Baugh constituted the references we used for research.

Eschew literary history all you want––and, yes, making grad students memorize historical “facts” found in them for their exams is a good reason to complain––but print literary scholars at least have a documented history to argue about or from. Those of us working in electronic literature should be so fortunate. We are working to construct ours, pixel by pixel, frame by frame, tag by tag. Making the task challenging is the fact that the works we seek to historicize are rendered obsolete sometimes seemingly overnight. The truth is, in order to have a history, one needs a stable present so that one can readily study the works one needs for that historicization. Pathfinders represents one of many efforts scholars in the U.S. and abroad are undertaking to document the heritage of electronic literature before it is too late.

I use the phrase, too late, not so lightly. During the panel presentation that I participated in at the 2013 Digital Humanities conference held in Lincoln, NE, an audience member asked the panelists how early electronic literature was received by the public when these works were first released. Two of us in the room (a man in the back of the room and me) of about 50 people could share with the audience the memory of picking up the slim folio (that contained the floppy disk and directions for how to install and interact with the work) of a hypertext novel in our hands and trying to figure out how to begin reading the work. The truth of the matter is that when that man and I are dead and gone from this world, it may very well be up to pure conjecture to figure out what people thought of these works when they were first released. We absolutely have no idea what people thought the first time they heard the Odyssey recited by the Homeric poet either, but we expect to have this gap of cultural history with a work written thousands of years ago when orality was the only mode for sharing one’s heritage. However, in an age when we have such such a wide variety of communication channels with which to express our views, not having a record of human experience with a cultural object produced a mere 20 years ago is a problem.

More challenging is that even if you got your hands on a copy of Uncle Buddy’s (doubtful, as I mentioned earlier, since it is currently out of print), you would need a Macintosh computer running the Classic operating system with the ability to read either floppies or a CD and loaded with Hypercard. Without it, you cannot do much except explore the contents of Uncle Buddy’s estate contained in the box with little idea of how the various items connect to the story.

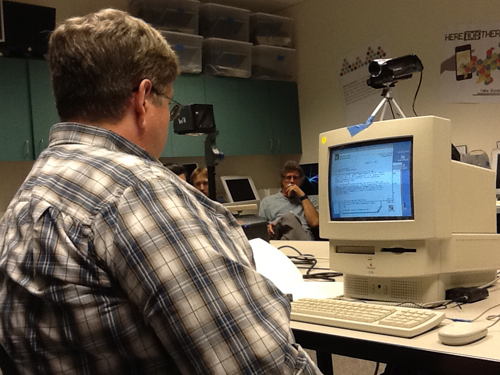

John McDaid giving his traversal of Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse

So, this week the Pathfinders team documented John McDaid’s Uncle Buddy’s Phantom Funhouse. McDaid was on hand to give a traversal; an in-depth interview about the works’ origins, its influences, and its challenges; and a public lecture. Two readers joined us to traverse the works themselves. Taken together, these activities should provide information that will help others to gain a better understanding of this particular work and the experiments that led to the development of electronic literature. We will post here at this website information about the work, including: 1) a complete inventory of the contents of his box (replete with photos of each), 2) a complete inventory of the media included in the work itself, and 3) a complete inventory of the art forms he experiments with in the work. The special video of John opening the box containing Uncle Buddy’s (what he said Mark Bernstein referred to as “the chocolate box of death”) and talking about each item and the part each plays in the story will also be made available.

So, I have a vision. Hear me out, and don’t laugh. One day, 70 years from now, literary scholars will argue about the 1700 pages (or screens or whatever the heck they call the presentational modality at that time) of electronic literary history that some future Baugh has painstakingly detailed. These scholars will exclaim that such labor is not necessary, will complain that such work is hegemonic, a master narrative in need of overhaul. In that imagined future, these scholars can well afford the luxury of rejecting literary history. But we can’t. Not today when we cannot even locate Uncle Buddy’s at our local library.