This post is derived from a part of the presentation I gave at the Electronic Literature Organization 2013 Conference in Paris, on September 26. The paper, which includes much additional information, will be submitted for publication. If you are interested in reading it now, please contact me.

—-

My second question focuses on obsolescence and the challenges it poses for presenting works in exhibits––what I refer to as the “challenge of presentation.”

Christiane Paul addresses this issue for media art in her seminal essay, “The Myth of Immateriality.” Here she reminds us that “the digital is embedded in various layers of commercial systems and technological industry that continuously define standards for the materialities of any kind of hardware components” (252) and suggests that the constant upgrades of hardware and software may be addressed, in varying degrees of practicalities, by collecting technologies (hardware and software) for the purpose of display, emulating code on newer systems, and migrating works to the next version (269). We can extrapolate much from her ideas, but Paul’s view that the “lowest common denominator for defining new media art” is “its computability” (253) bears attention in that it signals a difference in aesthetics between media art and electronic literature and explains why she values one strategy (emulators) over others (collecting and migration).

Unlike media art where “media” is anchored in the tradition of cinema and “art” is associated with terminologies found in fine art and performance, electronic literature generates from a wide variety of disciplines and practices, among them digital humanities, which itself is described as a “mode of scholarship and institutional units for collaborative, transdisciplinary, and computationally engaged research, teaching, and dissemination” (Burdick et al 122). Additionally, electronic literature embraces the technological origins of both coding and writing technologies, declaring this heritage in its genres’ naming convention. Computability––functions made manifest by characters expressed in written code and which drives the words, images, video, animation, sounds, etc., of the work is the point––is the common denominator connecting hypertext fiction with flash poetry, generative poetry with interactive fiction. So, what is the best way to present electronic literary works produced on systems that have been rendered obsolete?

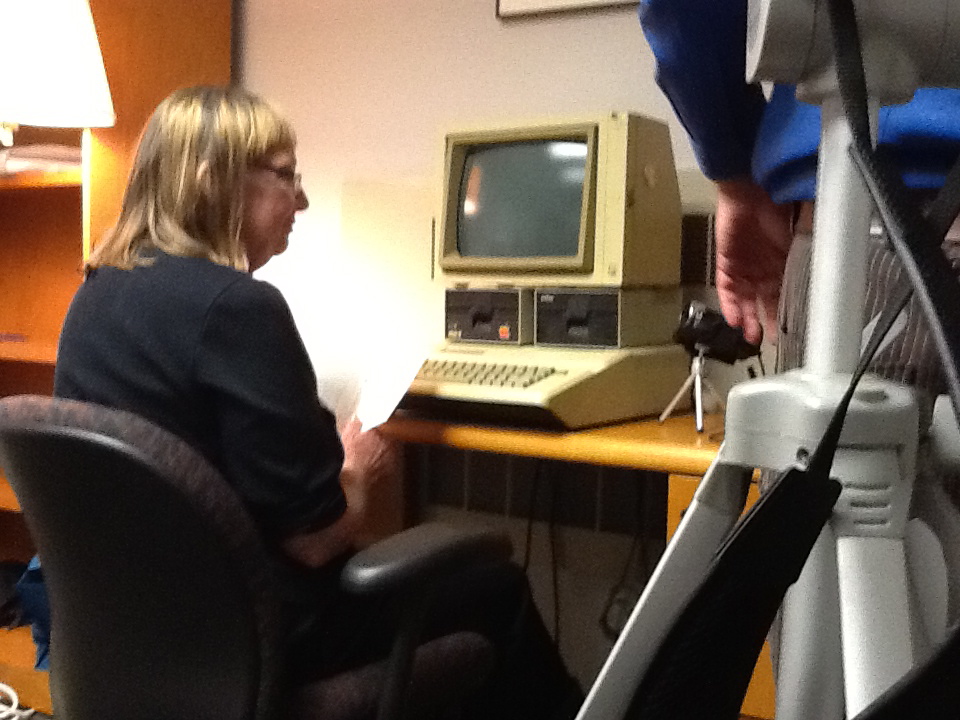

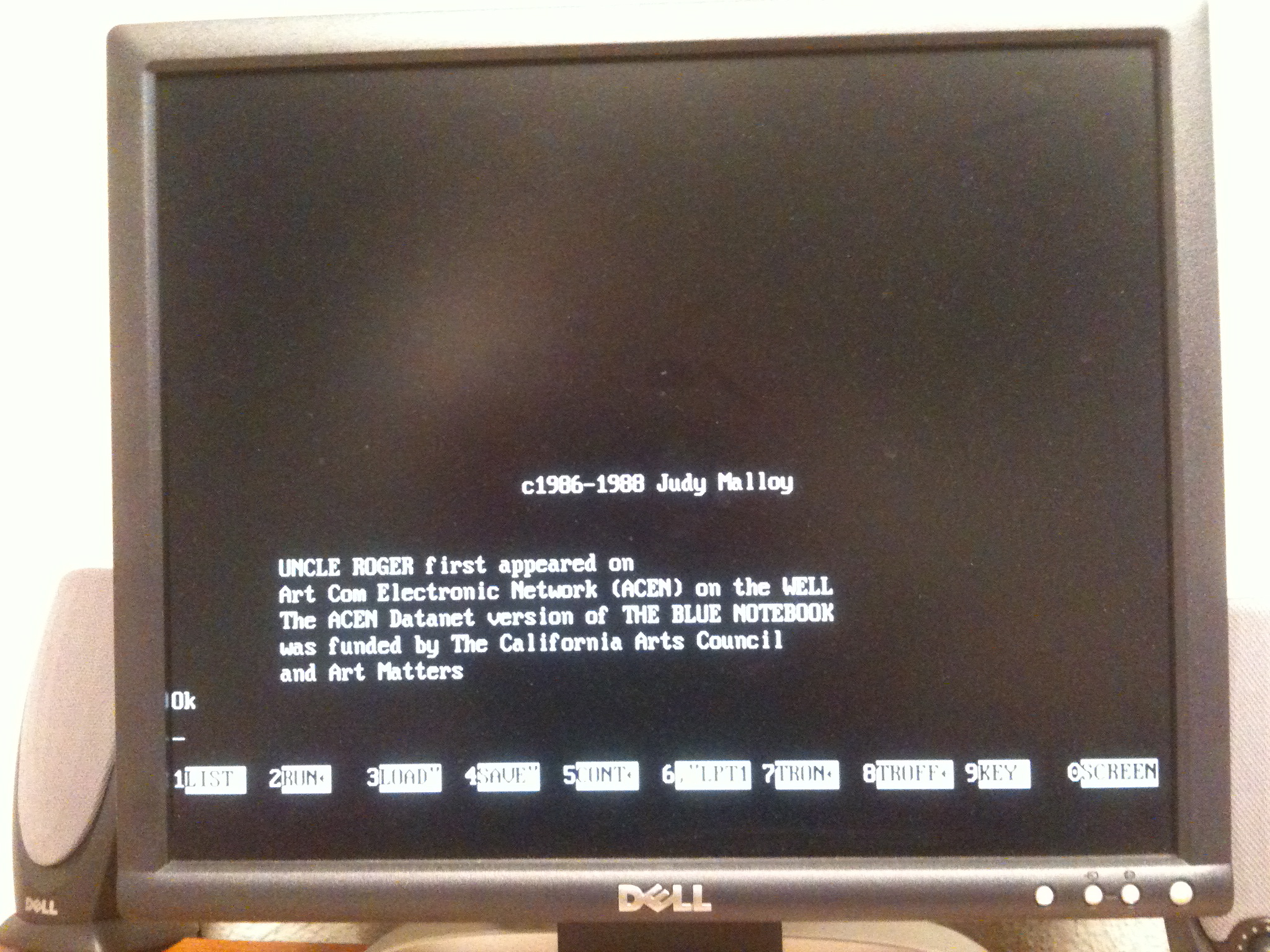

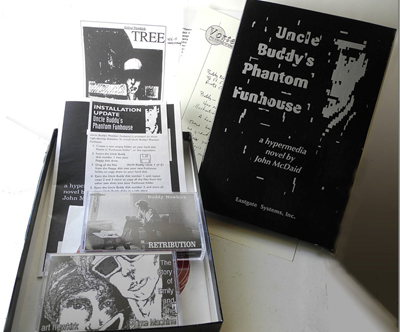

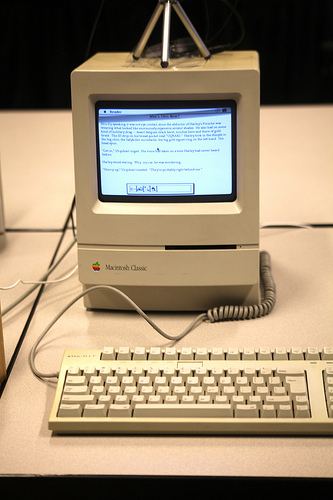

To answer this question, I turn to Judy Malloy’s database narrative, Uncle Roger, begun in 1986 and published on the ArtCom Electronic Network located in the WELL (“Whole Earth ‘Lectric Link”) in 1987. It was contemporary with the Apple IIE and was, in fact, produced on this model. Version 1.0 was originally written in BASIC and delivered as a serial novel comprised of 100 lexias over the network.

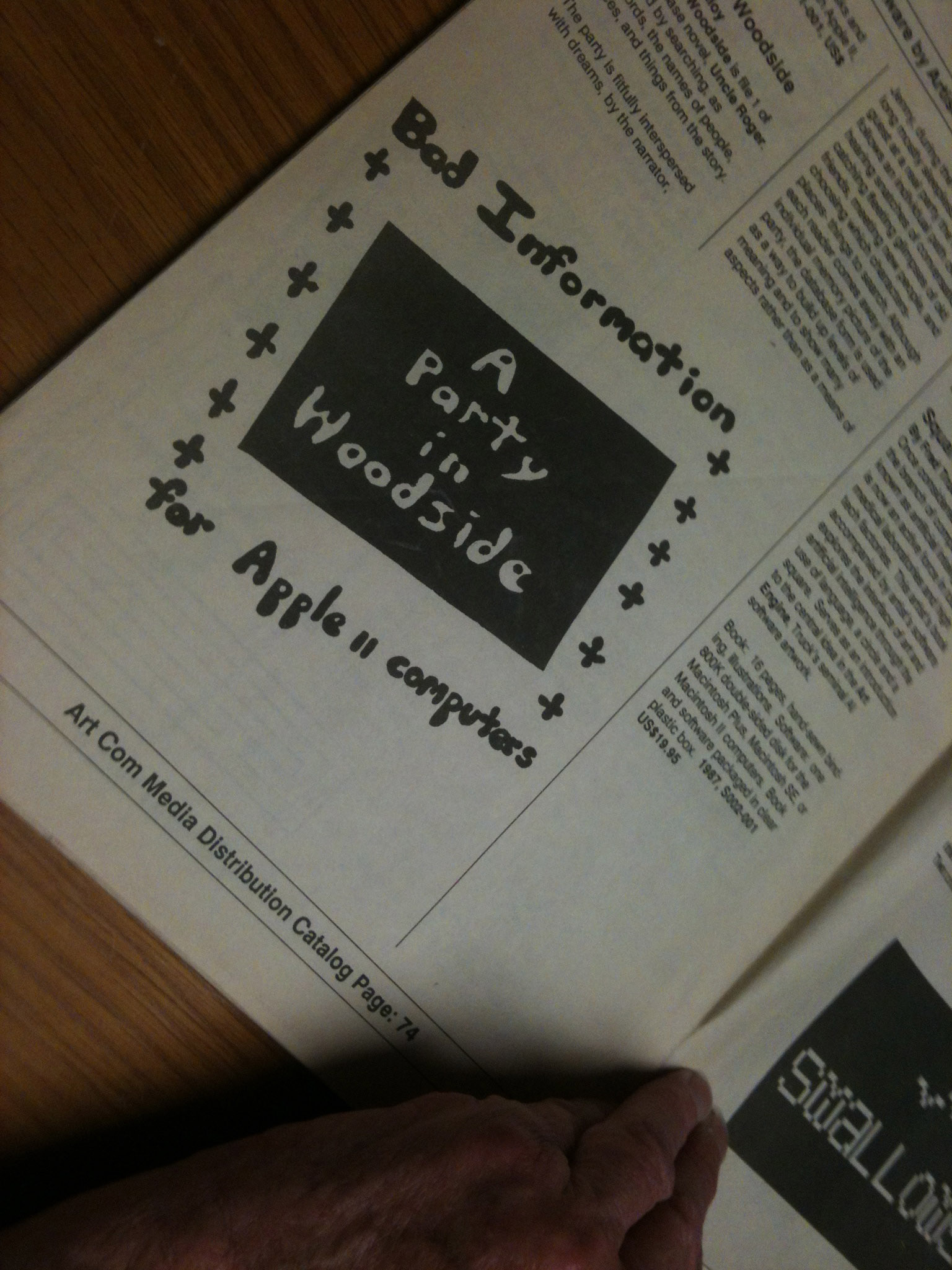

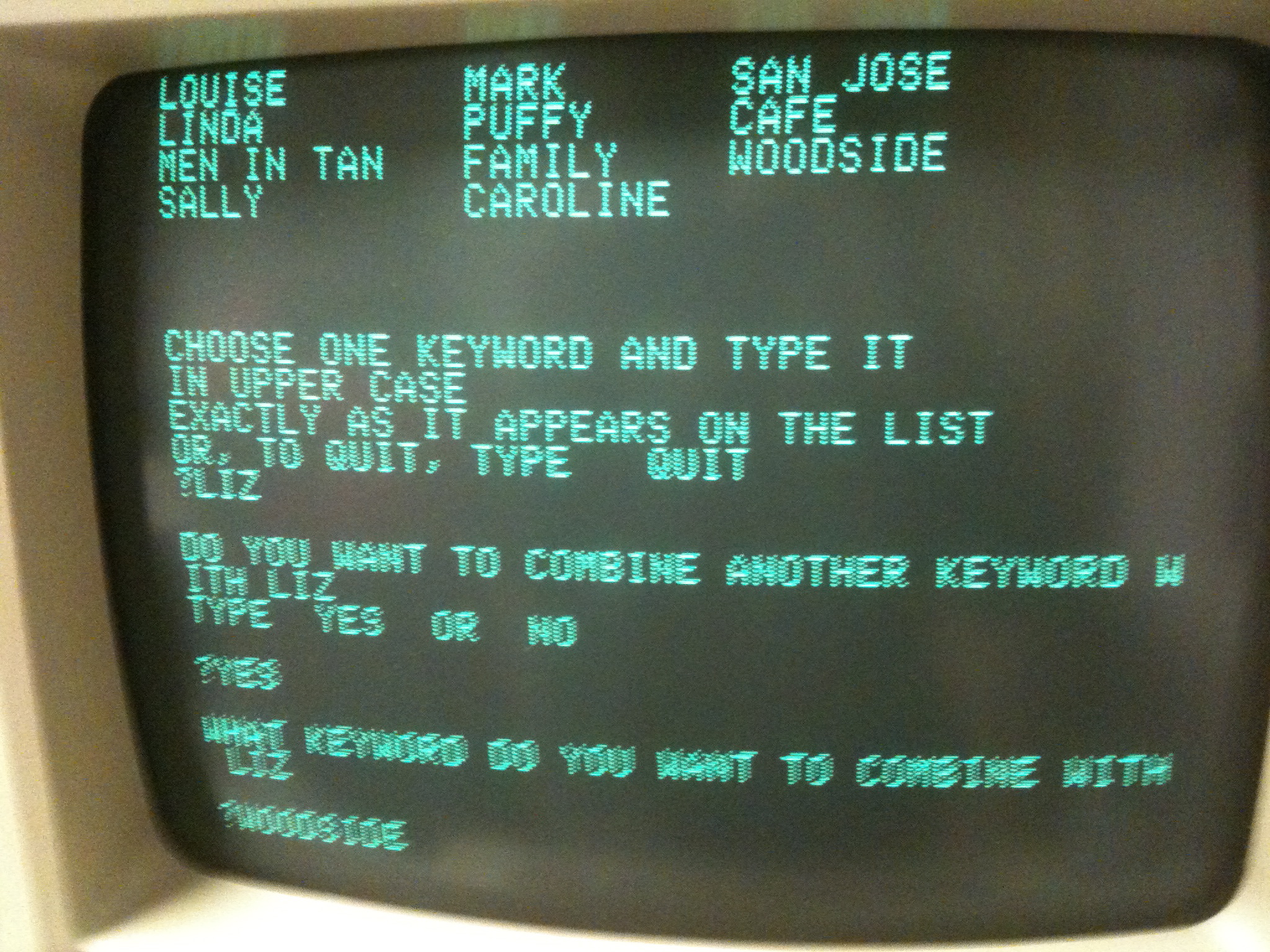

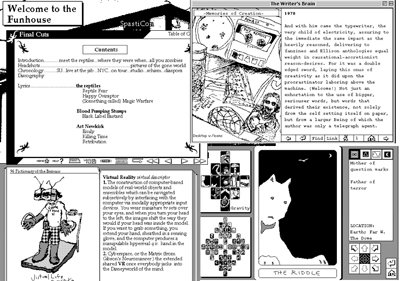

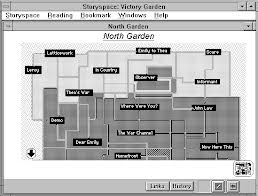

The version that was eventually sold commercially through the ArtCom catalog, however, was Version 2.0. It was made up of three 5 ¼ floppy disks on which Judy organized the material from 100 lexias of the previous version into three parts: “A Party at Woodside,” “The Blue Notebook,” and “Terminals.” Version 2.0 made it possible for readers to navigate the story by selecting and typing keywords on the command line. Each combination would result in a lexia or series of lexias relating to the keywords typed. Typing “David” followed by “Jenny” in the next query, for example, brings up episodes about the relationship between these two people: David’s messy apartment that Jenny recalls, the picture of David’s former lover that Jenny tears into tiny pieces and places back into his wallet.

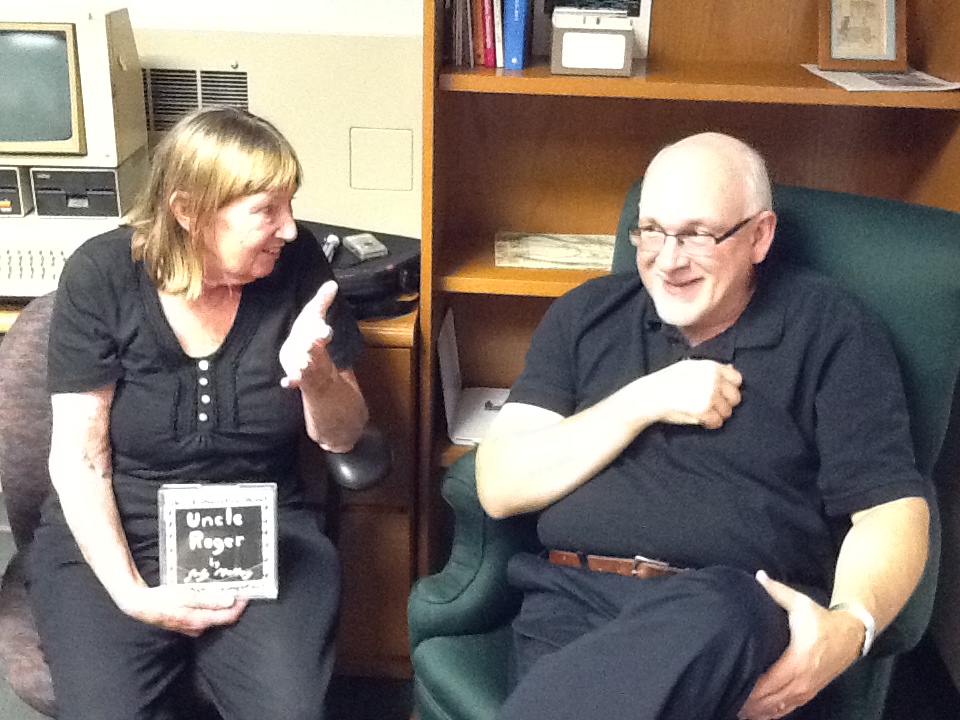

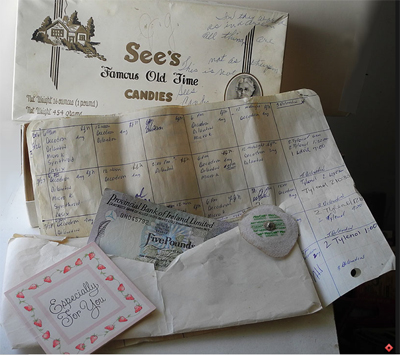

Judy sold Version 2.0 from her home as a hand-made artist package. As far as she knows (Malloy, “Interview”), only three copies of the complete work exists: two that she donated to Duke University along with other materials that now comprise the Judy Malloy Collection, and one divided, at the moment, between Judy and me. So, to present all these parts of this historically important work in the Pathfinders exhibit in at the Modern Language Association conference in Chicago, IL in January, I need to ask Judy to lend me the floppy I am missing (“Terminals”), then, ship my Apple IIE to Chicago in order to show them. Recognizing these two constraints would limit her readership, Judy did produce an online version in 2012, Version 3.0, that runs on contemporary computers. [1]

Having access to Uncle Roger online sounds like a good solution to the problem of shipping a vintage computer across the U.S. and risking a rare work of electronic literature, but let’s step back for a moment and think about the qualities that may be lost if I blithely show Version 2.0 on any Apple IIE or Version 3.0 on a contemporary computer without thinking critically in advance about my choices.

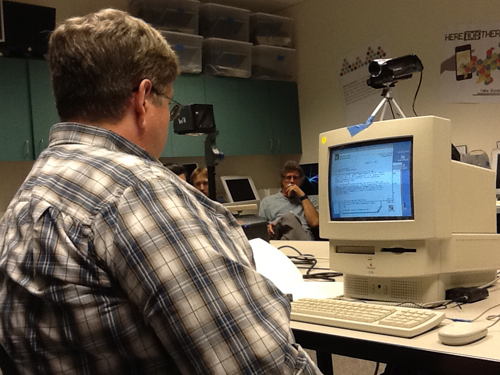

Uncle Roger centers on the semi-conductor chip industry of Silicon Valley of the 1980s, a time in which floppy disks and an Apple IIE computer with its black screen and green dot matrix type were familiar technologies. This particular computer is one of the most robust that Apple ever produced, lasting 11 years on the market. When Judy began posting Uncle Roger on the WELL, the computer was only three years old. In fact, Judy wrote Uncle Roger on a version of the Apple IIE that constrained her lines to 50 characters, resulting in a narrative poem and Judy finding herself a narrative poet. Later iterations of the computer cause the lines to wrap in ways Judy did not plan for them to, but Version 3.0 running on a contemporary computer keeps the line lengths in tact. What is lost in moving to the newer version, however, is the look and feel of the period––the cultural context of the work itself. On the circa 1988 Apple monitor, the aesthetic of computer and story design meet seamlessly, the time-stamp of the work’s technology making sense in the context of the material presence of the computer. Thus, in showing Uncle Roger at the Pathfinders exhibit at the MLA where over 5000 literary scholars convene, I need to be aware that I am doing more than showing content of a work––I am also providing a context for understanding and interpreting the work.

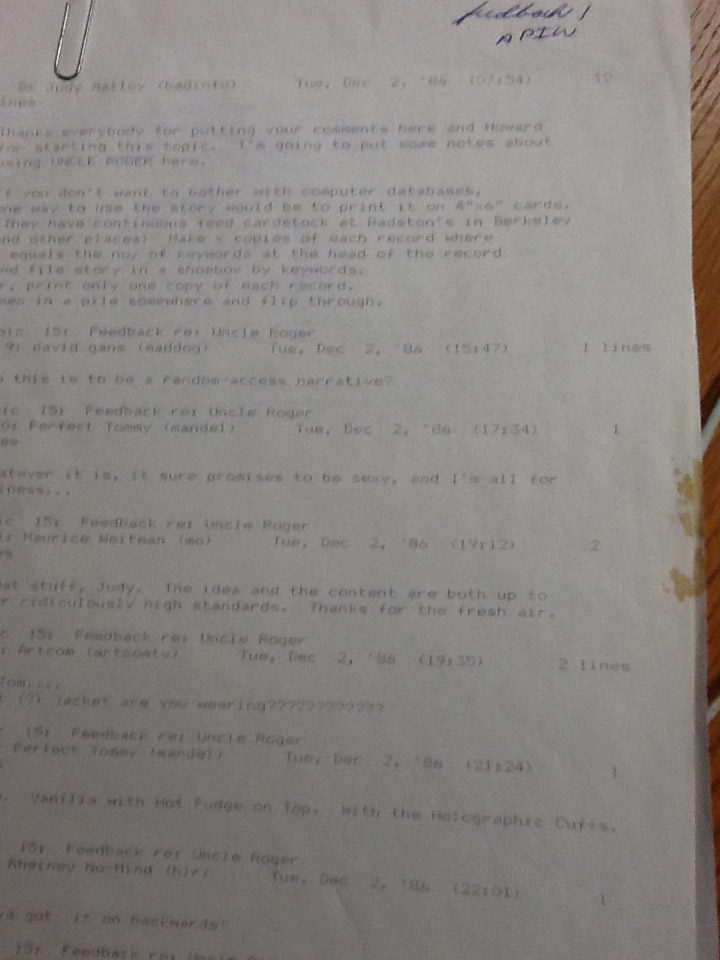

Additionally, as curator I am taxed with highlighting the unique features of Uncle Roger, such as its interactivity and ability to compel audience participation. In fact, the work may very well be one of the first social media narratives, presaging twitterature and other familiar contemporary forms today. With Version 1.0 Judy posted one to two lexias every day, in serial style, to friends in her network, who then responded by chatting with her about the story and riffing off to other topics. “Great stuff, Judy,” one reader wrote on December 2, “the ideas and the content are both up to ridiculously high standards. Thanks for the fresh air.” Another: “What jacket are you wearing?” (Malloy, ArtCom). This means that readers of both Versions 2.0 and 3.0 are missing a crucial feature of the work found in Version 1.0.

Translation theory holds that translation is ultimately a betrayal of the text by the translator. Tautologically speaking, the best we can do to bring a work to a reader is just our best (Biguenet and Schulte). So, for the Pathfinders exhibit, I will be carting my Apple IIE computer to Chicago since it wraps Judy’s text properly and, so, provides a better cultural context for the work than the Mac Minis or iMacs I generally use for exhibits does. I will also provide examples of the conversations that took place at ArtCom between Judy and her audience, materials Judy has allowed me to photograph for my research.

Notes:

[1] A more complete history of Uncle Roger can be found at Judy Malloy’s Authoring Software, http://www.well.com/user/jmalloy/uncleroger/uncle_readme.html.

Works Cited:

Biguenet, John and Reiner Schulte. The Craft of Translation. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Burdick, Anne, Johanna Drucker, Peter Lunenfeld, Todd Presner, and Jeffrey Schnapp. Digital_Humanities. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2013.

Grigar, Dene and Stuart Moulthrop. “Exhibit.” Pathfinders: 25 Years of Experimental Literary Art. 15 Sept. 2013. http://dtc-wsuv.org/wp/pathfinders/exhibit.

Malloy, Judy. “Interview for Pathfinders.” Dene Grigar and Stuart Moulthrop. 8 Sept. 2013.

—. Uncle Roger. ArtCom Electronic Network. 1987.

Paul, Christiane. “The Myth of Immateriality: Presenting and Preserving New Media.” MediaArtHistories. Ed. Oliver Grau. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2007. 251-274.